The Welch-McIntosh House

This report was written on June 9, 1997

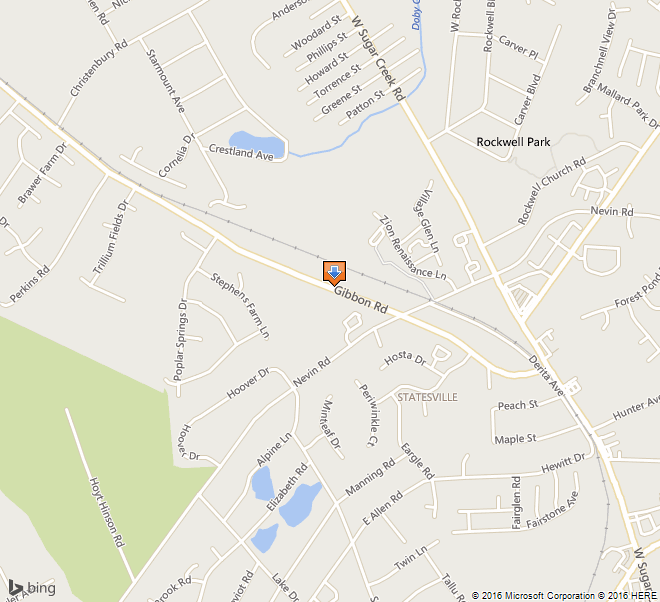

1. Name and location of the property: The property known as the Welch-McIntosh House is located at 3301 Gibbon Road in the Derita community of Charlotte in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina.

2. Name, address, and telephone number of the present owner of the property: The owner is :

Charlotte – Mecklenburg Historic Preservation Foundation, Inc.

