CHARLOTTE SUPPLY COMPANY BUILDING

Click here to view photo gallery of the Charlotte Supply Company Building.

1. Name and location of the property: The property known as the Old Charlotte Supply Company Building is located at 500 South Mint Street, in Charlotte, North Carolina.

2. Name, address, and telephone number of the present owner and occupant of the property: The present owners of the property are:

Charlotte Supply Partners

P.O. Box 35566

Charlotte, NC 28235

Telephone: Not Listed

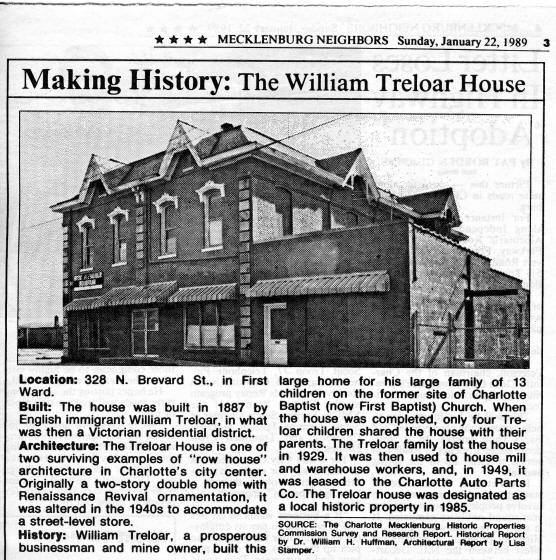

3. Representative photograph of the property: This report contains a representative photograph of the property.

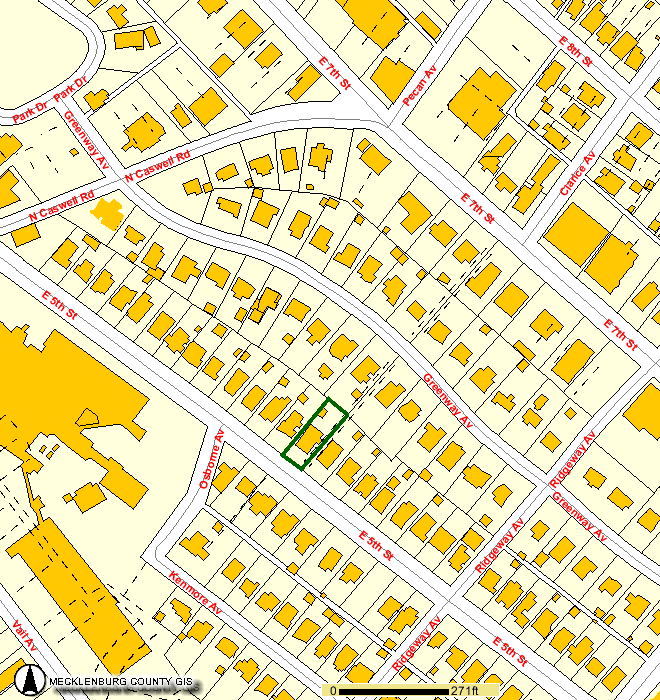

4. A map depicting the location of the property: This report contains a map which depicts the location of the property.

6. A brief historical sketch of the property: This report contains a brief historical sketch of the property prepared by Dr. William H. Huffman.

7. A brief architectural description of the property: This report contains an architectural description of the property prepared by Odell Associates, Inc.

8. Documentation of why and in what ways the property meets the criteria set forth in N.C.G.S. 160A-399.4:

a. Special significance in terms of its history, architecture, and/or cultural importance: The Commission judges that the property known as the Old Charlotte Supply Company Building does possess special significance in terms of Charlotte-Mecklenburg. The Commission bases its judgment on the following considerations: 1) D. A. Tompkins, famous New South prophet, founder of the Charlotte Observer, and leading industrialist, was one of the founders of the Charlotte Supply Company 2) the Charlotte Supply Company, founded in November, 1889, was a manifestation for over seventy years of the importance of the textile industry in Charlotte-Mecklenburg; 3) the current building, designed by Lockwood, Greene and Company and completed in November, 1923, is an especially fine example of industrial and warehouse construction in the 1920s; and 4) the recent conversion of the Charlotte Supply Company building into offices has adhered to the highest standards of sensitive preservation and adaptive reuse.

b. Integrity of design, setting, workmanship, materials, feeling and/or association: The Commission contends that the attached architectural description by Odell Associates, Inc. demonstrates that the Old Charlotte Supply Company Building meets this criterion.

