1. Name and location of the property: The property known as the W.P.A. / Douglas Airport Hangar is located at 4108 Airport Drive in Charlotte, N.C.

1. Name and location of the property: The property known as the W.P.A. / Douglas Airport Hangar is located at 4108 Airport Drive in Charlotte, N.C.

2. Name, address and telephone number of the present owner of the property: The owner of the property is:

City of Charlotte

600 E. 4th Street

Charlotte, NC 28202-2816

Telephone: 704-336-2241

3. Representative photographs of the property: This report contains representative photographs of the property.

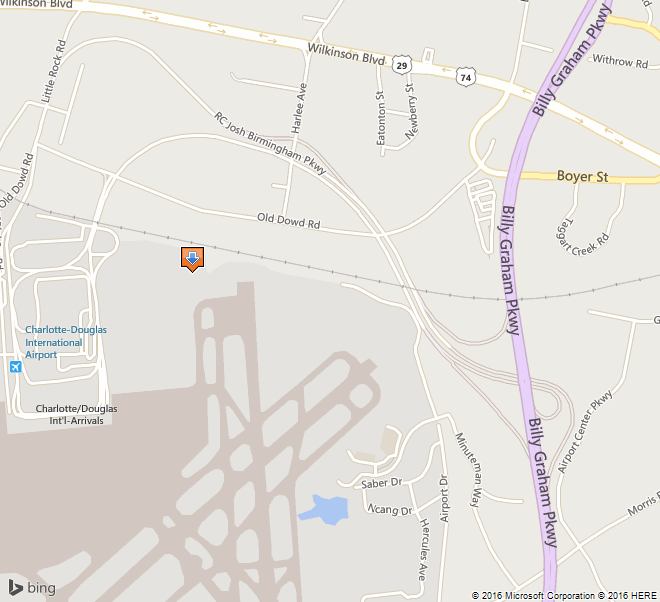

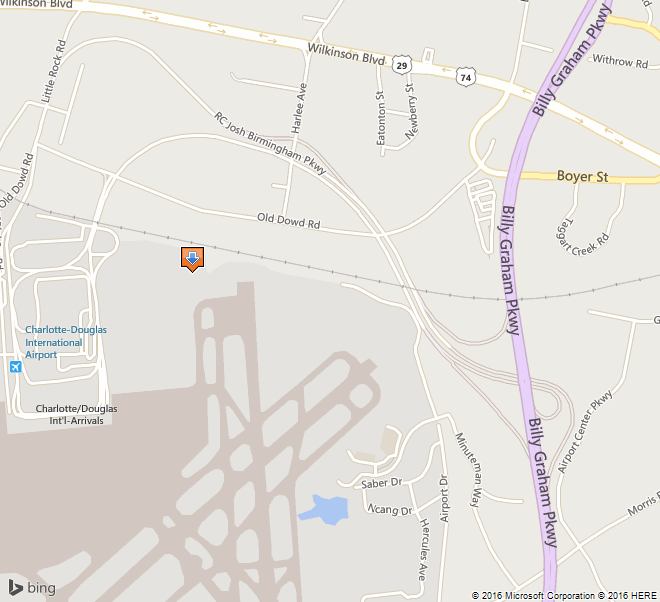

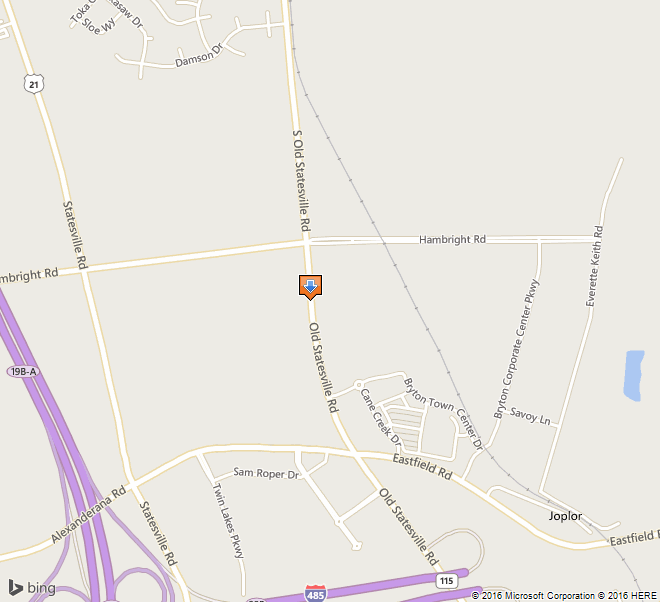

4. A map depicting the location of the property: This report contains a map depicting the location of the property. The UTM coordinates are 17.506000.3905000.