2100 Randolph Road

Charlotte, North Carolina 28207

(704) 375-6145

3. Representative Photographs of the property: This report contains interior and exterior photographs of the property.

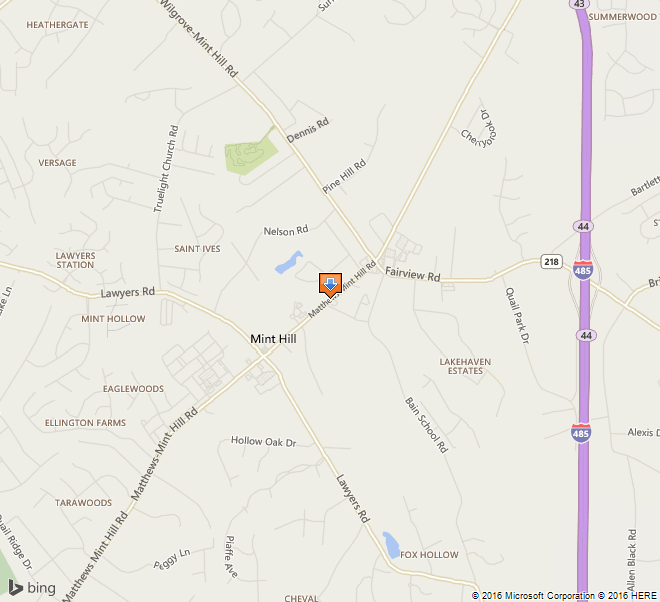

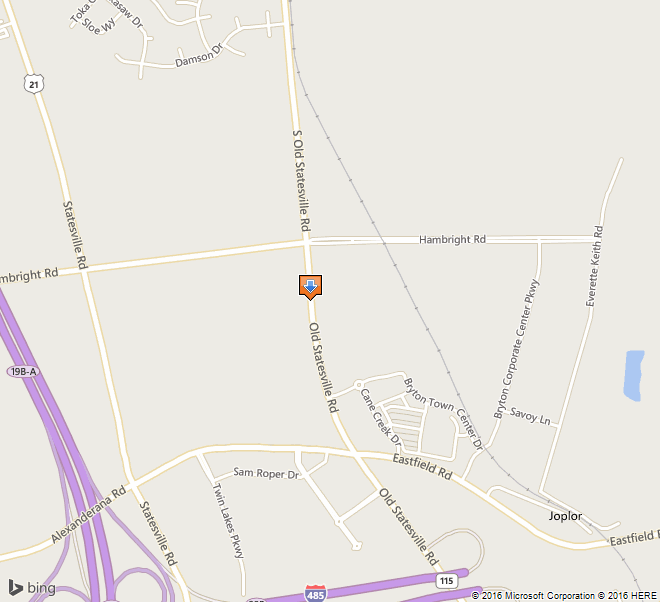

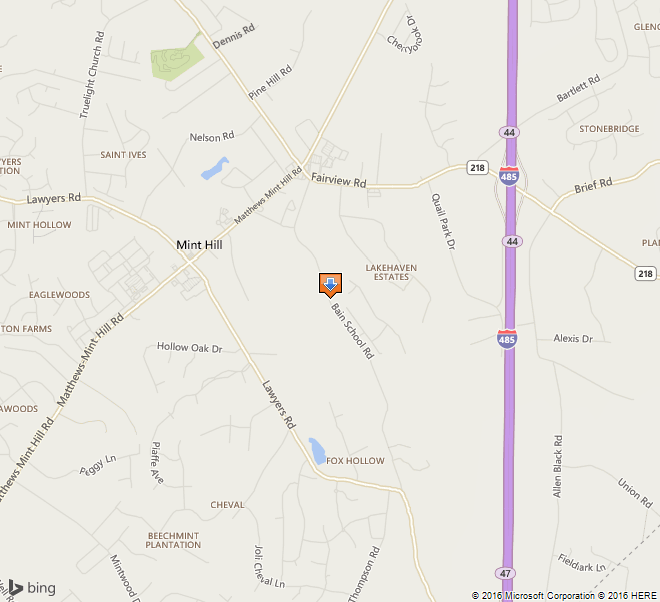

4. Maps depicting the location of the property: This report contains a map depicting the location of the property.

5. Current deed book references to the property: The most recent deed to the Welch-McIntosh House is listed Mecklenburg County Deed Book 8834 at Page 364. The Tax Parcel Number of the property is 045-372-27.

6. A brief historical description of the property: This report contains a historical sketch of the property prepared by Dr. Dan L. Morrill.

7. A brief architectural description of the property: This report contains an architectural description of the property prepared by Dr. Dan L. Morrill.

8. Documentation of why and in what ways the property meets criteria for designation set forth in N.C.G.S. 160A-400.5:

a. Special significance in terms of history, architecture, and cultural importance: The Commission judges that the property known as the Welch-McIntosh House does possess special significance in terms of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County. The Commission bases its judgment on the following considerations: 1) the Welch-McIntosh House is the best preserved example of a transition Queen Anne style cottage in the Derita community, 2) the Welch-McIntosh House documents the dispersal of urban architecture into sections of rural Mecklenburg County in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and 3) George Stewart Welch (1867-1935) and Clara Rumple Welch (1868-1953), the initial owners of the house, demonstrate the impact of Charlotte upon the development of truck farming in turn-of-the-century Mecklenburg County.

b. Integrity of design, setting, workmanship, materials, feeling, and association: The Commission contends that the architectural description by Dr. Dan L. Morrill included in this report demonstrates that the Welch-McIntosh House meets this criterion.

9. Ad Valorem Tax Appraisal: The current Ad Valorem appraised value of the 1.501 acres of land is $49,010. The current Ad Valorem appraised value of the house is $4,290. The total Ad Valorem appraised value is $53,300. The property is zoned R12MF.

Date of Preparation of this Report: June 9, 1997

Prepared by: Dr. Dan L. Morrill

Historic Landmarks Commission

2100 Randolph Road

Charlotte, N.C. 28207

Physical Description

Dr. Dan L. Morrill

June 9, 1997

Location Description

The Welch-McIntosh House is located on Gibbon Road in the Derita community in the north central portion of Mecklenburg County. Derita is approximately six miles north of the city center of Charlotte. Sited on 1.501 acres of land on the south side of Gibbon Road, the Welch-McIntosh property is located approximately one-half mile west of Derita’s commercial district, which borders the tracks of the Atlantic, Tennessee & Ohio Railroad, now Norfolk Southern Railroad, which extend from Charlotte to just beyond Mooresville, N.C. The Welch-McIntosh House is sited on a slight knoll, and a lawn and a semicircular, gravel driveway separate the house from Gibbon Road. The lawn contains mature trees. To the rear of the house, the site descends gradually toward a creek. The only other structures on the site are a well house to the immediate rear of the house, a privy and a small storage shed. The proposed designation includes the Welch-McIntosh House (interior and exterior) and 1.501 acres of land, plus the privy and the well house.

