Survey and Research Report

for

The Torrence-Lytle School

Click Here to view the Torrence-Lytle Survey and Research Report – torrence-lytle-sr

Survey and Research Report

for

The Torrence-Lytle School

Click Here to view the Torrence-Lytle Survey and Research Report – torrence-lytle-sr

WILLIAM TRELOAR HOUSE

This report was written on July 3, 1984

1. Name and location of the property: The property known as the William Treloar House is located at 328 N. Brevard St. in Charlotte, NC.

2. Name, address and telephone number of the present owner of the property:

Dora M. Dellinger (Mrs. S. W.)

1127 Balling Rd.

Charlotte, NC 28207

Telephone: (704) 375-4628

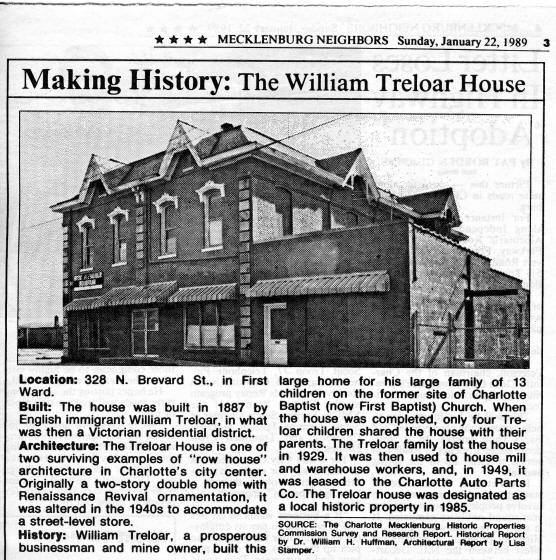

3. Representative photographs of the property: This report contains representative photographs of the property.

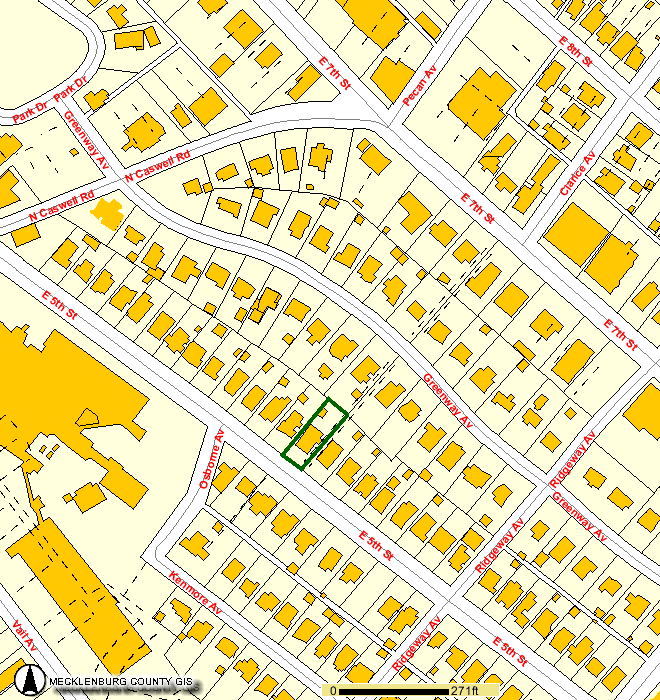

4. A map depicting the location of the property: This report contains a map which depicts the location of the property.

5. Current Deed Book Reference to the property: The most recent conveyance of this property was accomplished by will, not a deed. The Tax Parcel Number of the property is: 080-051-16.

6. A brief historical sketch of the property: This report contains a brief historical sketch of the property prepared by Dr. William H. Huffman, Ph.D.

7. A brief architectural description of the property: This report contains an architectural description of the property prepared by Ms. Lisa A. Stamper.

8. Documentation of why and in what ways the property meets the criteria set forth in N.C.G.S. 160A-399.4:

a. Special significance in terms of its history, architecture, and/or cultural importance: The Commission judges that the property known as the William Treloar House does possess special significance in terms of Charlotte-Mecklenburg. The Commission bases its judgment on the following considerations: 1) the original owner, William Treloar (1825-1894), a native of Cornwall, England, and, therefore, initially attracted to this region because of the gold mines, established himself as a leading businessman of this community; 2) the Treloar House is a rare remnant of the Old First Ward neighborhood; and 3) the Treloar House is one of only two examples of “row house” architecture that survive in the central business district of Charlotte.

b. Integrity of design, setting, workmanship, materials, feeling, and/or association: The Commission contends that the attached architectural description by Ms. Lisa A. Stamper demonstrates that the William Treloar House meets this criterion.

9. Ad Valorem Tax Appraisal: The Commission is aware that designation would allow the owner to apply for an automatic deferral of 50% of the Ad Valorem taxes on all or any portion of the property which becomes “historic property.” The current appraised value of the .295 acres of land is $25,740. The current appraised value of the improvements is $54,420. The total current appraised value is $80,160. The property is zoned B3.

Date of Preparation of this Report: July 3, 1984

Prepared by: Dr. Dan L. Morrill

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Properties Commission

1225 S. Caldwell St.

Charlotte, NC 28203

Historical Overview

Dr. William H. Huffman

The legacy of William Treloar (1825-1894) to Charlotte’s First Ward is the home he built for his family at the southeastern corner of Brevard and Seventh Streets. It is a distinct reflection of the prosperity and expansiveness of the life of the English native, and shows as well the taste and style of a very rare large house surviving from the 1880’s in the area.

Born in Cornwall, England, Mr. Treloar emigrated to the United States in 1844 at the age of nineteen. His port of arrival was Charleston, but after a brief stay he came to Stanly County, where he engaged in mining. About a year later, July 10, 1845, he was married to a native of the county who was born near New London, Julia Franklin Crowell (1829-1906). At this time, the gold mines of this area were quite active, and William Treloar eventually acquired interests in Gold Hill, Rowan County, Pioneer Mills in Cabarrus, and the Ray Mine in Mecklenburg. In addition to these interests, he also conducted a general merchandising business in Salisbury, then in Charlotte.

