ROBERT J. WALKER HOUSE

This report was written on November 5, 1980

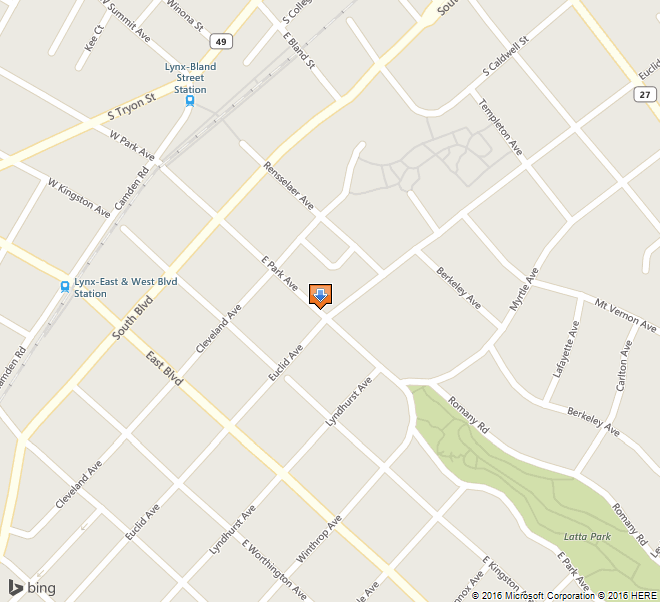

1. Name and location of the property: The property known as the Robert J. Walker House is located at 329 E. Park Ave. in Charlotte, N.C.

2. Name, address and telephone number of the present owner and occupant of the property: The present owner and occupant of the property is:

Kenneth D. Williams, Jr. and wife, Helen C. Williams

329 E. Park Ave.

Charlotte, N.C. 28203

Telephone: (704) 334-4477

3. Representative photographs of the property: This report contains representative photographs of the property.

4. A map depicting the location of the property: This report contains a map which depicts the location of the property.

5. Current Deed Book Reference to the property: The most recent deed on this property is recorded in Mecklenburg County Deed Book 3482 at Page 294. The Tax Parcel Number of the property is 123-071-07.

6. A brief historical sketch of the property:

On June 9, 1901, the Charlotte Observer reported that the architectural firm of Hook and Sawyer was designing several buildings in Charlotte and its environs, including the home of Robert J. Walker in Dilworth, Charlotte’s initial streetcar suburb.1 Charles Christian Hook (1870-1938) and Frank M. Sawyer had established their partnership in October 1898, soon after Sawyer had moved to Charlotte from Anderson, S.C.2 C. C. Hook, a native of Wheeling, W.Va., and graduate of Washington University in St. Louis, Mo., was Charlotte’s first resident architect.3 He had come to this community in 1891 to teach mechanical drawing in the Charlotte Graded School, which was situated in the building at the northern edge of Dilworth that had formerly housed the North Carolina Military Institute.4 By 1892, Hook had entered private practice as an architect.5 By the end of his career, Hook had established himself as an architect of importance not only to Charlotte but also to the Piedmont sections of the two Carolinas. Locally, he fashioned such imposing edifices as the Charlotte Woman’s Club, the Charlotte City Hall, the James B. Duke Mansion and the Charlotte Masonic Temple, to mention only a few.6 He designed houses in Gastonia, Salisbury, Spartanburg and elsewhere.7 Most of his early commissions, however, were for houses in Dilworth, the streetcar suburb that the Charlotte Consolidated Construction Company or Four C’s had opened on May 20, 1891.8 Indicative of Hook’s identification in the public mind with the early residential architecture of Dilworth was an article which appeared in the Charlotte Observer on May 20, 1897. “An advertisement that always shows for Mr. Hook’s skill and taste is to be found in the houses in Dilworth, which he designed, and which show the best features of modern architecture,” the newspaper proclaimed.9 Hook was a specialist in the Colonial Revival style; but he did render houses in the Queen Anne style, an architectural motif which achieved its greatest popularity during the Victorian era.10 Only two Queen Anne style homes that one can definitively attribute to C. C. Hook survive in Dilworth. They are the Mallonee-Jones House (1895), which has already been designated as “historic property” upon the recommendation of the Historic Properties Commission, and the Robert J. Walker House (1901) at 329 E. Park Ave.