Architectural Description

The Welch-McIntosh House is a one and one-half story, double pile, frame building with a one story rear ell on the southwest side of the house. The house has weatherboard siding; a brick pier foundation (infilled except for the porches during restoration), and a hip roof covered in slate. A wide, balustraded wraparound porch is on the front of the house, and an “L-shaped,” balustraded porch extends across the back of the house and along the east side of the rear ell. The front wraparound porch has a shed, composition roof. A rock rubble stairway leads to the front porch, which is surmounted at the front entrance by a pedimented gable with broad eaves with returns. The main body of the roof also has broad, overhanging eaves, as does a pedimented gable which is located on the northwest corner of the house. The front door with transom is original. Surrounded by a symmetrically molded architrave with corner blocks, it retains its original screen door, which is modestly decorated with filigree. Original doorways also open on to the rear porch, one directly opposite from the front entrance and two along the rear projection of the “L-shaped” porch (the door closer to the rear now opens on to an enclosed laundry room). Two interior brick chimneys, each with a modestly corbeled cap, penetrate the roof of the main block of the house; and an interior brick chimney with plain cap extends above the roof of the rear el. The predominant window type is 2/2 sash with large lights or panes. Pedimented dormers of identical design with replacement windows are located on the center portions of the front and rear elevations of the house. The interior of the Welch-McIntosh House is strikingly original. The only major changes have been the construction of a bathroom in the 1950’s near the rear of a wide center hall that extends from the front to the back of main block of the house, and the placement of updated cabinets and fixtures (also in the 1950’s) in the kitchen at the southern end of the rear ell. Otherwise the interior features date from 1907. These include the mantels in the front four rooms, the doorways and their hardware and surrounds, the base and ceiling molding, the wainscoting in the center hall, and the newels, handrail, and pickets of the “L-shaped” stairway that leads from the center hall in a single landing to the second floor, which contains two rooms, completely paneled.

Conclusion

The Welch-McIntosh House has been modified. A modern bathroom was installed in the 1950’s, and the kitchen was updated in the same decade. At some point in time the rear porch was extended over the well house — a feature which was eliminated during the recent restoration of the house — and portions of the front porch were demolished — the missing portions of the front porch were rebuilt earlier this year. The spring house no longer exists, nor do most of the outbuildings used during the years when George Welch occupied the property as a farmer. The brick pier foundation has been infilled with block which has been recessed. New cabinets have been placed in the kitchen, and the house has a new central air conditioning and heating system. On balance, however, the Welch-McIntosh House, both inside and outside, is largely original. The house has individual significance architecturally because it is the best preserved example of its stylistic genre in the Derita community. Also, it demonstrates how an essentially urban style, the transitional Queen Anne style cottage, spread into rural Mecklenburg County in the early twentieth century, especially into areas which were closely linked to Charlotte by the railroad.

A History of the Welch-McIntosh House

Dr. Dan L.Morrill

June 9, 1997

The Welch-McIntosh House was built in 1907 as the home of George Stewart Welch (1867-1935) and his wife, Clara Lee Rumple Welch (1868-1953), whom he had married on April 9, 1894. She was a native of Mecklenburg County and Derita.1 This was not the couple’s first home in the Derita community. Previously renters, they decided to construct a residence on farm land that Mr. Welch had already purchased.2 It is also reasonable to assume that Welch and his wife needed a larger abode to rear their seven children — three sons and four daughters.3 The oldest child was only 10 years old when the Welches moved into the Gibbon Road house.