After moving to Charlotte in the 1850’s, the very successful entrepreneur acquired the Central Hotel, one of Charlotte’s largest, on the first block of South Tryon Street. He also owned the row of store buildings just opposite, which used to be known as Granite Row, and were, in the 1850’s and early 1860’s, called Treloar’s Hall. When the Civil War broke out, Treloar sold the Central Hotel to Miles Wriston, and Granite Row to the Rock Island Company, packed up his family and moved north to Philadelphia, where he went into the boot and shoe business. This was another line of business he had pursued both in Charlotte and Salisbury.

About sixteen years after the end of the war, in 1881 or 1882, the Treloars returned to the South, where William again became interested in mining in Cabarrus County. Five years later, they returned to Charlotte, where they decided to build a large home on North Brevard Street.1 Thus February 13, 1886, a lot for that purpose was purchased in Julia F. Treloar’s name from the Trustees of the Charlotte Baptist Church at the southeast corner of Brevard and Seventh Streets. It was common practice for businessmen to have their residence property in their wives’ names, presumably to protect it from foreclosure due to business losses. The site had been occupied by the Charlotte Baptist Church, now First Baptist.

The Treloars built their large house, which was completed about 1887, to accommodate any of their thirteen children and their spouses who cared to live with them, as well as to be a place fit to show Mr. Treloar’s success in the world. From the City Directories, however, it appears that only four or the children and one husband shared the house with William and Julia Treloar, the rest having married and moved to other parts of the country.

In 1894, at the age of sixty-nine, William Treloar died after a brief bout with pneumonia. His widow Julia remained in the house with an invalid son, Benjamin Franklin Treloar (1859-1908), daughters Louisa Treloar and Julia Treloar Smith (1861-1951), and son-in-law John R. Smith, a traveling salesman. The next year after her husband’s death, Mrs. Treloar deeded the northern side of the house and that half of the corner property to her daughter, Julia Treloar Smith (the property line went through the middle of a brick wall dividing the two sides), for her exclusive use.5

At her own death in 1906, Mrs. Treloar willed the remaining half of the house and property to her children in common, but it was to be kept for the exclusive use of Benjamin Franklin Treloar while he lived.6 Two years later, in 1908, B. F. Treloar died, and the following year, Julia Treloar Smith petitioned the Superior Court to be permitted, as executrix of her mother’s estate, to sell the southern portion of the property to pay expenses, and divide the rest among the heirs. Thus on November 12, 1909, Samuel Lawson Smith (1867-1937), who was apparently not related to John R. Smith, bought the southern half of the house and lot at a court house auction for $4625.50.8 A year and a half later, in 1911, S. L. Smith sold his part of the property to Julia Treloar Smith, who now had possession of both sides of the double house and all the lot. This did not end Samuel Smith’s association with the Treloar house, however, because shortly afterward he married Julia Treloar Smith, whose husband had left a number of years earlier.10

S. L. Smith, a cotton broker and secretary-treasurer of the Merchant and Farmer’s Bonded Warehouse, and his wife Julia occupied the house through the remainder of the Teens, the Twenties and into the early Thirties. Unfortunately, the disastrous effects of the Great Depression caused them to lose the family home, for in January, 1929, they mortgaged the house for five thousand dollars, presumably for business capital, and in September, 1934, the house was sold to W. O. and Ilse Potter on a foreclosure sale.12 For the next thirteen years, the house was rented to various tenants, many of them mill and warehouse workers, until it was bought in 1947 by Steve (d. 1969) and Dora Dellinger, who leased it to Charlotte Auto Parts Company until recently.13

Though modified somewhat to accommodate a business, the Treloar house remains an unusual and stately presence in a part of town that has nothing like it in the immediate area, which is now mostly parking and warehouses. It is a distinct reminder of an era now long past by a hundred years, but it should continue to be a vital part of First Ward in the city, linking future development with a sense of where we have been.

NOTES

1 Charlotte News, January 16, 1894, p. 1; Charlotte Observer, January 17, 1894, p.3; Ibid., November 19, 1906, p.7.

2 Deed Book 60, p.317, 13 February 1886, $2500.00.

3 See note 1; Charlotte City Directories, 1889-1906.

4 Ibid.

5 Deed Book 104, p.592, 18 June 1895.

6 Will Book O, p.500, probated 6 December 1909.

7 Orders and Decrees, Book 13, p.563, 19 May 1909.

8 Deed Book 254, p.570, 3 December 1909.

9 Deed Book 276, p.220, 5 May 1911.

10 Charlotte City Directories, 1912-1935; see note 7.

11 Ibid.

12 Deed Book 733, p.l88, 5 January 1929; Deed Book 858, p.83, 15 September 1934.

13 Charlotte City Directories, 1935-1975; Deed Book 1228, p.23, 7 January 1947.

Architectural Description

Lisa A. Stamper

Located on the southern corner of Seventh and N. Brevard Streets, the Treloar House is one of only two surviving examples of “row house” architecture in Charlotte’s central city. Built in c. 1887 of brick, wood, and stone, it is one of the ten surviving homes in what was once a fine Victorian residential district street. This Victorian two-story double home exhibits beautiful Renaissance Revival ornamentation. Much of the Victorian character of the home is still present despite a first-level storefront placed in the front facade in the late 1940s.

The Treloar House is a rectangular building with a steep-sided mansard roof with small decorative gables. Beautiful decorative slate roofing is found on the majority of the mansard roof. The shallow sloped top portion is not intended to be seen, therefore, less expensive roofing material is found on that portion. The gables are complete with pendanted collar braces and decorated collar beams. The prominent eaves of the roof are molded. On the rear side of the roof a metal addition was placed on the tripped part of the roof. Two chimneys on the rear of the roof are side by side, one of which continues down the exterior of the basic facade. On the top of the roof, fancy ventilators longitudinally flank a central flagpole.