9. Ad Valorem Tax Appraisal: The Commission is aware that designation would allow the owner to apply for an automatic deferral of 50% of the Ad Valorem taxes on all or any portion of the property which becomes “historic property.” The current appraised value of the one acre of land is $60,980. The current appraised value of the building is $95,200. The total current appraised value is $156,180. The property is zoned I3.

Date of Preparation of this report: September 6, 1983

Prepared by: Dr. Dan L. Morrill, Director

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Properties Commission

218 North Tryon Street

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

Telephone: (704) 376-9115

The growth of Charlotte from a rural village in 1850 to a thriving center of the Southern textile industry by the end of the century was the result of several factors: its locale in the cotton-producing region, the development of rail transportation, the availability of power, low taxation and cheap labor. Starting in 1852, when Charlotte was linked by rail with Columbia, SC, giving it easy access to the sea for the first time, and followed in 1855 by completion of a line to Norfolk, the city became a cotton trading center. By 1875, when Charlotte was connected to many of the surrounding cotton-producing counties by rail as well as being located on the line stretching from New York to New Orleans, cotton trading had increased from less than three thousand bales annually twenty years before, to 40,000 bales that year. It was not too long afterwards that a quickening interest in the industrial potential of the New South gathered momentum, and by 1880 a number of textile mills built in the Piedmont crescent from Virginia to Alabama, with Charlotte in the center, were already operating. In 1880, the South had just over a half million spindles operating, but by 1900, this number had jumped to four and a half million, and ten years later it was 11.2 million. Although the battle cry was to move the cotton mills from New England closer to the source of supply, the fact is that the Southern mills were, even in 1922, eighty-four percent owned by Southern capital, and it was-only after that time when large amounts of northern capital moved into the region and the New England mills suffered great decline. Many individuals, however, who were trained in textile manufacturing in the north, came south during this period to take advantage of the tremendous growth of the industry here. Such was the case of those who founded and built up the Charlotte Supply Company.

Charlotte’s first cotton mill, and the only one in Mecklenburg County at the time, was built in 1880. Originally operating 6240 spindles which was eventually increased to 9000 in the one-story building, the Charlotte Cotton Mills was founded by J. M. Dates (1829-1897) and his three nephews, all of whom were cotton traders in the city.5 In 1882, a thirty-year-old native of South Carolina who had been educated and trained in manufacturing in the North, Daniel Augustus Tompkins (1852-1914), came to Charlotte as a representative of the Westinghouse Company to sell textile machinery. Recognizing the great potential for textile development in the region, in 1884 he started the D. A. Tompkins Company, a machine shop, contracting and consulting engineering firm, which was greatly responsible for the growth of textile manufacturing and related businesses in the Piedmont Carolinas. In his thirty-two year career in Charlotte, Tompkins, a tireless advocate of Southern industrialization, constructed over one hundred cotton mills, various fertilizer works, electric light plants and ginneries. He transformed the cotton oil of the region from a waste product to a major industry by building about two hundred processing plants and helping to organize the Southern Cotton Oil Company.6

Tompkins, who was instrumental in establishing textile schools at North Carolina State University, South Carolina and Mississippi, was interested in every phase of the textile business. Thus in 1889, when the D. A. Tompkins Company completed Charlotte’s second, third and fourth cotton mills (the Alpha, Ada and Victor), he was also involved in establishing the Charlotte Supply Company.7 On November 7, 1889, the Charlotte Supply Company was incorporated by E. A. Smith, D. A. Tompkins and R. M. Miller, Jr., who were the sole subscribers of the 250 shares of stock with par value of one hundred dollars.8 The D. A. Tompkins Company interest in the new “mill furnishers” corporation is clear, since R. M. Miller, Jr. (1856-1925) was also the secretary-treasurer of Tompkins’ firm. (Tompkins also built and headed Charlotte’s sixth mill, the Atherton, in 1893, and Miller was president of the city’s tenth, the Elizabeth Cotton Mill, in 1901).