5. Current Deed Book Reference to the property: The writer of this report was unable to find the most recent deeds to this property. The tax-parcel ID is 11522102a-005.

6. A brief historical sketch of the property: This report contains a brief historical sketch of the property prepared by Ryan L. Sumner.

7. A brief architectural description of the property: This report contains a brief physical description of the property prepared by Ryan L. Sumner.

8. Documentation of how and in what ways the property meets the criteria for designation set forth in N.C.G.S. 160A-400.5:

a. Special significance in terms of its historical, prehistorical, architectural, or cultural importance: The Commission judges that the property known as the W.P.A. / Douglas Airport Hangar does possess special significance in terms of Charlotte-Mecklenburg. The Commission bases its judgment on the following considerations:

1.) The Hangar, erected in 1936—1937 by the Works Progress Administration, was intimately tied to a federal work program that preserved Charlotteans’ skills and self-respect during a period of massive unemployment.

2.) This airport was the W.P.A.’s largest project, in allotment of funds, at the time in North Carolina.

3.) Of the original five structures built by the W.P.A. at the airport, only the hangar is extant.

4.) The establishment of the airport contributed greatly to physical and economic development of the city, ever expanding to supply comprehensive and convenient air transport to Charlotte.

b. Integrity of design, setting, workmanship, materials, feeling, and/or association: The Commission contends that the physical description by Ryan L. Sumner, which is included in this report, demonstrates that the essential form of the W.P.A. / Douglas Airport Hangar meets this criterion.

9. Ad Valorem Tax Appraisal: The Commission is aware that designation would allow the owner to apply for an automatic deferral of 50% of the Ad Valorem taxes on all or any portion of the property that becomes a “historic landmark.” The current appraised value of the 502.52 acres of land is $32,834,660. There are multiple improvements on this parcel—the current appraised value of the Hangar is $82,090, while the total improvements are valued at $147,437,660. The total current appraised value is $180,272,320. The property is zoned I-1and I-2.

10. Portion of the Property Recommended For Designation: The interior and exterior of the building and a sufficient amount of land to protect its immediate setting.

Date of Preparation of this Report: May 15, 2002

Prepared by: Ryan L. Sumner

Assistant Curator

Levine Museum of the New South

200 E 7TH St.

Charlotte, NC 28202

Telephone: 70.333.1887 x226

Historical Background Statement

Ryan L. Sumner

April 25, 2002

Summary Paragraph:

The W.P.A. / Douglas Airport Hangar (“the hangar”), erected in 1936—1937 by the Works Progress Administration, was tied to a federal work program that preserved Charlotteans’ skills and self-respect during the Great Depression. Of the original structures built by the W.P.A. at the airport, only the hangar is extant. During the Second World War, when the airport was dominated by Morris Field, the hangar serviced and stored planes for the civilian flights in and out of Charlotte. As the economy grew in the post-war years, so did the airport, which built bigger and more modern repair facilities. The hangar was leased to small chartered flight organizations until the mid-1980s when it was abandoned and fell into disrepair. The building of the airport contributed greatly to physical development of the city, expanding throughout its history to serve the air transport needs of the city.

Context and Historical Background Statement

Prior to the building of Douglas Airport, flights in and out of Charlotte were rare. The Queen City’s only airfield was Charlotte Airport (later known a Cannon airport), a small private venture operated by Johnny Crowell, a famed Charlotte aviator. Although this landing strip was christened amid much fanfare as an airmail stop on April 1, 1930,1 with passenger service from Eastern Air Transport (later Eastern Airlines) following a few months later, the field was only open on weekends, for air shows, and war-pilot training.

For Charlotte Mayor Ben E. Douglas, this inadequate air operation did not fit his vision for Charlotte, which could not grow “without water and transportation.”2 In an era when commercial flight was relatively new, Douglas continually pushed for a major municipal airport to serve the area.3 Douglas convinced prominent Charlotteans of the necessity of an airport, gradually building up a base of support. In the summer of 1935, the Chamber of Commerce appealed to the City Council to provide adequate passenger and airmail service to and from the city.4

On September 3, 1935, Mayor Douglas led the Charlotte City Council in authorizing the City Manager to file an application with the Works Progress Administration for funding to build an airport.5 The application was approved and on November 13, 1935, the council voted to divert funds in order to facilitate the purchase of land for the airport site and to repay the transfers upon the sale of airport bonds.6 The bonds were sold on March 1, 1936.7