The dual-residential nature of the original building was emphasized in the building’s front facade. Rusticated stone blocks were placed vertically in the brick pilasters on both ends of the facade. Another pilaster with identical stone block decoration was located directly in the middle of the facade, dividing it visually into two units. Eighteen blocks started at the ground level and continued up to brick corbelling not far below the eaves. The bottom portion of the middle pilaster was taken out to accommodate the mid-twentieth century storefront, leaving only seven blocks. The middle pilaster had two ornate brackets between the corbelling and the eaves. It is likely that identical brackets were also present on the corner pilasters. The stone blocks, plus the appearance of two identical houses placed side by side gave the house a very strong vertical feeling, which was a common Victorian feature.

Evidence of four-arched openings in the front facade can be seen upon close inspection of the storefront. Four arches can be seen above it as well as where the symmetrically placed openings have been bricked up. Today the storefront has a central double door. Flanking this door are two large, three-sectioned windows. Two concrete steps lead up to the doorway. Metal awnings cover the windows and door.

The upper level windows of the front facade reflect the Renaissance Revival styles. There exist four symmetrically-placed windows on the second-floor; two windows are placed on each side of the center pilaster. They are tall and thin double-hung windows with simple sills and elaborate cast iron Italianate window heads in excellent condition. One small squarish window is located under each front facade gable. These also have simple sills and are a common feature of the Renaissance Revival.

Both the northeast and the southwest sides of the Treloar House were identical. Presently, an addition covers much of the first-level on the southwest facade. A wooden second-level rectangular bay window is located underneath each gable closest to the back-end of the house. Each bay window has Stick Style trim with X braces plus diagonal and vertical siding. Each also as three windows, one facing the front and one facing each side. They are arched windows made of wood with glass in the upper half only.

On the Seventh Street side there are a total of eleven slightly-arched windows (not including the bay window). Six windows are located on the first-level and five are on the second-level. All these windows are bricked sills except for the first-level window nearest to the front, which has a concrete sill. On the first-level, all the windows are bricked up except for the first-level window nearest to the front. On the second level, the window nearest to the backend is about one-half the size of the others and has a more rounded arch. Although not all are of the same shape nor symmetrically placed, the windows are definitely ordered The first four second-story windows from the front are lined up with the first four first-story windows. The other two first-story windows are placed under the bay window. The narrowest second-level window is placed near the back-end of the house. Two-course brick corbelling runs along arches over the window openings. The corbelling appears to continue behind the bay window and along the back-end of the house.

The rear of the house is difficult to see since another addition was placed on the back and other stores were added on adjacent lots. The rear of the house is almost totally blocked from view by a rear addition and stores built on adjacent lots. The back facade contains two slightly arched second-level windows which are considerably smaller than most of the other windows. A long, rectangular sign is located under the corbelling along the back and also cuts across the windows.

The two commercial additions are of brick and concrete blocks and are one-story high. They are rectangular in shape with flat roofs. One was built on the southwest side of the house and the other was added onto the rear. The sides of the additions which face the streets are constructed with brick while the rest of the structures are mace with concrete blocks. The southwest side addition was built as a separate store and has its own door, window, and metal awning. From the late 1940s to the late 1970s the Charlotte Auto Parts Co. used the house as a store and the side addition as a machine shop. It appears as if the addition to the rear of the house was built to expand the building for warehouse storage use. The present use for the house is storage for two different companies.

The Treloar House appears to have been painted at one time. The woodwork at the gables arch eaves, the ornamental winding heads, and the window sills have been painted white. The brickwork and additions were painted brick red. The stone blocks of the front facade were left natural.

An interior wall about the same thickness as the exterior walls was removed to make room for the storefront and business. This wall divided the house into two identical homes. According to the present owner, Mrs. S. W. Dellinger, other major changes have been made to the interior.

The area containing the Treloar House is now zoned for commercial use. Charlotte historian Mary Pratt has found evidence that Brevard Street was once a highly respected residential street. The Treloar double home is two blocks from prestigious Old First Baptist Church (now Spirit Square) and an easy walk from the central business district. Today the area is composed of mostly vacant lots and a few commercial and warehouse buildings. The Treloar House is one of only three houses left on Brevard Street today. The recent renovations of Spirit Square, First United Presbyterian Church along with the proposed rehabilitation of the Philip Carey Warehouse and the Old Little Rock AME Zion Church Afro-American Cultural Center all nearby on Seventh Street, may stimulate reuse of this important reminder of Charlotte’s Victorian residential past.

TROLLEY WALK

This report was written on January 10, 1993

1. Name and location of the property: The property known as the Trolley Walk connects East Fifth Street and East Seventh Street, at the junction of Clarice Avenue and Seventh Street, in the Elizabeth neighborhood of Charlotte, Mecklenburg County, North Carolina.

2. Name, address, and telephone number of the present owner of the properties. The owners of the property are:

William G. Staton

2113 East Fifth Street

Charlotte, North Carolina 28204 (Tax Parcel Number 127-047-16)

Lynn Andrew Teague and William Henry Curtis

2117 East Fifth Street

Charlotte, North Carolina 28204

(Tax Parcel Number 127-047-17)

Ellen Rubenstein

2062 Greenway Avenue

Charlotte, North Carolina 28204

(Tax Parcel Number 127-047-31)

Baxter T. McRae, Jr.

2100 Greenway Avenue

Charlotte, North Carolina 28204

(Tax Parcel Number 127-047-30)

Jacqueline Levister

2061 Greenway Avenue

Charlotte, North Carolina 28204

(Tax Parcel Number 127-046-15)

G. Howard Webb

1300 Queens Road

Apartment 418

Charlotte, North Carolina 28207

(2101 Greenway Avenue)

(Tax Parcel Number 127-046-16)

D.P.R. Associates

2036 East Seventh Street

Charlotte, North Carolina 28204

(Tax Parcel Number 127-046-26)

K & C Investments

131 Providence Road

Charlotte, North Carolina 28207

(2100 East Seventh Street)

(Tax Parcel Number 127-046-25)