The president of the new mill supply company, Edward Arthur Smith (1862-1933), was a native of Baltimore, Maryland, who came to Charlotte as a young man to be the traveling representative for Thomas K. Carey and Son, an industrial supply firm of Baltimore. Located at 20-22 East Fourth Street in Charlotte, the company advertised itself as “general cotton mill furnishers, manufacturers of leather belting, dealers in machinery, machinist’s tools, etc.” Indeed, for most of its years of operation, it was the intention of the company to be able to supply a textile mill with every piece of equipment, machinery, tools, belts and replacement parts, large or small, which would be necessary for its operation. Since the textile machines of the time were belt-driven, manufacturing leather belts also provided a steady source of sales.

By 1900, mill growth in the several-county area around Charlotte had progressed rapidly to provide customers for the supply company. In North Carolina, Gaston County had 32 mills; Alamance County, 23; Guilford, 10; and Mecklenburg, 19 (the city of Charlotte held eight of these); but even greater growth was yet to come.12 In that year, Smith, Tompkins and Miller sold the supply company to three natives of Warren, RI, and Smith subsequently built the Chadwick Mill in Charlotte (1901), another in Rhodhiss, NC in 1910, and the Phoenix Mill in Kings Mountain, NC five years later. The new president and principal stockholder was now Henry C. Clark (1850-1917), the vice-president Jerimiah Goff (1858-1931) and the secretary-treasurer was Henry Walter Eddy (1857-1932). As a youth of nineteen, Clark began his textile career in the card room of the Warren Manufacturing Company, where he eventually advanced to superintendent of the 100,000-spindle mill. In the early 1890s, he took a position with Brown Brothers of Providence, RI, for which firm he traveled extensively in the South for several years. A few years later, he was one of the organizers of the Standard Mill Supply in Providence, and in 1899 was elected mayor of Warren. The following year he sold his business interests and resigned the office of mayor to move to Charlotte, where he ran the Charlotte Supply Company for seventeen years.

In 1914, the Certificate of Incorporation was amended to reflect some changes in the structure of the company. The length of existence of the business was changed from thirty to sixty years, and the amount of authorized capital stock was raised from 250 to 1250, which remained at the same par value. The outstanding shares were distributed as follows: H. C. Clark, 143 shares; E. B. Graham, Sr., the new vice-president, 60 shares; and H. W. Eddy, 47 shares.16 The greatly increased stock authorization was designed to raise money for an expanding business to meet the needs of the ever-growing textile plants in the Piedmont. Before the expansion plans could be fully carried out, however, H. C. Clark died in 1917, and was succeeded as president by his son, Albert Barton Clark (1892-1945), who had moved to Charlotte with his parents in 1900, and attended Alabama Presbyterian College.17

Just two and one-half years after taking over the leadership of the firm, A. B. Clark started to move ahead with plans for expansion. On January 10, 1920, the company purchased a corner parcel of land in Charlotte’s Third Ward which had 150 feet frontage on Mint Street and went back 350 feet on West First Street to the Southern Railway tracks.18 The large engineering firm of Lockwood, Greene and Company (which also had offices in Atlanta, Chicago, New York, Detroit, Cleveland, Montreal and Paris) was engaged to design a new five-story building for the mill supply company, and the plans and specifications for it were completed in November, 1923.19

The following February, 1924, the contract for construction was let to the Charlotte firm of Blythe and Isenhour (John F. Blythe and William L. Isenhour, Sr.) for a concrete and brick building with 21-inch thick walls of five stories and measuring 40 by 150 feet at the base. It was estimated to cost $65,000.00. Construction of the new place of business took a year, and was completed in March, 1925. The formal opening of the new building, where leather belts were manufactured on the fourth floor, parts and machinery were warehoused on the other floors, and offices were located in front of the first floor, was modestly announced in a newspaper advertisement offering its services to the public. Undoubtedly it had long been announced to its mill customers in person. From the time of its original construction and continuing to the present, the Charlotte Supply Company building has dominated the Third Ward landscape of Charlotte in its immediate four-block square area, which is still the case today.

