- Name and location of the property: The property known as the Massey-Clark House is located at 232 North Trade Street in Matthews, North Carolina.

- Name and address of the present owners of the property:

The Town of Matthews

232 Matthews Station Street

Matthews, North Carolina 28105

(704)-847-4411

- Representative photographs of the property: This report contains representative photographs of the property.

- Map Depicting the location of the property: Below is a map depicting the location of the property. The UTM coordinates are 525412E 3886083N.

- Current deed book reference to the property: The most recent deed book reference to this property is recorded in the Mecklenburg County Deed Book 3988, page 416. The tax parcel number is 21501203.

- A brief historical sketch of the property: This report contains a brief historical sketch of the property.

- A brief architectural description of the property: This report contains a brief architectural description of the property.

- Documentation of why and in what ways the property meets the criteria for designation as set forth in N.C.G.S. 160A-400.5:

Special significance in terms of its history, architecture, and/or cultural importance: The Commission judges that the property known as the Massey-Clark House does possess special historic significance in terms of Charlotte-Mecklenburg. The Commission bases its judgment on the following considerations: 1.) The Massey-Clark House is one of the oldest extant buildings in Matthews. 2.) The Massey-Clark House is an excellent example of hall-and-parlor style architecture. 3.) The Massey-Clark House is an important remnant of a once rural small town community and is, therefore, reminiscent of a way of life that has virtually disappeared in Mecklenburg County.

- Ad Valorem tax appraisal: The Commission is aware that designation would allow the owner to apply for an automatic deferral of 50% of Ad Valorem taxes on all or any portion of the property which becomes designated as a “historic landmark.” The current appraised value of the lot is $83,100. The appraised value of the building is $39,300. The total tax value is $122,400.

This Report was prepared by Hope L. Murphy (May 2006).

Historical Overview:

The Massey-Clark House is one of the oldest extant residences in Matthews, N.C., dating from the late 19th Century. Matthews was originally known as “Stumptown,” for the many stumps left by farmers as they cleared the land to build houses and fields. In 1872 the Carolina Central Railroad, as it completed its line from Wilmington, North Carolina to Charlotte, located a depot beside a stagecoach stop in Stumptown. Seven years later, in 1879, the town of Matthews was incorporated. It was named after Watson Matthews, a member of the Board of Directors of the Central Carolina Railroad. Beginning in the 1890’s, Trade Street began to develop into a bustling center for commerce frequented by local farmers and the passengers and crews of the many trains that stopped there daily.

| The house had a wraparound shed porch |

Though local lore credits the house with being built in 1845 by W.W. Orr, it is more likely that the structure was erected soon after 1880. It was then that E. J. Funderburk sold the lot on which the house rests to Dr. Henry V. Massey, a medical doctor and Civil War veteran.[1] Funderburk, a prominent farmer, most likely theretofore used the land for growing crops.[2] The home remained in the Massey family until 1925. It was then that Dr. Massey’s children, Daisy Massey Alexander and Henry Massey,[3] sold the house to C.C. (Clarence Coatsworth) Clark and his wife Susie Elmore Clark.[4] Mr. Clark was employed by the Southern Railroad as a section foreman. The couple had five children Paul, Ralph, Ruth, and Helen, who died tragically as a young child of 4 or 5, and an infant who died shortly after birth.[5] When the Clarks lived in the home Matthews was still very rural, and a field next door to the house was used to grow cotton.[6] Later, in 1950, the Matthews Town Hall was erected next door at 224 North Trade Street.

| Clarence Clark |

| Susie Elmore Clark

|

| Paul and Lucy Clark |

In 1953, Paul Clark, his wife Lucy, and their children, Jane and Oliver, came to live with the aging Susie shortly before her death. Jane recounts that while her grandmother was alive, her family used one side of the house and her grandmother the other. Susie had her own living room, to the left of the entrance, and Jane’s family had their own across the hall. Both families had their own kitchens at the back of the house, though everyone ate meals together in her Susie’s kitchen. When Susie died, Paul and Lucy removed the second kitchen and put in the bathroom.

| Clarence Clark Showing Wraparound Porch In Background |

Paul Clark was employed by Williams and Shelton, a wholesale distributor on South Boulevard that sold wares to dry goods stores in Charlotte and its environs. There he managed the Men & Boys Department. Jane remembers that when she was growing up the house was always full of visitors, because it was located so near to Town Hall and people often stopped in. Neighborhood children also frequently ran in and out of the house, the doors of which were never locked. Mrs. Clark was well known for the Raggedy Anne dolls that she made and gave out to children in the community. Jane Clark lived in the house until she left for college. After studying at Emory University, Clark stayed in Atlanta where she became a nurse and received her doctorate. When her parents died Dr. Clark put the house on the market. Concerned that the house would be razed for development she sold the house to the Town of Matthews in 1977.[7]

Beginning in November 1979 the Massey-Clark House was occupied by the Matthews Help Center. The Help Center provided the community an array of services from the small six-room home, including tutoring for students, a thrift store that provided inexpensive used clothing, helping the elderly in filling out tax and social service forms, and providing emergency funds for Matthews families in need. The center was staffed by members of the Matthews Woman’s Club, Matthews Ministerial Association, and other community volunteers. The founders hoped that the center would make services more accessible to the residents of Matthews, who traveled into Charlotte for such assistance before the opening of Help.[8] Joan Uhrich, who has worked for Help for 25 years, credits the house and its architecture with creating a nurturing environment for the organization. She explains that the staff, volunteers, and clients all believed that the offices felt “like home;” providing care was easy in such an environment, Uhrich related.[9] In recent years a retail store occupied the Massey-Clark House. The house presently has no tenant, and the Town of Matthews is seeking a preservation solution for the property.