A large, convivial man who enjoyed joking with and teasing his children, George Welch was a resourceful and imaginative truck farmer. In addition to raising crops, he was a dairyman and tended peach, apple and pear orchards. He regularly delivered milk, butter, fruits and vegetables to customers in Charlotte. One of Welch’s stops was the Berryhill Store in Fourth Ward, where he would deposit his farm products and pick up supplies for his wife.4 Another of his enterprises was establishing and superintending the North Derita Poplar Springs, which was situated at the bottom of the hill behind the house. “I wish to announce that I have opened the above Springs near Derita and am prepared to properly fill orders in any quantity at reasonable prices,” Welch declared in an advertising circular that appeared in 1911. The circular contains a photograph of a gable-roofed spring house (no longer extant) and a horse-pulled delivery wagon. The product, of course, was pure drinking water.5 Later the spring house was used to refrigerate milk produced by Welch’s cows.6 George Welch took an interest in community affairs, especially education. He was the School Committee Chairman of the Derita School for many years.7 The Derita community grew up along the tracks of the Atlantic Tennessee & Ohio Railroad in the second half of the nineteenth century.8 Now almost totally engulfed by Charlotte’s suburban sprawl, Derita was once a distinct trading center for farmers in the region. The centerpiece of the neighborhood was the commercial district beside the railroad tracks about one-half mile east of the Welch-McIntosh House.

A leading storekeeper and the first postmaster in the community was Amos L. Rumple, Clara Welch’s father. He gave Derita its name. He named it after one of his best friends, Derita Lewis.9 The Welch-McIntosh House is situated on Gibbon Road, which parallels the tracks of the railroad just northwest of Derita. Consequently, even in 1907, it stood on a well-traveled road and was, therefore, readily accessible from the outside world. The house is a more or less standardized early twentieth century dwelling, suggestive more of urban or small town building forms than those found in the countryside. It is of balloon-framed construction with mass-produced sawn lumber and nails.10 Stylistically, the Welch-McIntosh House is a Queen Anne style cottage. Part of the picturesque movement, the Queen Anne style had been gaining popularity in Mecklenburg County since the 1870’s. “Contrasting sharply with simple square or rectangular folk house types, Queen Anne dwellings displayed consciously irregular forms, with jutting wings and bays topped by interlocking hip and gable roofs,” writes architectural historian Richard L. Mattson.11 George Welch, a diabetic in his later years, died in the Welch-McIntosh House on November 7, 1935, and was buried in the Sugar Creek Cemetery immediately across Sugar Creek Road from the Church.12 His daughter, Ona Welch Puckett, described her father thusly:

George Welch was a large man, usually weighing about 185-200 pounds. He was grey at a very early age. He had a mustache part of his life, but shaved it off in his late years of life. . . . He had blue eyes and fair skin.13

Clara Welch lived until June 3, 1953, when she too died in the house.14 Clara, a life-long member of Sugar Creek Presbyterian Church, is buried beside her husband. According to her daughter Ruby McIntosh, Clara was a “quiet, gentle person” who spent most of her years performing the routine chores of homemaking — cooking, washing, cleaning, etc. She enjoyed the services of an African American maid, named Edna, for many years.15 Canning of vegetables from the garden lasted throughout the summer. Animals, including pigs and horses, had to be fed. A typical meal for the family would consist of corn, squash, beans, pork and cornbread. Clara never complained and, according to her daughter, never had an argument with her husband.16 According to Maurice McIntosh, Clara adamantly refused to have a bathroom put in the house. She simply did not think it appropriate to use indoor facilities. Consequently, the family continued to use the outhouse, which still stands behind the dwelling, until after Clara’s death in 1953.17

In 1936, Ruby Welch (1908 – ) married Fred Campbell McIntosh (1899-1953), a native of Sanford, N.C. The two had met several years earlier on the front porch of the Welch-McIntosh House, when he had accompanied a friend from Charlotte on a visit. The next year Ruby and her husband established residency in the house on Gibbon Road, because Ruby’s sister, Ona, had moved into Derita, leaving Clara alone. Fred McIntosh resided in the house until his death in 1953, and Ruby stayed on until 1995, when she moved to a son’s house on Shasta Lane in Charlotte. Fred and Ruby McIntosh had two children, both sons. They are Alfred Welch McIntosh (1939- ) and Maurice Daniel McIntosh (1940- ).18

