This report was written on 25 February 1991

1. Name and location of the property: The property known as the Sloan-Davidson House is located at 314 West Eighth Street, Charlotte, in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina.

2. Name, address and telephone number of the present owner of the property: The owner of the property is:

Diane E. LaPoint

311 West Eighth Street

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

Telephone: (704) 3345255

Tax Parcel Numbers: 078-036-08

3. Representative photographs of the property: This report contains representative photographs of the property.

4. A map depicting the location of the property: This report contains maps which depict the location of the property.

5. Current Deed Book Reference to the property: The most recent deed to Tax Parcel Number 078-036-08 is listed in Mecklenburg County Deed Book 5803 at page 916.

6. A brief historical sketch of the property: This report contains a brief historical sketch of the property prepared by Ms. Paula M. Stathakis.

7. A brief architectural description of the property: This report contains a brief architectural description of the property prepared by Ms. Nora M. Black.

8. Documentation of why and in what ways the property meets criteria for designation set forth In N.C.G.S. 160A 400.5:

a. Special significance in terms of its history, architecture, and /or cultural importance: The Commission judges that the property known as the Sloan-Davidson House does possess special significance in terms of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County. The Commission bases its judgment on the following considerations: 1) the ca. 1820’s original section of the Sloan-Davidson House is one of the earliest dwellings in Fourth Ward; 2) the ca. 1890’s enlargement and renovation of the Sloan-Davidson House made it a prominent house in Fourth Ward; 3) the Sloan-Davidson House is architecturally significant for exemplifying the vernacular interpretation of Folk Victorian housing with Queen Anne detailing; 4) the Sloan-Davidson House is one of the few original houses remaining in Fourth Ward; and 5) the Sloan-Davidson House provides valuable insight to the life of city families in early Charlotte.

b. Integrity of design, setting, workmanship, materials, feeling, and/or association: The Commission contends that the architectural description by Ms. Nora M. Black included in this report demonstrates that the Sloan-Davidson House meets this criterion.

9. Ad Valorem Tax Appraisal: The Commission is aware that designation would allow the owner to apply for an automatic deferral of 50% of the Ad Valorem taxes on all or any portion of the property which becomes a designated “historic landmark”. The current appraised value of the improvements is $42,200. The current appraised value of the .098 acres is $35,220. The total appraised value of the property is $77,420. The property is zoned UR1.

Date of Preparation of this Report: 25 February 1991

Prepared by: Dr. Dan L Morrill in conjunction with Ms. Nora M. Black

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission

1225 South Caldwell Street, Box D

Charlotte, North Carolina 28203

Telephone 704/376-9115

Ms. Paula M. Stathakis

The current owner of the home located at 314 West Eighth Street in Fourth Ward believes that part of the structure was built in 1820. It is possible to trace deeds to the property to 1801, but it is unclear how old the structure is. The house is on the Beer’s Map for the city, 1877. It appears that the house was built in two sections. The oldest section includes what is now the kitchen and the dining room. One neighborhood legend is that this segment of the house was built as a shelter for the construction workers who built the Overcarsh House located at the opposite end of the block. 1 If this is the case, this eliminates the possibility that the structure at 314 West Eight Street is the oldest home in Fourth Ward (as has been suggested).

The owner believes that the rest of the house was built in 1890, because during recent renovations, an 1880 nickel was found in a wall as well as a newspaper obituary for Jefferson Davis (d. December 6, 1889). Two shoes were also found in this same wall; one lady’s high top boot and a smaller girl’s canvas slipper. The owner believes that these were deliberately placed with the wall during construction for good luck. The grounds of the property regularly produce antique curiosities, such as small glass bottles, old coins, and nails.

During this same renovation, Roman numerals were found stamped on wall timbers that suggested to the renovation contractor that the walls were prefabricated and put together according to a standard plan. The owner was told that these walls had Sears stamped on them as well and the oldest part of the house was probably an early Sears prefabricated structure. Subsequent inspection of the structure has shown that the house was not a Sears house, and the Roman numerals may simply show the plan of the house as it was designed on the site.