The Works Progress Administration (W.P.A.), created by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1935, is considered the most important New Deal work-relief agency. The W.P.A. developed programs to create work during the massive national unemployment and economic devastation created by the Depression. From 1935 to 1943, the W.P.A. provided approximately eight million jobs at a cost of more than eleven billion dollars and funded the construction of hundreds of thousands of public buildings and facilities. By the end of 1939, 125,000 North Carolinians who were “caught between the grindstones of a maladjusted economy” had sought gainful employment from the state’s 3984 Works Progress Administration projects.8

FDR visiting Charlotte, September 1936

From the National Archives and Records Administration

Groundbreaking, 1935

From Charlotte / Douglas International Airport Archives

Construction began in December 1935 under the direction of N.C. W.P.A. director George Coan and John Grice, Charlotte Regional W.P.A. Director.9 Hundreds of unemployed men, bundled in overcoats, stood in line for the first W.P.A. jobs, which consisted of clearing the site of trees and underbrush. One hundred and fifty of those men found work on the airport the first day.10 Many of those present had no means of transportation and walked six or more miles to the airport site.11 The Charlotte airport project grew into the W.P.A.’s largest project, in allotted funds, until that point; W.P.A. funds accounted for $323,889.47, which were combined with an investment by the City of Charlotte $57,703.28. Of this money, $143,334.96 was paid in salary to the workers on the site.

When W.P.A. construction ceased in June 1937, the new Charlotte Municipal Airport boasted an administration/terminal building, a single hangar, beacon tower, and three runways—two 3000 feet-long landing strips and one 2,500 strip, each 150 feet wide.12 The following year, the U.S. Department of Commerce added a “Visual-type Airway Radio-beam” system and a control building, which allowed pilots to engage in blind flying and blind landing.13 Of these structures, only the Hangar remains.

The City Council wasted no time putting the new airport to use. They appointed an airport commission, chaired by William States Lee, Jr. to operate the new facility. Eastern Airlines flew the first plane into the new airport on May 17. Six daily flights took off from Charlotte Municipal Airport in its first year of operation; by 1938, the number of flights increased to eight. In 1940, the city officially dedicated the site, “Douglas Municipal,” in honor of the mayor who spearheaded the movement to built the airport.

The Recently Completed Municipal Airport

Collection of the Levine Museum of the New South

North Carolina Aviator, 1935

Collection of Piedmont Airlines Historical Society

Douglas Airport saw significant expansion by the federal government beginning in 1941, when the City of Charlotte leased the airport to the War Department for an indefinite period for a nominal fee.14 Between January and April of that year, the Army Air Corps oversaw the construction of Charlotte Air Base, a military installation built to the south of the Douglas Municipal site, adjoining the runways. The military acquired additional land for the project, lengthened and widened the runways; they built a huge hangar-repair facility, a hospital, reservoir, shops, barracks, and over ninety other structures.15 The air base was renamed Morris Field, shortly after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. In May 1946, the War Assets Corporation conveyed the property back to the City of Charlotte, after investing more than five million dollars in the site.

Female workers repair a plane at Morris Field during WWII

Carolinas Historic Aviation Commission

Contrary to what some Charlotte historians have written, commercial air travel did not cease during the Charlotte Air Base or Morris Field days. Civilian passengers continued to emplane from the municipally operated terminal with little reduction in daily flights.16 The hangar built by the W.P.A. steadfastly serviced and sheltered civilian planes throughout the war.

New Terminal designed by Walter Hook, dedicated 1954

Collection of Levine Museum of the New South

In the prosperous days following World War II, the airport commission began to work on a new terminal for the epicenter of the “Sun-belt Boom.” Scheduled airline service increased rapidly from eight flights per day in 1939, to thirty flights per day in 1949.17 The new terminal, built from concrete, steel, glass and brick, epitomized the modern movement that was sweeping the country at that time. The original terminal, with its stucco walls and tin roof, didn’t fit this new paradigm; it was torn down about 1968.18

Modern hangars and repair facilities accompanied the airport expansions of the fifties and 1980s, relegating the hangar built by the W.P.A. to second-class status. The airport began to use the hangar for “fixed base operations,” and leased it to small outfits that chartered private planes for flight training and cargo transport. The hangar’s last tenant was Southeast Airmotive, which vacated the building in 1985.