3. Representative photographs of the property: This report contains representative photographs of the property.

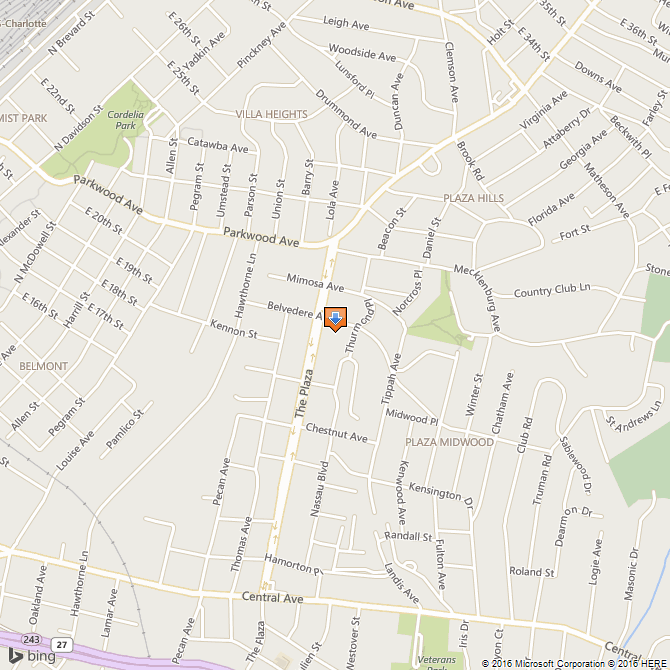

4. Maps depicting the location of the property: This report contains maps which depict the location of the property.

5. Current deed book references to the properties: There is no tax parcel number for the Trolley Walk, which is owned by all adjacent property owners. Tax Parcel Number 127-047-16 is listed in Mecklenburg County Deed Book 6819 at page 151. Tax Parcel Number 127-047-17 is listed in Mecklenburg County Deed Book 4022 at page 520. Tax Parcel Number 127-047-31 is listed in Mecklenburg County Deed Book 5608 at page 368. Tax Parcel Number 127-04730 is listed in Mecklenburg County Deed Book 7221 at page 345. Tax Parcel Number 127-046-15 is listed in Mecklenburg County Deed Book 4030 at page 148. Tax Parcel Number 127-046-16 is listed in Mecklenburg County Deed Book 3115 at page 459. Tax Parcel Number 127-046-26 is listed in Mecklenburg County Deed Book 4365 at page 489. Tax Parcel Number 127-046-25 is listed in Mecklenburg County Deed Book 4593 at page 689.

6. A brief historical sketch of the property: This report contains a brief historical sketch of the property prepared by Frances P. Alexander.

7. A brief architectural description of the property: This report contains brief architectural description of the property prepared by Frances P. Alexander.

8. Documentation of why and in what ways the properties meet criteria for designation set forth in N.C.G.S. 160A-400.5:

a. Special significance in terms of history, architecture, and cultural importance: The Commission judges that the property known as the Trolley Walk property does possess special significance in terms of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County. The Commission bases its judgement on the following considerations: 1) the Trolley Walk was designed ca. 1913 and is one of the original features of the Rosemont subdivision of Elizabeth; 2) the Trolley Walk is one of the few remnants of the streetcar system which spurred suburban development in Charlotte during the early twentieth century; and 3) the walk, with the surrounding early twentieth century housing, clearly illustrate such residential development in the early streetcar suburbs.

b. Integrity of design, setting, workmanship, materials, feeling, and association: The Commission contends that the architectural description by Frances P. Alexander included in this report demonstrates that the Trolley Walk property meet this criterion.

9. Ad Valorem Tax Appraisal: The Commission is aware that designation would allow the owners to apply for an automatic deferral of 50% of the Ad Valorem taxes on all or any portion of the properties which become designated historic landmarks. The current appraised value of the improvements to the Trolley Walk and adjacent properties is $471,410.00. The current appraised value of the Trolley Walk and adjacent properties, Tax Parcel Numbers 127-04716; 127-047-17; 127-047-31; 127-047-30; 127-04-15; 127-046-16; 127-04-26; and 127-046-25, is $626,280.00. The total appraised value of the Trolley Walk and adjacent properties is $1,097,690.00. Tax Parcel Numbers 127-047-16; 127-04717; 127-047-31; 127-047-30; 127-046-15; 127-046-16 are zoned R5. Tax Parcel Numbers 127-046-26 and 127-046-25 are zoned 02.

Date of Preparation of this Report: January 10, 1993

Prepared by: Frances P. Alexander, M.A.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission

P.O. Box 35434

Charlotte, North Carolina 28235

(704) 376-9115

Architectural Description

Location and Site Description

The Trolley Walk is located in the Elizabeth neighborhood, an early twentieth century streetcar suburb, of Charlotte, North Carolina. Specifically, the Trolley Walk extends from the west side of East Seventh Street, at the point where Clarice Avenue and East Seventh Street meet, through the middle of the block to Greenway Avenue. From the west side of Greenway Avenue, the walk runs to the east side of East Fifth Street where the path terminates. Along its course, the trolley walk is bounded by early twentieth century residential development, including apartment houses, two-unit dwellings, and single family houses. The proposed designation includes the walkway between East Fifth Street and East Seventh Street.

Architectural Description

The Trolley Walk is a sidewalk, constructed of concrete slabs, which is wide enough to accommodate two lanes of pedestrian traffic. Extending through the center of two city blocks, the walkway is on grade for most of its route, connecting with the public sidewalks along East Seventh Street and Greenway Avenue. However, the walkway ends at concrete steps which lead down to the public sidewalk at East Fifth Street. The Trolley Walk is bordered by residential properties. Two adjoining properties, an apartment house on Seventh Street and a two-unit house on Greenway Avenue, have walkways which connect with the Trolley Walk. In other sections of its path, the Trolley Walk is hedge-lined.

