This report was written on November 5, 1986

1. Name and location of the property: The property known as the Jennie Alexander Duplex is located at 1801-1803 East Eighth Street, Charlotte, North Carolina.

2. Name, address and telephone number of the present owner of the property: The owner of the property is:

Mr. Lyman Welton & Wife, Katherine S. Holliday

1803 E. Eighth St.

Charlotte, N.C., 28204

Telephone: 704/374-0294

3. Representative photographs of the property: This report contains representative photographs of the property.

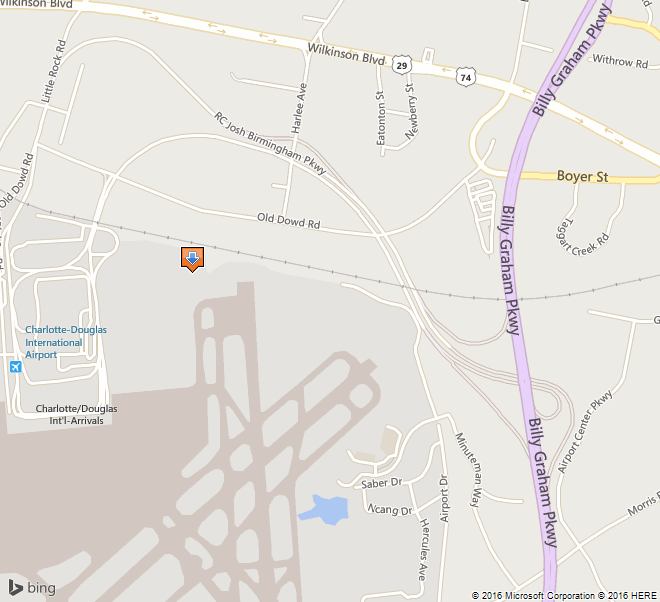

4. A map depicting the location of the property: This report contains a map which depicts the location of the property.

5. Current Deed Book Reference to the property: The most recent deed to this property is recorded in Mecklenburg County Deed Book 4307, Page 755. The Tax Parcel Number of the property is: 127-013-01.

6. A brief historical sketch of the property: This report contains a brief historical sketch of the property prepared by Dr. William H. Huffman.

7. A brief architectural description of the property: This report contains a brief architectural description of the property prepared by Thomas W. Hanchett.

8. Documentation of why and in what ways the property meets the criteria for designation set forth in N.C.G.S. 160A-399.4:

a. Special significance in terms of its history, architecture, and/or cultural importance: The Commission judges that the property known as the Jennie Alexander Duplex does possess special significance in terms of Charlotte-Mecklenburg. The Commission bases its judgment on the following considerations: 1) the Jennie Alexander Duplex, erected in 1922, might be the oldest suburban residence in Charlotte which was initially designed as a duplex; 2) the Jennie Alexander Duplex was designed by James Mackson McMichael, an architect of local and regional importance; 3) the Jennie Alexander Duplex is the only known example of McMichael’s residential architecture which survives in Charlotte and is most probably the only example of a McMichael-designed duplex extant in Charlotte; and 4) the Jennie Alexander Duplex is part of a cluster of homes (it, the John Baxter Alexander House, and the Walter L. Alexander House) which once formed a unique family complex in the Elizabeth neighborhood.

b. Integrity of design, setting, workmanship, materials, feeling, and/or association: The Commission contends that the architectural description included in this report demonstrates that the property known as the Jennie Alexander Duplex meets this criterion.

9. Ad Valorem Tax Appraisal: The Commission is aware that designation would allow the owner to apply for an automatic deferral of 50% of the Ad Valorem taxes on all or any portion of the property which becomes “historic property.” The current appraised value of the improvement is $83,800. The current appraised value of the .459 acres of land is $14,000. The total appraised value of the property is $97,800. The property is zoned R6MF.

Date of Preparation of this Report: November 5, 1986.

Prepared by:

Dr. Dan L. Morrill

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Properties Commission

1225 S. Caldwell St. Box D

Charlotte, N.C., 28203

Telephone: 704/376-9115

by

Dr. William H. Huffman

September, 1986

Walking or riding along East Eighth Street on the part that passes through the tree-shaded Elizabeth neighborhood, one encounters a house on the corner of Lamar Avenue that is rather different most of its neighbors. The duplex at 1803 East Eighth is the former residence of Jane J. (Jennie) Alexander (1861-1932), who had the house built in 1922.