The Hangar while leased by Southern Airmotive, c. 1980s

From the Charlotte Observer

As a result of neglect and Hurricane Hugo, Charlotte’s last original airport building had fallen into a state of great disrepair by the early 1990s. Nearly all the windows were smashed and the doors damaged. The structure was overgrown with kudzu. The hangar was filled with several years worth of scrap and general aviation junk, while a thirty-foot mound of hurricane-related debris was piled against the outside. The Airport slated the building to be razed.19

Aviation historian Floyd Wilson met with Airport Director Jerry Orr, and convinced him to spare the building and allow it to be turned into a museum. In 1991, Wilson formed the Carolinas Historic Aviation Commission (CHAC) and held several successful fund-raisers to restore the hangar.20 Under Orr’s direction, the airport provided a security fence, replaced the broken glass, sandblasted and repainted the walls, and repaired the doors to working order.21 Today CHAC operates the facility as the Carolinas Aviation Museum, displaying a wide variety of aircraft, plus military and aviation-oriented memorabilia.

The growth of Charlotte/Douglas International Airport and the growth of the Charlotte Region are tied closely together. The airport links Charlotte with markets in the United States and around the world – an important factor in today’s global economy. According to a 1997 report by the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute, the airport contributes nearly four billion dollars in annual total economic impact to the Charlotte region, providing 71,392 jobs to workers who earn $1.968 billion in wages and salaries.22

Brief Architectural Description

Ryan L. Sumner

April 25, 2002

Location Description:

The W.P.A. / Douglas Airport Hangar is situated in the northeast corner of the Charlotte/Douglas International Airport property in southwest Mecklenburg County. The rear elevation of the structure faces northward and overlooks a steep slope down toward Airport Road and the Norfolk Southern Railroad (formerly Southern Railroad) line, which lies approximately one hundred meters behind the structure. The hangar lies one thousand meters south of Wilkinson Boulevard, the only four-lane highway in the Carolinas at the time of the airport’s construction.23 Charlotte Mayor Ben Douglas chose this site because of its proximity to the rail line, and Wilkinson Boulevard, since in 1936 pilots navigated largely by visual reference to ground landmarks.24

To the west of the hangar, the land is generally flat, grassy, and empty. None of the other structures that stood on the western side of the Hangar is extant. Immediately west of the hangar stood Charlotte Streetcar #85, which was moved to the airport following the close of the trolley line in 1938 and was converted into an office for the Air National Guard; it was removed in the 1940’s.25 Slightly farther west stood the seventy-five feet tall radio beacon tower. The airport’s administration / terminal building sat atop a now leveled slope a few yards east.

The hangar’s front visage faces south over a flat open asphalt apron (approximately twice the size of the hangar) and over the modern runways of Charlotte/ Douglas International Airport. The roar of airplanes taking off and landing in close proximity drown out conversations and fittingly dominate the space

The area east of the hangar is a continuation of the asphalted area that lies in front of the structure and is currently used as a parking lot. A non-extant runway lighting system stood on the east side of the hangar.

Structural Description:

The W.P.A. / Douglas Airport Hangar is a one story, one hundred feet wide by one hundred feet deep, by thirty feet tall, metal structure. It is typical of aviation hangars built by the Works Progress Administration (later known as the Works Projects Administration), which utilized stock plans and worked on 11 airport projects in North Carolina before 1940.26

The exterior structure has a gable roof with rounded cornices composed of prefabricated sheet metal with a pressed corrugated pattern. The exterior roof is covered with weatherproofing tar and painted silver.

The rear north-facing side of the hangar is largely composed of like materials and is punctuated by six bays of window groups. Each window group on the rear consists of a central section of fifteen panes arranged in three horizontal rows of five. On either side of each large section is a smaller group of nine panes arranged in three horizontal rows of three. The higher two-thirds of each small section are hinged at the top and can be pushed outward and propped open for ventilation. “CAROLINAS AVIATION MUSEUM” has been recently painted across the rear wall of the structure, but underneath this new sign, it is possible to read “DOUGLAS AIRPORT CHARLOTTE N.C.”

The front south-facing side is characterized by ten bays of doors that are approximately 22 feet high and ten feet across; each is punctuated with a window grouping of two sets of nine panes arranged three panes wide by three panes high. These ten doors constitute the central entrance and slide left or right along five tracks—closing the hangar completely, or creating a maximum opening of eighty feet. “CAROLINAS AVIATION MUSEUM” has recently been painted across the structure’s front above the door, and an Esso sign has been mounted near the roofline, just below a windsock mounted upon the roof.

The exterior of the hangar retains a very high level of integrity. The east and west walls have no windows and are composed of same material as the roof, but with a tighter corrugation pattern. A small addition to the west side and a larger addition to the east side were constructed sometime after the original construction. The small addition is approximately ten feet high, nine feet wide, and eighteen feet deep; it is composed of cinder blocks and wood, with a shed roof. The large addition on the west side is similarly composed of white cinder block with a shed roof, but is seventeen feet high, twenty feet wide, and one hundred twenty feet deep.