Historical Overview

The Trolley Walk was constructed in the Elizabeth neighborhood, an early streetcar suburb in Charlotte. Elizabeth was developed quickly, but incrementally, in five stages. The first development in Elizabeth was Highland Park, begun in 1891 by the realty company associated with the Highland Mills. Highland Park was located along Elizabeth Avenue, the eastern extension of East Trade Street, near the present location of Central Piedmont Community College. In 1897, the Highland Park Land Company, under the direction of Walter S. Alexander, donated land for a Lutheran College, named Elizabeth College, and the surrounding area soon became known as Elizabeth Hill. At the same time, Elizabeth Avenue was platted as a boulevard, and five years later, in 1903, the East Trade Street electric streetcar line was extended to the college. Begun in 1887, horsedrawn and muledrawn streetcar service in Charlotte already included an established route to what was then the future location of Elizabeth College from West Trade Street at the Richmond and Danville Railway, later the Southern Railway, crossing. The electric trolley network, which began service in March 1891, was expanded over the next 25 years, and by 1903 reached Elizabeth College (Blythe and Brockmann 1961: 264). With the extension of streetcar lines along Elizabeth Avenue, Hawthorne Lane, and Seventh Street, residential subdivision activity quickly followed as reliable and frequent streetcar service provided easy access to the commercial and business centers downtown. By 1907, the boundaries of the city were expanded to include the early rings of suburban development found in Highland Park to the southeast and Dilworth to the south (Hanchett 1984: 7).

In 1900, Piedmont Park, between Central Avenue and Seventh Street, was platted as the second subdivision within the Elizabeth neighborhood. By 1903, Oakhurst, which straddled the main line of the Southern Railroad in the vicinity of the Plaza, Hawthorne Lane, and Central Avenue, was developed to encompass both factory sites as well as residential properties. With trolley service from downtown along Central Avenue and the northern section of Hawthorne Lane through Villa Heights, Central Avenue quickly became a fashionable address. The fourth subdivision within Elizabeth, Elizabeth Heights, was centered around Independence Park, which was built beginning in 1904 as the first municipal public park. Construction in Elizabeth Heights began in 1904 and also included the area between Seventh Street and the present Seaboard Railroad, which had streetcar access along Seventh Street.

The Trolley Walk was built in the Rosemont subdivision, the final phase of construction in Elizabeth and the area farthest from the downtown business district. Rosemont was platted on the former Henry C. Dotger farm which extended roughly from Caswell Road to Briar Creek. Development plans were begun in 1913 for what was initially called Dotger Estates, or alternately, the Pines (Hanchett 1984: 20). The Trolley Walk appears to have been a unique feature of the initial plan (ca. 1913), and the developer intended the Trolley Walk to be a publicly owned right-of-way. However, the city never accepted ownership, and the walk is now owned by adjacent property owners (Pressley 1993). In 1915, Dotger sold his farmland to the newly formed Rosemont Company, comprised of George Watts and Gilbert White of Durham and C.B. Bryant, W.S. Lee, Z.V. Taylor, E.C. Marshall, and Cameron Morrison of Charlotte. The following year, the company hired noted planner, John Nolen of Boston, to design Rosemont. However, little of Nolen’s plan for the new subdivision was implemented. In 1918, Gilbert White had sold his portion of the company to Charlotte real estate agent, E.C. Griffith, who also developed Wesley Heights, the west side residential neighborhood, the West Morehead Street industrial district, and Eastover, an affluent suburb on the east side of Charlotte (Blythe and Brockmann 1961: 173). Griffith was largely responsible for the abandonment of Nolen’s plan, evidently for economic reasons. The curvilinear streets proposed by Nolen created oddly configured lots and increased the costs of surveying (Hanchett 1984: 21). As a result, most of the streets of Rosemont were platted in a conventional grid pattern although East Fifth Street followed a curve so as to meet East Seventh Street, one feature of Nolen’s design.

As the name suggests, streetcar suburban development was, in large measure, determined by the routes of the street rail systems (Warner 1978: 46-65). These transportation networks allowed residential development beyond the historical confines of city cores. Prior to the initiation of rapid and frequent street rail service, development had been limited by the distances people could walk from home to places of businesses and commercial activity. Streetcar service created development opportunities, and as Elizabeth illustrates, residential construction for both the wealthy and the middle class usually followed the extension of routes rather quickly.

The geography of streetcar suburbs generally followed similar patterns. In contrast to the automobile-oriented suburbs of the post-World War II era, the streets along which the trolleys ran were often laid out as grand avenues or boulevards and became prime residential locations for the wealthy. During the early years of the twentieth century, this pattern held true in Elizabeth, and many of the elite of Charlotte built impressive houses along Elizabeth Avenue in Highland Park, Hawthorne Lane in Elizabeth Heights, Central Avenue in Piedmont Park. Now associated with heavy traffic and noise, the wide streets served by the trolleys were desirable precisely because of their proximity to the street rail lines. As grand houses were built on the streetcar boulevards, the side streets, farther from trolley paths, were developed for the middle class. Property values and development potential were inextricably tied to the location of this fixed system of trolleys, and areas, located several blocks from the streetcar line, would command lower prices than properties situated directly on the trolley route. Thus, development patterns in streetcar suburbs were less economically segregated than later automobile suburbs, with housing for the middle class, the wealthy, and sometimes the working class, often found within one suburb although development and property values were determined by proximity to the streetcar route (Warner 1978: 65).

The construction of a walkway, such as the Trolley Walk, at the terminus of the streetcar line was designed to make side street property more valuable than it ordinarily would have been. By designing a public pathway, the developers sought to make Fifth Street lots almost as desirable as Seventh Street, along which the trolleys ran. Indeed, in a 1923 advertising pamphlet for Rosemont, Fifth Street lots sold for $1500.00 while Seventh Street property was valued at $2500.00 per lot, which underscores the role of the streetcar in determining land values (Hanchett 1984: 22). Although the Trolley Walk is not solely responsible, it is clear that the houses found on Fifth Street do not differ substantially from Greenway Avenue and Seventh Street and that Rosemont is more thoroughly middle class than earlier subdivisions of Elizabeth. Developed primarily in the 1920s, Rosemont also reflects the explosion in automobile ownership which occurred after World War 1. Throughout the interwar era, expanding automobile use gradually, but effectively, eliminated dependence on streetcars for inter-city transportation. Consequently, residential development patterns changed with the shift in transportation. Particularly for the affluent, automobiles allowed greater freedom in location. With the weakening of fixed transportation routes, residential development became more segregated by income, and suburbanization became more fluid and far-flung. Nonetheless, streetcar service during the 1920s was still necessary for the working and middle classes and continued to play a role in suburban development. Rosemont, as an area of bungalows, small Tudor Revival cottages, duplexes, and small apartment houses strongly reflected this increasingly homogeneous composition as well as a continued reliance on trolley service.