Robert Jefferson Walker (1870-1923) and his wife, Hattie Chariton Walker (1876-1967), moved into their new home in Dilworth in November 1901.11 Having grown up in Charleston, S.C., he was a regional representative for the Berlin Aniline Works, a German firm which produced dyestuffs. After the outbreak of World War I, Mr. Walker continued his association with the dyestuffs industry as a representative for the Atlantic Dyestuffs Company. At the time of his death on July 11, 1923, he was also president of the Charlotte Knitting Company.12 In the opinion of the Charlotte News, Robert J. Walker was “prominently connected in community affairs.” 13 He was a member and vestryman at Holy Comforter Episcopal Church in Dilworth; he served on the Board of Directors of St. Peters Hospital in Fourth Ward and on the Board of Directors of Thompson Orphanage. He was a Mason and a Shriner.14

Mattie Chariton Walker lived in the house for many years after her husband’s death. After an extended illness, she died in the Wesley Nursing Center in Charlotte on November 3, 1967. She was ninety-one years old. A native of Savannah, Ga., Mrs. Walker, in keeping with the values and customs of her upbringing, devoted most of her time and energy to rearing the six children (three boys and three girls) which she and Mr. Walker had brought into this world. She was also a charter member of Holy Comforter Episcopal Church and an active participant in the Daughters of the American Revolution. 15

On October 4, 1972, Kenneth D. Williams, Jr., and his wife, Helen C. Williams, bought the house from Mary Belle N. Lowry, who had owned the property since May 1944 and had resided there as well. Mr. and Mrs. Williams have been meticulously restoring the house. Happily, Mr. Williams is an architect. 16

Footnotes:

1 Charlotte Observer (June 9, 1901), p. 5.

2 Charlotte Observer (October 13, 1898), p. 5.

3 George Welch, a resident of Charlotte, did design several structures in the community in the 1870’s, including Second Presbyterian Church, the opera house and the jail. None of these structures is extant. Apparently, Welch was not a professional architect (Charlotte News (April 15, 1901), p. 1.).

4 Charlotte News (September 17, 1938), p. 12.

5 Charlotte Observer (April 3, 1892), p. 4.

6 Dan L. Morrill and Ruth Little Stokes, “Survey and Research Report on the Clubhouse of the Charlotte Woman’s Club.” (a manuscript produced for the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Properties Commission, April 1978). Dan L. Morrill and Jack O. Boyte, “Survey and Research Report on Lynnwood (James B. Duke House).” (a manuscript produced for the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Properties Commission, January 1977). Dan L. Morrill and Caroline I. Mesrobian, “Survey and Research Report on the Charlotte City Hall.” (a manuscript produced for the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Properties Commission, February 1980). Dan L. Morrill and Laura A. W. Phillips, “Survey and Research Report on the Masonic Temple.” (a manuscript produced for the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Properties Commission, April 1980).

7 For a representative sample of the work of Hook and Sawyer, see Some Designs By Hook & Sawyer, Architects, Charlotte, N.C., 1892-1902 (Queen City Printing & Paper Co., Charlotte, N.C.). A copy is available in the Carolina Room of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Public Library.

8 Charlotte News (May 20, 1891), p. 1. The president of the Charlotte Consolidated Construction Company was Edward Dilworth Latta.

9 Charlotte Observer (May 20, 1897), p. 3.

10 Charlotte Observer (September 19, 1894), p. 4. Charlotte Observer (June 4, 1893), p. 6.

11 Charlotte Observer (November 7, 1901), p. 5.

12 Charlotte Observer (July 12, 1923),p. 5.

13 Charlotte News (July 12, 1923), p. 6.

14 Charlotte Observer (July 12, 1923), p. 5.

15 Charlotte Observer (November 4, 1967), p. 4B.

16 Interview of Helen C. Williams by Dr. Dan L. Morrill (October 28, 1980). Mecklenburg County Deed Book 1125, Page 19. Mecklenburg County Deed Book 3482, Page 294. The original deed to the property is recorded in Mecklenburg County Deed Book 168, Page 220.

7. A brief architectural description of the property: This report contains an architectural description of the property prepared by Caroline I. Mesrobian, Architectural Historian.

8. Documentation of why and in what ways the property meets the criteria set forth in N.C.G.S. 160A-399.4:

a. Special significance in terms of its history, architecture and/or cultural importance: The Commission judges that the property known as the Robert J. Walker House does possess special historic significance in terms of Charlotte-Mecklenburg. The Commission bases its judgment on the following considerations: 1) it is one of only two known Queen Anne style houses in Charlotte which can be attributed to C. C. Hook, an architect of local and regional importance; 2) it is one of the few Victorian style houses which survive in Dilworth, Charlotte’s initial streetcar suburb.

b. Integrity of design, setting, workmanship, materials, feeling and/or association: The Commission judges that the architectural description included herein demonstrates that the property known as the Robert J. Walker House meets this criterion.

9. Ad Valorem Tax Appraisal: The Commission is aware that designation would allow the owner to apply annually for an automatic deferral of 50t of the Ad Valorem taxes on all or any portion of the property which becomes “historic property.” The current Ad Valorem appraisal on the Robert J. Walker House is $12,780. The current Ad Valorem appraisal on the .192 acres of land is $2,750. The most recent Ad Valorem tax bill for the house and land was $314.54. The land is zoned R6MF.