The decision to build a new building was a sound one at the time, given the state of the industry in the region. A boost to the building of new mills came in the 1880s with the use of steam boilers to run the machinery instead of relying purely on water power, and with the introduction of electric motors in the 1890s. In 1905, James B. Duke, the tobacco magnate, and an engineer, William S. Lee, organized the Southern Power Company (later Duke Power Co.), and by 1925, this dynamic power source had ten hydroelectric stations along the Catawba-Wateree River system which supplied electricity for three hundred cotton mills as well as many cities and towns of the Piedmont Carolinas. The result of similar developments elsewhere and new inventions in the industry caused the number of spindles in the South to jump from 4.4 to 17.3 million, an increase of 293 percent, from 1900 to 1925.23 As can be seen from figure 1, in 1925 Charlotte was in the center of a dense concentration of the Southern textile industry, and therefore the Charlotte Supply Company was in an advantageous geographical position with good rail transportation.

By the time the Charlotte Supply Building was built in 1925, the days of rapid expansion in the textile industry were over, but the Southern mills fared much better than those in the North because of the advantage in the cost of labor. Between 1923 and 1933, New England lost forty percent of its mills and over half of its laborers, while in the South textile employment rose seventeen percent.24 Thus through the leveling off period in the Twenties and the Great Depression of the Thirties, the Southern mills continued to operate for the most part, if sometimes at a lower level. World War II and the postwar boom brought a tremendous demand for textile goods which lasted until relatively recent times when the industry was faced with increasing foreign competition.25

Although no sales figures are available, one can assume that the fortunes of the Charlotte Supply company rose and fell with those of the industry as a whole. When A. B. Clark retired from the presidency of the company in 1942, he was succeeded by Eugene B. Graham, Sr. (1874-1947), who had, as mentioned earlier, joined the company in 1914. When Graham died five years later, he was followed as head of Charlotte Supply by another longtime employee, Palmer G. Black (1882-1976). Without doubt, the long tenure with the company of Graham and Black contributed greatly to its success. Black began his sixty-two-year-long service with Charlotte Supply in 1908 as a “drummer,” or outside salesman of mill supplies. For all of those years until his retirement in 1970 at the age of eighty-seven, he made weekly visits to industrial plants, primarily textile mills, in the Piedmont region of North Carolina. In the early days, he would take the train from Charlotte to such towns as Lincolnton, Newton, Conover, Hickory, Rhodhiss, Granite Falls, Hudson and Lenoir; for the outlying towns it was necessary to hire a wagon and team by the day. Once the automobile became a reliable means of transportation, he mostly counted on Buicks and Packards to take him on his rounds, but the first one was a Dodge purchased in 1918.

Much of Palmer Black’s long-lived success was due to his personality. He was known for his steady, genteel manner which incorporated unfailing common sense and a fine sense of humor. His unusual memory carried the company’s entire inventory, and he carefully cultivated the friendship of the machinists, purchasing agents and top executives of all the plants he visited in the Piedmont. This familiarity and experience with his products and his customers paid off to the extent that there were some years when Palmer Black was responsible for about half of the company’s sales, in addition to earning him and his company great respect throughout the industry in the region.

When Palmer Black became president of the company in 1947, he continued his duties as outside salesman, and four of E. B. Graham, Sr.’s children constituted the remaining operating officers: E. B. Graham, Jr. (1897-1970), vice-president and manager; Thomas P. Graham, vice-president; Robert G. Graham (1912-1982), secretary; William A. Graham, treasurer. The business operated under this structure until 1969 when it was bought out by Arthur Gould Odell, Jr., who heads the Charlotte architectural firm of Odell Associates. Shortly thereafter, Palmer Black and E. B. Graham, Jr. retired from the business, and a new firm was set up under the name of Graham Supply Company under the direction of Robert and William Graham. Under this arrangement, Charlotte Supply continued to own the building and provided the new company with inventory finance service, but in December, 1971, Charlotte Supply was reactivated as a mill supplier and the Graham company liquidated. In June, 1975, all the inventory of Charlotte Supply Company was sold to the Atlas Supply Company, a Winston-Salem firm with a branch office in Charlotte.30 Thereby almost nine decades of a business tradition in the textile industry of the Piedmont Carolinas came to an end. The company itself continued on with auto leasing, downtown parking and printing interests until recently.