By the late 1930s, however, streetcar use had declined significantly, and Duke Power Company, which owned the electric street rail system ended operations. By the 1950s, the main boulevards, once some of the most valuable residential real estate in Charlotte, had become undesirable because of noise and congestion. Streetcar routes shifted from residential to commercial use in many cases, and demolition, because of zoning, became commonplace. Indeed, the 1960 master plan for Charlotte slated one-half of Elizabeth for razing (Hanchett 1984: 29). In Elizabeth, the changes in transportation and land use patterns has greatly altered the characteristic streetcar suburban patterns, particularly as institutions, such as hospitals and Central Piedmont Community College, now occupy vast areas of the neighborhood. Consequently, elements such as the Trolley Walk remain as one of the few vestiges of the streetcar system that defined the nature of early twentieth century suburban development.

Conclusion

The Trolley Walk specifically illustrates the importance of the streetcars in determining residential development patterns in the early twentieth century. By constructing this walkway from the terminus of the Elizabeth Avenue-Hawthorne Lane-Seventh Street streetcar line at Clarice Avenue, all the lots in the new subdivision of Rosemont were sited within a two block walk of the streetcar. The Trolley Walk thus created higher values for properties not located directly on the streetcar route. In an area which has undergone tremendous alteration, the Trolley Walk, and the early twentieth properties surrounding the pathway, are remarkably intact and vividly illustrate early twentieth century, middle class, suburban construction.

Bibliography

Bishir, Catherine. North Carolina Architecture. Chapel Hill: University, of North Carolina Press, 1990.

Blythe, LeGette and Charles Raven Brockmann. Hornets’ Nest: The Story of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County. Charlotte: McNally of Charlotte, 1961.

Hanchett, Thomas W. Charlotte Neighborhood Surveys: An Architectural Inventory. Volume III: Cherry, Elizabeth, Crescent Heights, and Plaza Midwood. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Properties Commission, November 1984.

Pressley, R.N., Jr., P.E., Director, Charlotte Department of Transportation. Letter to Frances P. Alexander, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission, March 11, 1993.

Sanborn Fire Insurance Company. Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1929, and 1953.

Warner, Sam Bass, Jr. Streetcar Suburbs. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1978.

The VanLandingham Estate

Original Report Prepared July 5, 1977

Updated August, 1997

1. Name and location of the property: The property known as the VanLandingham Estate is located at 2010 The Plaza in Charlotte, N.C.

2. Name, address, and telephone number of the present owner and occupant of the property:

The present owner of the property is: Mr. And Mrs. Mark Gilleskie

2010 The Plaza

Charlotte, N.C. 28205

Telephone (704) 334-8909

3. Representative photographs of the property: This report contains representative photographs of the property.

4. A map depicting the location of the property: This report contains a map depicting the location of the property.

5. Current Deed Book Reference to the Property: The most recent reference to this property is found in Mecklenburg County Deed Book 5529 at Page 0824. The Parcel Number of the Property is 095-061-01A & 095-061-01B.

6. A brief historical sketch of the property:

Susie Harwood VanLandingham, wife of Ralph VanLandingham, purchased lots 6 – 9, located to the immediate southeast of the intersection of Belvedere Ave. and The Plaza, from Chatham Eatates, Inc. on March 13, 1913. The VanLandinghams moved to Charlotte, N.C. from Atlanta, Georgia in 1907. Mr. and Mrs. VanLandingham had initially lived with the former’s parents, John Henry VanLandingham and Mary Oates Spratt VanLandingham, at 500 East Avenue (or E. Trade Street). Mr. VanLandingham had returned to Charlotte to join a cotton brokerage firm headed by his father that would soon move its offices to the eleventh floor of the Realty Building, later known as the Independence Building.

From 1909 until 1914 Mr. and Mrs. VanLandingham lived in a house at the intersection of Central Avenue and Piedmont Street. In May 1913, Mrs.VanLandingham secured a loan of $6000 from the Independence Trust Co. for purposes of erecting a residence on the lots which she had purchased from Chatham Estates, Inc. The VanLandinghams completed and occupied the house, designed by noted Charlotte architect Charles Christian Hook (1870 – 1938), sometime during 1914.

Ralph VanLandingham, born in Charlotte on November 9, 1875, lived in the house on The Plaza until his death on August 3, 1959, although he did spend considerable time at his summer home in Linville, N.C. He succeeded in establishing himself as an affluent cotton broker and prominent citizen in the community. He had an extended tenure as senior warden of St. Peter’s Episcopal Church. For several years he was treasurer of the Charlotte Country Club. Indeed, his civic activities even extended to Linville, N.C., where he served as treasurer and senior warden of All Saints Episcopal Church.

Susie Harwood VanLandingham, born in the late 1860’s in St. Paul, Minnesota, was an outstanding human being. In 1881, she moved with her family to Volusia County, Florida, where her father, Norman B. Harwood, became a high official with the Florida East Coast Railroad then being developed by Henry Morrison Flagler. After her father’s death in 1885, she moved with her mother, Susan Drury Deane Harwood, to Atlanta, Ga. It was here that she would meet Ralph VanLandingham and would become his wife on September 17, 1901. In the intervening years, however, Susie demonstrated that she had acquired considerable executive ability. She was one of the founders of the Atlanta Art Association. She was an officer of the Atlanta Y.M.C.A. Even more significantly, she headed the company which built the first fire-proof hotel in the State of Georgia.

Mrs. VanLandingham continued to be active in civic affairs in the years following her arrival in North Carolina. The Charlotte News characterized her as “a woman of rare gifts and a person of unmistakable quality.” Perhaps the most distinctive characteristic of Mrs. Ralph VanLandingham the newspaper asserted, “was the range and depth of her interests.” She served as regent of the Halifax Convention Chapter, Daughters of the American Revolution. She was Chairman of the North Carolina Board of Approved Schools. She was president of the Board of St. Peter’s Hospital, where she financed the building of the emergency waiting room in honor of her mother. Probably her most notable contribution, for which she received a personal commendation from President Woodrow Wilson, was her supervision of the Red Cross Canteen at Camp Greene during World War I. Finally, Mrs. VanLandingham provided generous support to the Crossnore Industrial School for Mountain Children near Linville, N.C. She died at St. Peter’s Hospital on September 26, 1937.