The earliest deed to the property is dated February 18, 1801. John Sloan purchased the 48 acre property from Robert Sloan. 2 Twenty acres of this property were purchased by E. D. B. Sloan in 1836, for $260.20. 3 By the time of the next sale, between E. D. B. Sloan and R. F. Davidson, the property was broken into squares and lots, indicating that the Fourth Ward neighborhood was already blocked out. 4 Among the squares bought by Davidson was number 66, the block in which this property is found. Davidson’s purchase of 21.5 acres cost $300.

Davidson sold the property in 1854 to Daniel H. Byerly for $200. 5 The property remained in the Byerly family until the end of the nineteenth century. After this time, it was purchased by several other people, 6 and remained with the heirs of T. R. Magill until 1963. After this time, the property suffered along with the general decline of the Fourth Wand neighborhood. It was sold in 1976 to Berryhill Preservation, Inc. Berryhill Preservation, Inc., was organized to salvage and restore the Fourth Ward area during a period of flight to Charlotte suburbia.

The neglected house was purchased by Christopher and Pam Geiger in 1977 for $13,000. They learned about the property because it was featured in a story about Fourth Ward renovation in The Charlotte Observer. 7 The house has been extensively renovated since 1976 and stands renewed as does the rest of the Fourth Ward.

Notes

1 Information was gathered from an interview with Ms. Diane LaPoint, current owner of the property, 16 October 1990.

2 Deed Record Book 17-690, 18 February 1801. Register of Deeds, Mecklenburg County Courthouse.

3 Deed Book 4-486,30 December 1836. Register of Deeds, Mecklenburg County Courthouse.

4 Deed Book 2-222, 10 March 1847. Register of Deeds, Mecklenburg County Courthouse.

5 Deed Book 3~501, 21 August 1854. Register of Deeds, Mecklenburg County Courthouse.

6 Chain of Title between 1892 and 1976:

T. M. Shelton, Deed Book 84-498, 19 Dec 1892;

Kate Russell, Deed Book 116-118, 11 January 1895;

T. R. Magill, Deed Book 123-630,8 March 1898;

after Magill’s death the property was conveyed to his heirs and descendants as follows: Mary M. Horton, Bess H. Edwards, and M. E. Gano who sold the property to M. S. Alverson, Jr., and his wife, Deed Book 3888-389,18 October 1976;

they sold to M. S. Alverson, Deed Book 3888-395,17 October 1976;

Alverson sold to Berryhill Preservation, Inc.

7 “For Sale: A Bit of Bygone Days,. The Charlotte Observer: 10 November 1976 (n.p.; article lent by Ms. Diane LaPoint).

Ms. Nora M. Black

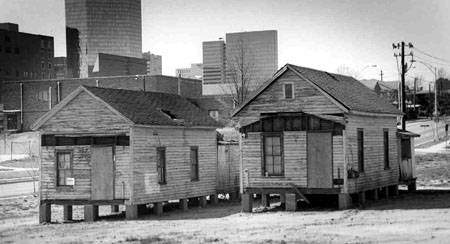

The Sloan-Davidson House is located on the north side of West Eighth Street The house is within Fourth Ward between North Pine Street and North Poplar Street. It is one of the few houses in Fourth Ward that is original to its site; additionally, it has not been reoriented an its site. The front or south facade of the house faces West Eighth Street; the rear or north facade overlooks a small yard with a gazebo. The Sloan-Davidson House shares the West Eighth Street streetscape with the Overcarsh House (326 West Eighth Street), a Queen Anne style house.

The Sloan-Davidson House is believed to be an enlargement of a two room building or cottage that originally stood on the site. An investigation of the attic revealed a portion of a smaller roof with wood shakes encapsulated by the larger roof. The wood shake roof portion is located beside the chimney which separates the living room and the dining room. Furthermore, a portion of an old sill is visible near the same chimney in the crawl space. 1

Exterior

As mentioned in the Historical Sketch, it is believed that the two room cottage grew into a Folk Victorian House 2 in approximately 1890. A photograph from “An Inventory of Older Buildings in Mecklenburg County and Charlotte for the Historic Properties Commission” conducted in the summer of 1975 shows a house exterior much like the present one with three notable exceptions. The 1975 photograph shows flat, jigsaw-cut trim at the top of the porch supports; a simple repeating cross-in-square pattern forms the balustrade. The two front gable ornaments had decorative detailing that appears to consist of flat boards parallel to the ground connecting the spindlework. Renovations in the late 1970’s have replaced these three Folk Victorian details with the Queen Anne style of decorative detailing.