Fred McIntosh was a marble and tile setter. An employee of Renfrow Tile and Marble Co. in Charlotte, he would lay tile in bathrooms of new homes, install broken-tiled porches at houses, and place marble and tile floors in commercial and industrial buildings, including the River Bend Duke Power Plant in Gaston County. An outdoorsman, he loved to go fishing with his two sons and tell them what to do. “Don’t go to close to the shore.” “Row over that way.” Ruby McIntosh, a nurse, worked outside the home after her children started to school in the mid-1940’s. She continued to rear her children after her husband’s death and met her many responsibilities with a quiet but resolute demeanor. Maurice McIntosh remembers his childhood in the Welch-Mcintosh House as an almost ideal, rural existence. He and his brother Alfred used to catch all sorts of animals, pin them up, and nurture them. These included frogs, birds of all sorts, squirrels, and snakes. Maurice was also fond of guns. He would “ping bees” from the beehive that was always at the corner of the house with his BB gun and shoot rats with his 22 rifle when they ran across the fields of neighboring farmers at hay harvesting time.19 In 1995, the Welch-McIntosh House became rental property. The following year the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Preservation Foundation acquired the house through donation from Ruby McIntosh and began restoring it. That effort is still underway at the time of the preparation of this report.

1 “Welch Family History,” compiled by Ona Welch Puckett (April, 1972). A copy of this manuscript is in the files of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission. Mecklenburg County Marriage Book 47, p. 646.

2 Interview of Ruby Welch McIntosh and Maurice Daniel McIntosh by Dr. Dan L. Morrill (May 28, 1997). Hereinafter cited as “Interview.”

3 The children of George and Clara Welch were Earl Parks Welch (1895-1984), Oscar Blaine Welch (1897-1984), Waldo Pharr Welch (1901-1953), Ona Marie Welch Puckett (1904-1996), Mabel Bertina Welch Ellis (1906-1994), Ruby Hazeline Welch McIntosh (1908- ), and Beulah May Welch Dean (1912- ). See “Welch Family History.”

4 Interview.

5 “Welch Family History.” An original copy of this advertising circular is in the files of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission. A concrete pad still marks the spot of the spring house at the edge of the creek behind or south of the house.

6 Interview. Maurice McIntosh says that there used to be a “churn house” immediately behind the main house, where milk was turned into butter. He also remembers a row of milking stalls behind the house.

7 “Welch Family History.”

8 The Atlantic, Tennessee and Ohio Railroad opened in 1860. The tracks were taken up during the Civil War, because the Confederacy was in desperate need of track for its heavily traveled railroads. The line did not reopen until 1874 as part of the Atlanta & Charlotte Air Line. Its auspicious name notwithstanding, the Atlantic, Tennessee and Ohio only ran from Charlotte to Statesville, N.C. See Thomas W. Hanchett, “Charlotte And Its Neighborhoods. The Growth of a New South City, 1850-1930” (1986), p. 16, an unpublished manuscript in the files of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission.

9 Christina Wright and Dr. Dan Morrill, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Tours. Driving and Walking (Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Preservation Fund, Inc., 1994), p. 30.

10 According to Ruby Welch McIntosh, the house was built by a “Mr. High.” Also, the lumber was fashioned from trees cut from her uncle’s farm on Beatties Ford Road (Interview).

11 Richard L. Mattson, “Historic Landscapes Of Mecklenburg County,”(1991), pp. 20-21, a manuscript in the files of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission.

12 Mecklenburg County Death Book 47, Page 646. Charlotte Observer (November 8, 1935).

13 “Welch Family History.”

14 Charlotte Observer (June 4, 1953).

15 Interview.

16 Interview.

17 Telephone conversation with Maurice McIntosh by Dr. Dan L. Morrill (May 29, 1997).

18 Interview.

19 Interview.