Jennie Alexander was born in Monroe, N.C. at the beginning of the Civil War in 1861. She was the daughter of Dr. Cook Alexander (d. 1882) and Sarah Coburn Stewart Alexander (d. 1902), who had moved to Charlotte from Union County prior to the hostilities, but removed to Monroe for the duration. After the war, the Alexanders returned to Charlotte, where they eventually established themselves as one of the wealthiest and most prominent families of the city. Jennie Alexander, her three brothers (Walter Stewart, William Coburn, and John Baider), and two sisters (Lucy and Mary) all bought and sold real estate in the city, but brothers W. S. and J. B. became two of the most important real estate developers in turn-of -the-century Charlotte.1 It is said that W. S. Alexander (1858-1924) was the first in the city to make the real estate business a profession. In 1899, with Peter Marshall Brown (1859-1913), he organized the Southern Real Estate, Loan and Trust Company, and served as its president from 1908 until his death in 1924, when his brother J. B. Alexander took over the top post. Through his control of the Highland Park Company, W. S. Alexander began the development of the first part of the Elizabeth neighborhood in the late 1890s, in the area on each side of Elizabeth Avenue. By the time the electric trolley line was extended from the Square to Elizabeth College at the top of the hill a mile south of the city in 1903, development of the suburban area began to move at a faster pace.

Two areas just to the north of Elizabeth Avenue began development in 1900, Piedmont Park and Oakhurst, and in 1904, through the Highland Park Co., John B. Alexander and his nephew, W. L. Alexander (Walter’s son) opened up an extension of the original Elizabeth Avenue development to the southeast, which they called Elizabeth Heights. In the Teens and Twenties, many of the city’s prominent citizens as well as outer middle class families built houses in the Elizabeth neighborhood. 3

In 1906, John D. Alexander bought a whole block of land in the Elizabeth Heights section from the Highland Park Company for $3,600.00, which was bounded by Clement, 8th and Lamar on three sides, and the Oakhurst development on the fourth (roughly where Ninth Street would be if it went through). He intended this block to be where he and his family would build their homes, and in 1913 he built a spacious one for himself on the corner of Clement and 8th Avenues.5 Two years later, nephew W. L. Alexander built his own on Clement just up from Eighth Street6 and in 1921, Jennie Alexander bought a 100 x 200 foot on the comer of Lamar and Eighth from J. B. for her new house.7

To design the new residence, Jennie Alexander hired J. M. McMichael, one of the city’s leading architects James Mackson McMichael (1870-1944) was a Pennsylvania native who came to Charlotte in 1901. He was best known for many of the fine churches he designed in his career, many for black congregations. In Charlotte, some of his most important commissions include the old Charlotte Public Library (now demolished), and its companion building on North Tryon Street, the former First Baptist Church, now Spirit Square, the Little Rock A.M.E. Zion Church, now the Afro-American Cultural Center; the Tabernacle A.R.P. Church on Trade Street, the Myers Park Presbyterian Church, St. John’s Baptist Church on Hawthorne Lane; and the North Carolina Medical College building at Poplar and Sixth Streets. In all, McMichael designed twenty-two churches and some one hundred eighty-seven buildings in the Charlotte area, and hundreds more throughout the country. 9 For her residence, Jennie Alexander had McMichael design a duplex, which is believed to be the first one in the city.10 After its completion in 1922, W. S. Alexander’s unmarried daughter, Minnie, moved in with her Aunt Jennie in what they named The Pines.11 The other part of the house was rented to various tenants. For ten years Jennie Alexander enjoyed the peaceful living in that serene part of Elizabeth.

At her death in 1932, Jennie Alexander, who was an active in the Presbyterian Church through her membership in First Presbyterian, as were the other members of her family, willed money to a number of Presbyterian missions and institutions, but her real estate was divided between her brother, J. D, and her nephew.12 For the next twenty years, the house remained in the ownership of her heirs, who in 1952 sold it to Thomas and Comelia Haughton. The present owners bought the property from Mrs. Haughton, then a widow. in 1980. 13 The Jennie Alexander House, through its association with the Alexander family, its place in Elizabeth, and designed by J. M. McMichael is an important thread in the fabric of the city’s history.