The siding is painted lapped horizontal boards; much of it is original. The current owner has replaced some rotten boards with weatherboarding of equal width. All siding is painted dark blue; the trim is painted white. The spindlework is painted white with mauve accents. The wooden porch floor is painted gray. The underpinning of the house consists variously of red brick and of stuccoed concrete blocks.

The black composition shingle roof has a moderate pitch. Due to the complexity of the roof, the roof pitch and the black shingles, there is a great deal of contrast between the roof planes and the blue wall surfaces. The black roof gives the house a heavy, weighted appearance. The boxed eaves have a moderate overhang with bed moldings. There is a moderate overhang on the gable ends with wide shingle moldings. The simple window surrounds consist of painted white boards. Many windows in the house have leaded glass and appear to be original. The current owner has installed interior storm windows that are not visible from the exterior

At a quick glance, it would seem that the Sloan-Davidson House has a compound, gable-front-and-wing shape; the ground plan of the house would appear to be that of a side-facing T with a hip-roofed porch. Upon investigation, it become obvious that the builders were not content to stop with a simple Folk Victorian shape for this small one-story house. Influenced by the Queen Anne style that was popular in Fourth Ward, the builders have constructed a complex tripped roof with cross gables. Yet even the tripped roof is an illusion, for the top of the hip is actually flat and contains a skylight over the center passage. Unlike the Queen Anne style houses, the gables are not secondary to the fake tripped roof but are of equal height. The gable pitch varies around the house facades. Furthermore, them is an irregularity in the ground plan to avoid a flat front wall surface; the front porch wraps around a small foyer that precedes the center passage.

The very complex roof divides the house and speaks of additions and renovations over the many years of life of the Sloan-Davidson House. The south (West Eighth Street) facade is three units wide. The west unit is gablefront with one centered 2/2 double-hung sash; it has an interior masonry chimney exiting at the ridge. There is a wooden, louvered vent in the gable as well as a Queen Anne style gable ornament of spindlework with beads. The center unit houses the entry with its glass and wood-paneled door; this unit gives the illusion of being tripped roofed The east unit has one 2/2 double-hung sash; it has a narrow, steep gable framed into a cross-gabled roof. The east unit gable ornament is spindlework with beads.

The porch fronts both the center unit and the east unit of the house. The hip-roofed porch wraps around the foyer of the house. The ceiling is board with the complex framing visible. The wooden porch supports are turned spindles connected with lace-like brackets and friezes.

The east facade of the house consists of four units. The east-most wing is one unit deep; it has a single double-hung 2/2 sash centered under the gable. The window-less second unit formed by a north-facing cross gable holds the electrical service panel. The window-less third unit is formed by a cross gable contained within the larger cross gable of the second unit. The fourth window-less unit is a small shed roofed addition.

The north (rear) facade of the house consists of three gables with a shed roofed porch. The east gable of the north facade has a single fixed pane of glass within a Gothic arch. That same cast gable also has a smaller, lower gable extruded from it The smaller gable has a high octagonal window. The third gable, having legs of unequal length, covers the kitchen area. The shed roofed porch does not extend the full width of the north facade; however, the east end of the porch has been enclosed to form a laundry/storage area. The remainder of the porch shelters two windows on either side of a double door that enters directly into the kitchen. The two ten light doors were added to the house during the 1970’s renovations. The east window is a 6/9 double hung sash; the west window is a 6/6 double hung sash. The eave of the porch roof is trimmed with flat, jigsaw cut trim. The square porch supports are trimmed with Queen Anne spindlework matching that of the front porch.

The west facade is the least complex of the Sloan-Davidson house. It is three units wide. A centered gable has a wooden louver for attic ventilation but no gable ornament. Each unit has one centered 6/9 double hung sash.