Mr. and Mrs. VanLandingham had two children: Susan Deane VanLandingham, a nationally known golf star as a young woman, who married Norman Cordon, Jr., and resided in Chapel Hill, N.C.; and Ralph VanLandingham, Jr., a prominent stock broker and bachelor who resided at the house on The Plaza. The children were twins, born in Atlanta, Ga. in 1902. Susan VanLandingham Cordon died in 1964, leaving her interest in the house in Charlotte, N.C. to her daughter, Susie Harwood Cordon.

Ralph VanLandingham, Jr., died on March 30, 1970. Securing sole ownership of the property at 2010 The Plaza on December 27, 1966, he established an arrangement by which the University of North Carolina at Charlotte would obtain the property upon his death. That Mr. VanLandingham decided upon this course of action is not surprising. He had demonstrated his support for UNC-C by establishing the VanLandingham Glen on the campus. This garden received plantings from the lavish rhododendron collection which Mr. VanLandingham had developed in honor of his father on the grounds surrounding the house. Further documenting Mr. VanLandingham’a commitment to education was the fact that he provided scholarships for several students who attended colleges and universities in North Carolina.

7. A brief architectural description of the property: This report contains an architectural description prepared by Jack 0. Boyte, A.I.A.

8. Documentation of why and in what ways the property meets the criteria set forth in N.C.G.S. 160A-399.4:

a. Historical and cultural significance: The VanLandingham Estate is historically and culturally significant for four reasons. First, the structure has architectural significance as a superior example of affluent domestic architecture of the early twentieth century. Second, the interior furnishings are largely in place and are superior in design and form. Third, the grounds contain a magnificent collection of rhododendron and constitute one of the most noteworthy gardens in Charlotte, N.C. Fourth, the properly has associative ties with individuals of local, regional and state-wide importance.

b. Suitability for preservation and restoration: The house and grounds retain their initial integrity and are therefore highly suited for preservation.

c. Cost of acquisition and restoration: At present the Commission has no intention of purchasing this property. It assumes that all costs associated with preserving and maintaining the property will be paid by the owner or subsequent owner of the property.

d. Educational value: The property has educational value because of its historic and cultural significance.

d. Possibilities for adaptive or alternative use of the property: The house and the grounds could be used adaptively for a variety of purposes.

f. Appraisal value: The current tax appraisal of the house and outbuilding is $90,460. The current tax appraisal of the land is $112,790. The total taxable value is $298,800. The Commission is aware that designation of the property as a historic property would allow the owner to apply annually for an automatic deferral of 50% of the rate upon which the Ad Valorem taxes are calculated.

g. The administrative and financial responsibility of any person or organization willing to underwrite all or a portion of such costs: As stated earlier, at present the Commission has no intention of purchasing this property. Furthermore, the Commisson assumes that all costs associated with the property will be met by whatever party now owns or will own the property.

9. Documentation of who and in what ways the property meets the criteria established for listing in the Nationa1 Register of Historic Places: The Commission believes that the property known as the VanLandingham Estate in Charlotte, N.C. does meet the criteria of the National Register of Historic Places. Basic to the Commission’s position is its understanding of the purpose of the National Register. Established in 1966, the National Register represents the decision of the Federal Government to expand its listing of historic properties to include properties of local, regional, and State significance. The Commission believes that the VanLandingham Estate is of local and regional historic significance, and therefore, meets the criteria for listing in the National Register of Historic Places.

10. Documentation of by and in what ways the property is of historic importance to Charlotte and/or Mecklenburg County: The VanLandingham Estate is historically important to Charlotte and Mecklenburg County for four reasons. First, the structure is architecturally significant. Second, the interior furnishings are superior in design and form. Third, the grounds contain one of the more noteworthy gardens in the City and hold a rhododendron collection of major importance. Fourth, the property has associative ties with individuals of local, regional and State-wide significance.

Bibliography

An Inventory of Buildings in Mecklenburg County and Charlotte for the Historic Properties Commission.

Charlotte City Directory (1907, p.434); (1908, p.325); (1909, p.339); (1910, p.359); (1911, p.404); (1912, p.420); (1913, p.425); and (1914, p.487).

Charlotte News (September 24, 1937, p.4 and p.11); (December 26, 1937, Sec. 2, p.1, and p.14.); and March 31, 1970, p. 58).

Estate Records of Mecklenburg County. (Will Book Y, pp.443-446, p. 529)and (Will Book 27, p.428).

Records of the Mecklenburg County Tax Office. Parcel number 095-061-01.

Sanborn Insurance Maps of Charlotte (1911, p.71); (1929, Vol. 2, p.228).

The Charlotte Observer (February 27,1915, p.2); (September 27, 1937, p.1, p.3); (December 26, 1937, Sec. 2, p.1); (August 4, 1959, p. 1B); and (April 1, 1970, p.18A).

Vital Statistics of Mecklenburg County (Death Book 51, p.391).

Date of Preparation of this Report: July 5, 1977

Prepared by: Dr. Dan L. Morrill, Director

Charlotte – Mecklenburg Historic Properties Commission

139 Middleton Drive

Charlotte, N.C. 28207

Telephone: 332-2726

ARCHITECTURAL DESCRIPTION

There was an enormous building boom in the first several decades of our century. More houses were built during those years than ever before in so short a time. Designers and architects created residences which in terms of style pointed everywhere. Inspiration came from Georgian England, Renaissance Italy, Sixteenth Century France and Spain, Colonial and Federal America and elsewhere. But the most universal influences were the bungalow books, the stock ready-to-build houses, and mail order stores. Public tastes were profoundly affected by magazines offering plans for houses designed to improve living accommodations of Americans.