In recent months, the Charlotte Supply Company building has been renovated and adapted for office space. The work was carefully done to preserve it in as nearly original condition as possible, the thus a landmark, which at one time was symbolized by the word “Charlotte” painted on its roof so that airplanes flying overhead could identify the city, will be preserved as part of the heritage unique to the region.31

NOTES

1 LeGette Blythe and Charles Brockman, Hornet’s Nest: the Story of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County (Charlotte: McNally of Charlotte, 1961), p. 21.

2 Beasley and Emerson’s Charlotte Directory for 1875-76 (Charlotte: Beasley and Emerson, 1876?), p. 141.

3 Gilbert Merrill and Alfred Macormac, American Cotton Handbook, 2nd ed. (New York: Textile Book Publishers, 1949), p. 23.

4 George B. Tindall, The Emergence of the New South (New Orleans: Louisiana State University Press, 1967), p. 76.

5 Charlotte Observer, Dec. 28, 1897, p. 6.

6 George T. Winston, A Builder of the New South: Being the Story of the Life Work of Daniel Augustus Tompkins (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1920), passim.

7 Dan Morrill, “A Survey of Cotton Mills in Charlotte,” Charlotte Mecklenburg Historic Properties Commission, 1979, p. 2.

8 Mecklenburg County Corporation Book A, p. 146.

9 Morrill, p. 3.

10 Charlotte Observer, May 1, 1933, p. 1.

11 Charlotte City Directory, 1897/98, p. 149.

12 Holland Thompson, From the Cotton Field to the Cotton Mill (Freeport, N.Y.: Books for Libraries Press, 1971), p. 76.

13 See note 10.

14 Charlotte City Directory, 1902, p. 236.

15 Charlotte Observer, June 17, 1917, p. 11.

16 Certificate of Amendment, Secretary of State’s Office, Raleigh, NC.

17 Charlotte News, June 13, 1945, p. 1B. No further information on A. B. Clark has been uncovered.

18 Mecklenburg County Deed Book 419, p. 102.

19 Plans and specifications in possession of Odell Associates, Charlotte, NC.

20 Records of Blythe and Isenhour, Charlotte, NC; City of Charlotte Building Permit No. 5000 dated March 3, 1924.

21 Records of Blythe and Isenhour. Actual cost was $54,576.31.

22 Charlotte Observer, March 15, 1925, p 11D.

23Merrill and Macormac, pp. 26, 28; Tindall, p. 74.

24 Tindall, p. 78.

25 Ibid., p. 78 et passim.

26 Charlotte City Directory, 1934, p. 140; Ibid., 1942, p. 162; Charlotte News, March 8, 1971, p. 1B; Hickory Daily Record, January 23, 1970, p. (?).

27 Interview with David Black, Charlotte, NC, 6 April 1982.

28 Charlotte City Directory, 1948/9, p. 152.

29 Interview with Wayne Beachum, President of Charlotte Supply 1978-80, controller, Odell Associates, 31 March 1982.

30 Ibid.

31 Interview with William A. Graham, Charlotte, NC, 3 April 1982.

The Charlotte Supply Company Building, with its entrance on South Mint Street yet its principal facade facing West First Street, is a four story (plus basement) brick building measuring forty feet on its east front and west rear elevations and 127 feet along its north and south side elevations. While the building was constructed as the offices, manufacturing facility, and warehouse for the Charlotte Supply Company the industrial function of the structure is enlivened with a program of classical ornament and balance symmetrical proportion which provides the building a handsome impressive appearance. The north elevation parallel to West First Street received the principal focus of the designer’s talents and would appear to have been designed to impress both the pedestrian and others traveling along NC 16, West Trade Street–the principal east-west artery out of downtown Charlotte. When erected, the building towered above its neighbors and continues to be a landmark in the near downtown landscape of Charlotte’s Third Ward.

The Charlotte Supply Company Building was designed by Lockwood, Greene, and Company Engineers who for some time maintained an office in Charlotte in the Piedmont Building in addition to offices in Atlanta, Chicago, New York, Detroit, Cleveland, Montreal and Paris. Prints of the original drawings, dated 16 November, 1923 to 16 April 1924 together with construction specifications are in the possession of Odell Associates, Inc., architects for the present owners of the building. These prints consist of Sheets A-201 (Site Plan, Foundation Plan, Basement Floor Plan), A-202 (Plans of First, Second, Third and Fourth Floors), A-203 (Building Sections and Stair Section), A-204 (Elevations and Wall Section), C-201 (Power and Light Wiring Plans) plus numerous multisized and multiscale drawings of details and shop drawing.