The interior of the hangar is completely open from floor to vaulted ceiling. The roof and walls are totally supported by a steel frame skeleton that consists of six I-beam tented arches, which transverse the structure from east to west. The floor is poured cement, and the interior walls are merely the reverse sides of the sheet metal used for the exterior walls.

Endnotes:

1. Charlotte Observer, (April 2, 1930), p1.; Charlotte Observer, (December 11, 1930); Blythe, LeGette and Charles Brockman, Hornet’s Nest: The Story of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County, (Charlotte, NC: Heritage Printers, 1961), p265-6

2. Carter, Gary, “Ben Douglas, Sr.: Charlotte’s Former Mayor Lives in a Future of His Own Creation,” Clippings Folder, Ben E. Douglas Papers, Robinson-Spangler Carolina Room, Public Library of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County.

3. Carter, Gary, “Ben Douglas, Sr.: Charlotte’s Former Mayor Lives in a Future of His Own Creation,” Clippings Folder, Ben E. Douglas Papers, Robinson-Spangler Carolina Room, Public Library of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County.

4. Carter, Gary, “Ben Douglas, Sr.: Charlotte’s Former Mayor Lives in a Future of His Own Creation,” Clippings Folder, Ben E. Douglas Papers, Robinson-Spangler Carolina Room, Public Library of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County.

5. Charlotte City Clerk, Minutes of the City Council (Special Meeting September 3, 1935).

6. Charlotte City Clerk, Minutes of the City Council (Nov. 13 1935).

7. Douglas, Ben E., “Ledbetter, L. L., City Treasurer to Ben E. Douglas,” (March 11, 1960), Ben E. Douglas Papers /Manuscript 109 , University of North Carolina, J. Murray Atkins Library Special Collections.

8. United States and Works Progress Administration North Carolina, North Carolina W.P.A.: Its Story (Information Service: 1940) .p1

9. Douglas Ben E., History of the Airport Scrapbooks, storage in the Robinson-SpanglerCarolina Room, Public Library of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County (labeled photographs)

10. Douglas, Ben E., History of the Airport Scrapbooks, storage in the Robinson-Spangler Carolina Room, Public Library of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County (undated unnamed newspaper clipping, circa Dec 1935)

11. Charlotte Observer (April 25, 1982)

12. Charlotte Observer (February 28, 1950)

13. Douglas Ben E., History of the Airport Scrapbooks, storage in the Robinson-Spangler Carolina Room, Public Library of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County.

14. Charlotte News (April 19, 1941).

15. Charlotte News (April 19, 1941); Charlotte Observer (February 28, 1950)

16. Charlotte City Directory (1941, 1942, 1943, 1944, 1945, 1946); Interview with Fred Wilson, President Carolinas Historic Aviation Museum (April 1, 2002)

17. Dedication Program (July 10, 1954), Douglas Airport, Clippings Folder, Robinson-Spangler Carolina Room, Public Library of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County.

18. Kratt, Mary and Mary Boyer, Remembering Charlotte: Postcards from a New South City, 1905—1950, (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2000) p128

19. Interview with Fred Wilson, President Carolinas Historic Aviation Museum (April 1, 2002)

20. Charlotte Observer (October 21, 1992)

21. Charlotte Observer (October 21, 1992)

22. Charlotte/Douglas International Airport, Official Website. Available at: http://www.charlotteairport.com/economic.htm

23. Douglas, Ben E., “Douglas Presents History to Library,” Clippings Folder, Ben E. Douglas Papers /Manuscript 109 , University of North Carolina Charlotte, J. Murray Atkins Library Special Collections.

24. Douglas, Ben E. “‘Dad’ Douglas is on Cloud 9,” Clippings Folder, Ben E. Douglas Papers /Manuscript 109 , University of North Carolina Charlotte, J. Murray Atkins Library Special Collections.

25. Morrill, Dan L., “A Brief History of Streetcars in Charlotte,” Charlotte Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission Website, available at: www.cmhpf.org/essays/streetcars.html

26. United States and Works Progress Administration North Carolina, North Carolina W.P.A.: Its Story (Information Service: 1940) p46.

1. Name and location of the property: The property known as the W.P.A. / Douglas Airport Hangar is located at 4108 Airport Drive in Charlotte, N.C.

1. Name and location of the property: The property known as the W.P.A. / Douglas Airport Hangar is located at 4108 Airport Drive in Charlotte, N.C.