Architectural Description:

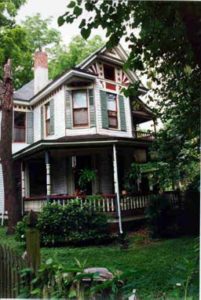

The Massey-Clark House was most likely originally built in the hall-and-parlor form. This type of house is characterized as being two rooms wide and one room deep. Virginia and Lee McAlester write that this type of house “remained the dominant folk housing over much of the rural Southeast until well into the 20th century.”[10] The house is presently cross-gabled, by a later addition. The back side of the house also has a shed addition, adjacent to the earlier addition. The house is located on a small lot on North Trade Street, a busy thoroughfare in Matthews.

The front of the house is three bays wide. Six over six double-hung sash windows are found on either side of the front door. The front door is wood paneled with a six-pane inset window and is flanked by three pane side lights The front stoop is a concrete slab set on a low brick. A 1979 photo shows that the stoop was originally accessed by brick steps; it is now reached by a concrete ramp, to allow for handicap access. Iron rails flank the ramp. The small gabled front porch is covered by a low-pitched roof supported by two posts. Green tar shingles cover the building’s roof. .

Side Elevation

Immediately inside the front door is the central hall. This approximately 11’ by 4’ space is lined on three walls by shelving, added by Help. To the right of the entrance is a small room (approximately 11 foot square). The room contains a non-working fireplace, with a wood mantle. A walk-in closet is accessed through a door in the same wall. Both the ceiling and walls are covered with beadboard. A carpet is laid over the floors, which are likely hardwood like many other rooms in the house. At one time this was a bedroom for room for Paul and Lucy Clark. The room was used by the Help center initially as a meeting room and later as an office and staging area for organizing in-home meal deliveries.

The room to the left of the entrance is a little larger in size, it also has a fireplace on its most rear wall. The fireplace surround is of a pale brick with a wood mantle painted white. The floor is also covered with carpet. The ceiling is covered with a textured spray on application. There is a ceiling fan with light fixture in the ceiling. The rest of the house is lit by industrial neon lighting. This room served C.C. and Susie Clark as a living room, and later as a checkout area for the Help organization’s thrift store.

Rear Elevation

Behind the front two rooms, is the dwelling’s most substantial addition. The first two rooms both have wood floors and one six over six double-hung sash window. They are connected by a small hallway. To the rear of these rooms is the home’s kitchen. The kitchen has painted wood cabinetry, and light beige wood paneled walls. Over the sink, located on the rearmost wall of the house, is a single fixed-pane window. Joan Uhrich, relates that the kitchen served many purposes for the organization, serving both as a food preparation area, place to consume meals, and as a work area.

Interior

A shed-roofed addition was added adjacent to the kitchen. This addition contains a bathroom, back hall, and storage area. The bathroom has a glass paneled door that leads to the front hall. Jane Clark recalls that the bathroom was added when she was a small child in the 1950’s, which accounts for the door which originally led outside. Until then the property had an outhouse. The bathroom floor is linoleum, as is that of the kitchen, back hall, and storage space. The back hall area’s walls are wood clapboard and six over six sash window opens from the kitchen, showing that the space was added to the house.

[1] Mecklenburg County Deed Book, 45, page 211, March 10, 1880.

[2] Born on July 1, 1836, Funderburk was reared near the Lynches River in Chesterfield County, South Carolina. He had migrated to Mecklenburg County soon after the end of the Civil War, a conflict in which he served the Confederacy. Dan L. Morill, “Survey and Research Report, The Funderburk Brothers Buildings,” for the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission

[3] Henry Massey was married to Mamie Renfrow Massey, the daughter of local dry goods merchant T.J. Renfrow. From interview with Mary Louis Phillips, March 3, 2006.

[4] Mecklenburg County Deed Book 585, page 171, April 8, 1925.

[5] Interview with Jane Clark, May 8, 2006. Interview with Tony Clark, May 8, 2006.

[6] Paula Hartill Lester, Discover Matthews: From Cotton to Corporate (Charlotte: Herff Jones Publishing Company, 1999), p. 38.

[7] Interview with Jane Clark, March 10, 2006.

[8] “Help Center Opens Saturday,” Southeast News, November 7, 1979 and Cheryl Mattox Berry, Charlotte News, “There’s HELP in Matthews for those who need it,” April 16, 1979.

[9] Interview with Joan Uhrich, March 2006.

[10] Virginia and Lee McAlester, A Field Guide to American Houses (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1984), Page 94.