The building rests on a full basement covered with concrete having a skim coat finish. The grade of the lot on which the building was erected slopes to such an extent that the first story front east entrance is at street level while the entrance into the basement at the back of the building is also at ground level. There are windows along the north and west sides in the basement wall.

The east front elevation has a symmetrical three bay division with the first story being taller than the three stories above. It can be interpreted as the base in the three part division of the classical column–the base, shaft, and the capital which was often used as the organizing device for the composition of elevations on commercial architectural forms in the late 19th century and to the present. The entrance is set in the center bay below a full transom. The large window openings to either side are slightly taller, however, the projecting vertical elements on the lintel band–representing keystones-above the openings carry at the top of the first story elevation–and along the side elevation-and serves as the base for the shallow three-story brick pilasters which rise to the cornice band at the top of the fourth story defining the three bays. These pilasters have a soldier row at the top whose form is repeated along the top and bottom of the large window openings. At the windows the soldier rows act as a self surround for the openings.

All the window openings have terra cotta sills. The glazing in the openings appears as one window unit but appear to be a pair of units four panes wide and five panes tall. The panes measure twelve inches in width and eighteen inches in height. The bottom two ranks of panes are fixed. The two center panes in the third and fourth rows form an element which pivots for ventilation; a pull chain and spring catch on the interior operates them. The top rank of panes per panel is also fixed.

The definition of the bays on the front elevation and their finish is repeated in the east. Most bays on both side elevations which serve as cantons for the front elevation and in the case of the bay on the north elevation, it is but one of the two framing elements enclosing the broad facade. The entablature continuing across the front elevation, the north side elevation and the east most bay of the south elevation consists of a terra cotta architrave across the top of the pilasters, a brick frieze and a terra cotta cornice. A shallow brick parapet capped by a terra cotta coping carries along the top of the cornice and breaks upward above the entrance on the front elevation. As noted above, the north side elevation is the most elaborate and boasts the name of the company “THE CHARLOTTE SUPPLY COMPANY” in bronze letters in a terra cotta panel–nine bays wide–which is set into the entablature’s brick frieze. The tall vertical panel seen on the first story bays of the east elevation is repeated in the canton-like bay, however, the remaining ten bays of the first story repeat the size and glazing of the front elevations’ other windows being eight panes across and five panes in height. On the shaft of the cantons (the end bays), the second, third and fourth stories have the same size openings and glazing; however, in the nine center bays of each story are long horizontal window strips eight panes wide and but two high. The tops of these openings are level with the tops of the larger openings and in elevation this horizontality is reinforced by the terra cotta panel in the frieze.

The south elevation is largely blind and broken pilaster strips responding to those on the opposite elevation. A flue stack rises above the parapet along the elevation in the back center of the elevation and is flanked on the west by window openings at each level which provide light into the interior stair well. In the eighth bay (from the front of the building) the wall continues above the parapet line to form a clearing for the elevator in the shaft behind this bay. Window openings occur in the third and fourth story level of this bay. There are three (total) additional random openings in the ninth and tenth bays.

The rear (west) elevation maintains the same pilaster spacing from the first floor to the top of the parapet wall of the front (east) elevation, but without the brick and terra cotta ornamentation. Windows in the second, third and fourth floors are identical to those in the front (east) elevation. Windows at the first floor in the middle bay and northernmost bay are identical to those on the north elevation first floor for ten bays from the west end. The southernmost bay of the first floor is solid to cover the concrete vault behind it. The basement level has a window in the center bay and pairs of doors in the northernmost and southernmost bays which served as truck dock service doors.

The interior of perimeter walls are exposed but painted brick. The structure consisting of pipe columns, steel beams and wood mill deck is entirely exposed. Light fixtures are pendant mounted from the wood deck as is the sprinkler system. The finished floor is 1″ wide maple flooring except in the basement where it is concrete. The tenant for the renovated project is requiring carpet floor covering.