Notes

1 Charlotte Observer, Apr. 18, 1932, p. 4; May 30, 1924, p. 1.

2 Ibid; Charlotte Observer, July 28, 1943, p. 12.

3 Thomas Hanchett, “Charlotte Neighborhood Survey”, Charlotte Mecklenburg Historic Properties Commission, 1984.

4 Deed Book 216, p. 16, 4 Sept. 1906.

5 Brochure, “A Tour of Historic Elizabeth”, Charlotte Mecklenburg Historic Properties Commission, 1984.

6 Ibid.

7 Deed Book 454, p. 158, 18 Nov. 1921.

8 City of Charlotte building permit 3505, 22 Dec. 1921.

9 Information on file at Charlotte Mecklenburg Historic Properties Commission; brochure, Historic Architecture Foundation,Washington, D. C, 1984.

10 Ibid.

11 Charlotte Observer, May 30, 1924, p. 1.

12 Will Book W, probated, 22 Apr. 1932.

13 Deed Book 1559, P. 123, 29 May 1952; Deed Book 4307, p. 755, 30 May 1980.

By Thomas W. Hanchett

The Jennie Alexander Duplex is one of three large dwellings built in this block during the 1910s- 1920s for members of the Alexander family, the family who guided the development of the surrounding “streetcar suburb” of Elizabeth. Like the J. B. Alexander House and the W. L. Alexander House around the corner on Clement Avenue, Jennie Alexander’s residence shows influence of the Bungalow architectural style. It is a two-story weatherboarded structure, built as a”side-by-side” duplex,with wide bracketted eaves and chunky brick-columned porches. In both its interior and exterior, the dwelling remains in very good original condition, and the original servants’ quarter (also a duplex) may still be seen behind the house.

The Exterior:

The Elizabeth neighborhood boosted a number of owner-occupied duplexes in the 1920s, particularly on Greenway Avenue, but the Alexander Duplex is by far the largest example of the genre. The duplex sits on a slight rise at the corner of East Eighth Street and Lamar Avenue, with both units fronting on Eighth. The main block of the house consists of a two-story rectangle with a two-story wing set back at each side. A pair of large one-story front porches nestle in the niches created by the set-backs. The “west unit” of the duplex has a small, gabled, one-story kitchen and porch wing at the rear. The “east unit” has a larger rear kitchen wing, plus a one-story hip-roofed library wing which extends from the east side of the duplex.

The main block of the structure has hip roofs. The unusually wide eaves are supported by paired triangular brackets made of large squared timbers. There are two brick chimneys located between the units: an interior chimney near the center of the front roof, and an exterior chimney at the center of the rear facade. Windows have wide surrounds edged in simple molding. Panel blocks are added below the corners of the surrounds for a decorative effect. The windows themselves are double-hung sash units, and most have six panes in the upper sash with one large pane in the lower. An exception is found in the first-floor front facade, which has a pair of tripartite windows, each made up of a central six-over-one-pane unit flanked by two four-over-one-pane units. By the way, the library wing at the east side of the house has windows and surrounds which match the main structure, which is an indication that the wing may have been part of the original design.

The front porches of the duplex are prominent architectural features. Thick red brick columns with corbelled decoration at the tops support the corners. On each set of columns rests a flat porch roof, supported by both curved and triangular brackets. A simple balustrade with square balusters rings the roof, allowing it to be used as a balcony, and in fact a door opens onto it from the upstairs hall. A similar balustrade protects the main level of the porch. Brick steps lead from each porch down to a concrete sidewalk to the street, and this brick blends into the brick of the structure’s foundation.