Bibliography

. Charlotte News

Charlotte Observer

Interview of Helen C. Williams by Dr. Dan L. Morrill (October 28, 1980) .

Dan L. Morrill and Jack O. Boyte, “Survey and Research Report on Lynnwood (James B. Duke House).” (a manuscript produced for the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Properties Commission, January 1977).

Dan L. Morrill and Ruth Little Stokes, “Survey and Research Report on the Clubhouse of the Charlotte Woman’s Club.” (a manuscript produced for the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Properties Commission, April 1978).

Dan L. Morrill and Caroline 1. Mesrobian, “Survey and Research Report on the Charlotte City Hall.” (a manuscript produced for the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Properties Commission, February 1980) .

Dan L. Morrill and Laura A. W. Phillips “Survey and Research Report on the Masonic Temple.” (a manuscript produced for the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Properties Commission, April 1980) .

Records of the Mecklenburg County Register of Deeds Office.

Records of the Mecklenburg County Tax Office.

Some Designs By Hook & Sawyer, Architects, Charlotte, N.C., 1892-1902 (Queen City Printing & Paper Co., Charlotte, N.C.).

Vital Statistics of Mecklenburg County.

Date of Preparation of this Report: November 5, 1980

Prepared by: Dr. Dan L. Morrill, Director

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Properties Commission

3500 Shamrock Dr.

Charlotte, N.C. 28215

Telephone: (704) 332-2726

Architectural Description

This Queen Anne style house, located on the northwest quadrant of the intersection of Euclid and E. Park Avenues in Dilworth, was designed by Charles C. Hook for Robert J. Walker in 1901. The two story frame house, with basement and high attic, is a fine example of Victorian eclecticism, with a variety of wall surfaces, porches, roof lines, and window types.

The front elevation (southwest) features a wood shingled porch which shelters the central entrance and a double hung, 1/1 window. This section of the facade, which projects from the main block of the house, is accentuated by a gambrel roof, it featuring a large Palladian window. The remainder of the facade, which is weatherboarded, contains a first story picture window with stained glass transom and a second story double hung, 1/1 window. A tiny oriel window punctuates the steeply pitched gable roof. A one story porch with classical columns spans the intersection of this facade and the right side elevation (southeast) a bay window faces the intersection of E. Park and Euclid Avenues on both stories.

An exterior chimney with central, arched recess dominates the right side elevation. Fenestration includes a picture window with stained glass transom and double hung, 1/1 windows of varying sizes in the second story as well as in the recessed section on the first floor. Oval end windows pierce the double gable roof. A single bay, rear wing features a double hung, 2/2 window. The side of this wing which faces the rear elevation (northeast) contains two centrally placed double hung, 2/2 windows, the upper one within the gambrel roof end. The main block contains an end, double hung, 2/2 window on both stories.

The left side elevation (northwest), which once overlooked the Walker’s side yard and garden, is perhaps the most varied of all the house’s elevations. It is comprised of the main block flanked by a rear wing with side entrance reached by a single flight of stairs, and a front wing featuring the side of the porch which faces onto E. Park Ave. Above this is a small oriel window. The main block is punctuated by double hung, 2/2 windows flanking a central, projecting bays it contains an attenuated double hung window which lights the interior stairwell. An interior chimney projects from the gable roof end.

On the interior, the first floor (ceiling height 11 feet) contains four major rooms which flow into one another in a circular fashion through double sliding doors. The entrance hall (southwest) features a massive staircase which rises two flights to the second floor. A fireplace, comprised of a classical mantel with columns and bead and reel decoration and a marbleized tile surround and hearth is located beneath the stairway. The floor, as in the other public rooms, hasa parquet border; this particular one is formed by narrow oak boards stained in several different shades for contrasting effect.

The parlor (southeast) is the most elegant room in the house. Plaster relief panels in the form of intertwined leaves divide the wall areas; the walls themselves still show remnants of a jade green satin damask fabric bearing an iris pattern. The corner mantel and mirrored overmantel adorned with classical columns are of bird’s-eye maple and have never been painted. The parquet floor appears to be composed of oak, maple, and mahogany, and is laid in an interlocking fret pattern. The ceiling fixture is of solid brass and is original to the house.

The east back room, the dining room, features a corner mantel with brackets and attenuated columns. Its surround and hearth are composed of marbleized green tiles moulded in the shape of shells. Bands of variously shaded, stained wood form the border of the floor. A butler’s pantry and kitchen are behind the dining room, while the room directly behind the entrance hall (northwest) was used originally as a den.

The second floor (ceiling height 10 feet) contains five major rooms; three of them were used by the Walker family as bedrooms and a nursery. The small room above the den was used as an office by Mr. Walker, while the back room directly above the kitchen wing was the servant’s quarters.

The 1911 Sanborn Insurance Map shows that a stable and automobile garage were located at the rear of the property. Neither exist today; the stable was demolished before the 1929 Sanborn Insurance inventory was taken.