Interior

The plan of the house is also complicated by old additions and 1970’s renovations. It must be remembered that during the late 1970’s, the house was near collapse. It had to be renovated and repaired to bring it to a livable state. Some detailing was broken beyond repair, rotten, or simply missing. The damaged plaster had to be replaced with gypsum wallboard. Had these renovations not occurred, it would have been torn down. Then the lot might have been used as the site for a modern house similar to those constructed on either side of the Sloan-Davidson House.

The west section of the house consists of a living room, dining room, and kitchen; they are in line from front to back of the house. The wall between the living room and dining room has been removed. The two rooms are divided by a fireplace with open front and back; spindlework hanging from the ceiling serves as a further room divider. The living room is approximately fourteen feet square with hardwood floors of random width. The gray walls (at some places plaster and other places gypsum board) have a white chair rail and crown moldings. Half-corner posts beside the archway to the foyer are carved and dimpled. The chair rail and the crown molding continue throughout the dining room. Window surrounds with carved corner blocks in both rooms are painted white.

The dining room and the kitchen are believed to be the 1820’s two room building that was first constructed on the site. The dining room is approximately fourteen feet square with hardwood flooring. The original front door of the Sloan-Davidson House has been installed between the dining room and the kitchen. it is an elaborately carved door with a large pane of glass bounded by smaller panes over two carved wooden panels.

The kitchen has undergone much renovation due to the collapse of the ceiling during the 1970’s. The brick floor was installed in 1974; the previous wooden floor had rotted. The wainscot is stained a dark brown as are the door and window surrounds. Wood beams have been added to the ceiling.

The center section of the house is devoted to a small foyer and a center passage which the present owner uses as a parlor. There is a bedroom at the north end of the center passage (back of the house). A small bathroom opens off the north bedroom. The foyer entrance has a carved door surround with corner blocks. The door is also carved and consists of two small square panels over a single large glass panel over two rectangular vertical panels.

A fixed sash on the east side of the foyer has a square, clear pane of glass surrounded by smaller square panes of stained glass The foyer is divided from the parlor by beaded spindlework within the framework of the door surround. The parlor (center passage) has a dark wainscot and door surrounds. The ceiling of the parlor is taken up by a stained glass window; the current window replaces one destroyed by Hurricane Hugo in 1989.

The east section of the house consists simply of a rectangular bedroom with a bathroom on the north side. According to the current owner, both bathrooms were added in 1974. The house has been updated to include air conditioning and a gas furnace. Interior storm windows were added for energy conservation. A wood stove insert was added to the parlor fireplace.

The parlor fireplace is part of an interior chimney system that serves three rooms. Corner fireplaces have a long history in North Carolina having been introduced by German immigrants as early as the 1770’s in their Continental plan house. 3 The parlor fireplace has a mantle of dark stained wood surrounding a mirror. The actual parlor fireplace is of normal size; however, the overall impression created by the massive, extended mantelpiece is that of a much larger fireplace. The east bedroom has a carved fire surround painted white around tiles with a delicate floral pattern. The north bedroom also has a painted, carved fire surround.

Door and window surrounds in the two bedrooms have elegantly carved corner blocks; the elaborate surrounds are painted white. Chair rails have been installed in both bedrooms. Many of the interior doors are two panel wooden doors with early hardware. A two panel wooden door, possibly removed from an interior opening, has been installed in the laundry/storage area on the back porch.

The Sloan-Davidson House has survived the ups and downs of the area of Charlotte known as Fourth Ward. Throughout its life, it has changed from a two room cottage to a Folk Victorian dwelling with Queen Anne details. The current owner, who was raised nearby on Seventh Street, said that her grandmother attended church circle meetings in the Sloan-Davidson House. For the owner, the house has been an opportunity to return to the warmth of home in the center of Charlotte.

Notes

1 Interview with Milton Grenfell . Mr. Grenfell visited the Sloan-Davidson House and inspected the attic and crawl space in May, 1990.

2 Virginia & Lee McAlester, A Field Guide to American Houses (New York, 1986),309-317.

3 Doug Swaim, “North Carolina Folk Housing,” in Carolina Dwelling, ed. Doug Swaim, (Raleigh, N.C., 1978), p.35.