The Yard and the Servants’ Quarter:

Before moving inside the main house, we will look briefly at the yard and at the Servants’ quarter. The main house sits back from Eighth Street approximately forty feet, in line with its neighbors, and near the center of its lot. Along Eighth Street and Lamar Avenue there is a low concrete wall approximately a foot high with a curved front face. Such walls were found elsewhere in Charlotte’s desirable early-twentieth century neighborhoods, including Dilworth and Fourth Ward, but rarely survive in good condition today. Behind the house is a new wooden fence shielding a newly landscaped back yard. In the back yard is the original servants’ house, a one-story gabled structure similar in form to mill housing of that day. Simple brackets in the eaves and weatherboarded wall section of the main house. The dwelling was originally a duplex, with two front doors. Today the doors remain, but the interior has been gutted and rebuilt under the design direction of owner Katie Holliday as a “bed and breakfast” unit. This early 1980s remodeling also included complete rebuilding of the quarter’s front porch, extension of its rear garage, and addition of a standing-seam sheet metal roof.

The Interior of the “West Unit”:

Looking first inside the “west unit,” we enter through the front door into a stair hall. It contains its original light fixture, a hanging globe. A handsome stair winds up the outside walls. It has a heavy balustrade and square newel with paneled sides and a bowl-like carved top piece. From the stair hall, doorways open into the living room, the dining room, and the breakfast room, giving the first floor an open feeling which is reinforced by the light spilling in from the many windows.

The living room at the front of the house has a wide molded baseboard and a small molded cornice,motifs which are carried throughout the house. A fireplace with a effirgian mantle of red brick and white wooden molding dominates the east wall. French doors in the opposite wall open onto the front porch. The north wall is actually a large opening to the dining room. The opening is flanked by a pair of large square Bungalow-style columns, and is topped by an oversized frieze and cornice. Moving through this opening, one enters the dining room. It continues the decor of the living room, and retains its original cast-metal hanging light fixture. Next to the dining room is a breakfast room, somewhat larger than the “breakfast nooks” typically found on houses of this vintage. The current owners have a molded chair rail here which blends well with the original trim. Behind the breakfast room is the kitchen, the only major room with no cornice molding. The kitchen sink unit and stove appear to date from the 1940s. One corner of the room was long ago walled off for a toilet. At the back of the kitchen is one door to a small pantry, and another door to the small enclosed rear porch.

Upstairs in the “west unit” is a stair hall containing a closet, a door to the front porch roof, and doors to the bedrooms and bathroom. Doors are four-panel units with two small upper panels above two long lower panels. The front bedroom is the master bedroom. It contains a Doric-columned mantel over a fireplace with a cast iron coal grate. A pair of simple electric sconces next to it were designed to light a dressing table. The room contains one closet. Behind the master bedroom is a similarly-sized second bedroom, also with a closet but without a fireplace. The current owners have cut a new door from this room into the “east unit” of the duplex, allowing passage from one side of the duplex to the other. Across the hall from the back bedroom is a much smaller room that may have originally served as a sewing room or child’s bedroom. At the back of the hall is the well-appointed bathroom. It retains its original tub, toilet, white tiled wainscoting, and built-in medicine cabinet with an unusual mirrored “Dutch door.” The only major change have been new sconces flanking the medicine cabinet, and a new pedestal sink in recent years.

Dissimilarities Between the “East Unit” and the “West Unit”:

According to the current owners, a thick brick wall separates the two sides of the duplex, providing a sound and fire barrier. The “east unit” of the duplex is identical to the “west unit” in its molding and mantles, but slightly different in its floor plan. On the first floor, the dining and living rooms are almost the same, except that they are separated by French doors rather than a columned opening. The current owners have added a molded chair rail in the dining room. The stair hall is similar, but the stairs wind in a different direction. Next to the stair hall is the library, not found in the “west unit,” with its own bathroom (original fixtures and tile –except for a new sink — match those seen elsewhere in the house). Behind the stair hall and next to the library is a breakfast room of quite different layout than in the “west unit.” The breakfast room contains an original built-in china cabinet. Behind the breakfast room is a spacious kitchen, with a new chair rail, and with rear doors that lead to a pantry and to an enclosed rear porch. On the second floor of the “east unit,” the two main bedrooms are similar to those already described. But the bathroom is slightly bigger and there is no “sewing room” opening off the upper stair hall. Instead a small room that may have been a nursery opens off the bathroom.

For more information…

1. Name and location of the property: The property known as the W.P.A. / Douglas Airport Hangar is located at 4108 Airport Drive in Charlotte, N.C.

1. Name and location of the property: The property known as the W.P.A. / Douglas Airport Hangar is located at 4108 Airport Drive in Charlotte, N.C.