These plans had much of their design origin in the Bengalese ‘bangla’, a low house used by the British in India, which was surrounded by a veranda. Built at intervals along main roads, these bungalows were intended to provide only temporary or seasonal dwellings. But adapted to residences in this country by architects and designers, there was little other than the name that was Indian about the vast majority of bungalows. Designers most often drew from Japanese or Spanish sources. In California, where climate and social conditions were favorable, the bungalow flourished as nowhere else, with the result that ‘California bungalow’ was interchangeable with ‘bungalow’. This style embodied spreading dormers, porch-verandas, lightness of construction, shingled walls, and stone chimneys. Additionally it was the bungalow as much as any other kind of house that led to the general adoption of the living room and the outdoor – indoor living space.

In 1912 Charlotte, a well-to-do cotton broker and his family moved from the older Piedmont Courts section to the new suburban development at the end of the East Charlotte trolley line — Plaza Hills. Here Mr. and Mrs. Ralph VanLandingham commissioned a prominent local architectural team, Hook and Rogers, to design a house in the ‘latest’ style, not dictated by obvious historic precedents. The designers embraced the most popular idiom of the day — California bungalow -and adapted the style to the large VanLandingham house to be located on the many acred country site in Plaza Hills.

Resting solidly on a foundation of random granite ashlar, the expansive two story house is a rare local example of the Bungaloid style adapted to massive proportions — an idea far removed from the style’s simple origins. Having basically a center hall rectangular plan, the structure includes projecting wings on both floors which create asymmetrical exterior facades. Approaching the front entrance a circular carriage drive leads to wide steps which rise some three feet to a broad tiled platform. Over this entrance area is a low roofed canopy supported on stone piers at each side and joined at the front by an arched stone lintel. From the entrance platform, wide terraces extend across the full width of the house and turn down each side to form verandas.

Arched glass doors form the main entrance and lead to a small tile floored vestibule. Beyond this are additional double doors opening to a wide center hall. Decorative millwork is limited to broad, simply molded casing surrounding the two pairs of doors. Elsewhere there is only rectilinear molding and trim, classical molded shapes being noticeably absent.

Exterior design is severe, even stark, and generally exhibits machined woodwork of simple shapes. Wall surfaces are uniformly gray stained cypress shingles laid in alternating wide and narrow bands. Windows are tall double hung units with large single glazed sash in upper and lower panels. Window grouping varies in each bay and reflects directly the wide variations of the plan and room sizes. In no instance is there deliberate effort made to present a symmetrical placement of design elements.

At the roof overhang, exposed rafter ends are sawn in undulating pattern to create a bracketed soffit extending out some three feet from wall surfaces. There is no crown molding or other elaboration at the cornice. Reflecting the wing projections and dormer features, the tall hipped roof presents a variety of shapes. Covered with terra cotta tile, this large roof mass dominates the exterior. Rising here and there from the roof are tall granite chimneys.

At the sides and rear the window placement again reflects plan irregularities. Facing the broad, carefully landscaped grounds to the right(south)side is an expanded circular terrace which opens from the interior through the double glazed doors. Above this terrace is an iron trellis erected to provide support for climbing vines. At this side the double doors are arched, and in one section which connects to a solarium they are surrounded by granite ashlar laid to form a carefully proportioned stone canopy with projecting wood brackets in the arch. On the opposite(north)side the drive is extended to join a service entrance. Here also there is a low roofed canopy supported by granite piers and connected by an arched lintel.

The rear (east) side is the handsomest facade of the house. Featuring an arched, triple unit window which lights and ventilates the large dining room, this side also has two carefully proportioned arched stone encased doorways from the solarium. On the second floor there are wood frames with copper wire panels enclosing sleeping porches adjoining two major bedchambers. Also at the rear a delicate slatted screen conceals a rear service entrance and cellar stair.

Through the main entrance the large foyer is encountered. From this high ceilinged hall, four rooms radiate to the sides and rear. At the front right, double sliding pocket doors open to a large rectangular living room. On the long inside wall a centered fireplace includes an iron coal burning grate and an elaborately carved black marble mantel. Flanking this fireplace are double doors, with multiple glazed lights, opening to a solarium at the rear. Featuring a large stone chimney, also centered on the interior wall, this sun porch is enclosed on two sides by continuous arched windows and glass doors which open to a rear terrace. Finished with rustic simplicity, the solarium has a herringbone brick floor, stained cypress wall shingles, and board and battened painted ceiling.

Again just inside the front entrance, another pair of sliding pocket doors open from the foyer to the left into a book-lined study. Another small fireplace, similar to that in the living room, is centered in the far side wall and features a fine carved, imported marble mantel.

The center hall forms a long axis from front to rear. Terminating at high arched glass doors, the hall leads directly into a dining room of banquet proportions. This room has huge windows on the east and south oriented to exploit the natural beauty of the immense gardens leading away from the house on these two sides.

From the north side of the dining room, doors lead to the pantry and in turn to a large kitchen. Here are early examples of gas and electric services. Also at the rear the center hall turns left to enclose a wide stair leading to the second floor. Rising some fourteen feet in two runs, this broad stair features delicate turned balusters and elaborately carved heavy newel posts hinting of Victorian origins.

On the second floor are four large bedchambers, each with separate baths. These rooms vary considerably inside and the three largest rooms have adjoining sleeping porches or ‘outdoor rooms’ designed for warm weather sleeping. Curiously, these outdoor rooms are floored with canvas.

Interior finishes in the house are uniformly simple. Walls and ceilings are plastered and have little or no molded trim. Chair rails and wainscot paneling are not used. Window and door casing consists of simple rectangular boards with square rabbeted back bands. Flooring throughout is narrow oak strips, with the exception of ceramic tile in the bath rooms.

A visit to the VanLandingham house offers a glimpse into the ‘honest’ woodwork and unpretentious design of the post-Victorian age. Escaping from the staid formalities of Victorian fashion, many designers over reacted with detailing which reflected only the efficient lines of machined wood — leaving little or no evidence of the skill and creativity of earlier wood hand craftsmanship. This imposing house and its marvelous gardens are unique in Charlotte. Not necessarily easy to admire, the strong statement of the design speaks eloquently of the early twentieth century architecture in Charlotte.

Related items…

Survey & Research Report: Carriage House at the VanLandingham Estate