THE GEORGE PIERCE WADSWORTH HOUSE

This report was written on 20 March 1994

1. Name and location of the property: The property known as the George Pierce Wadsworth House is located at 400 S. Summit Avenue in the Wesley Heights neighborhood of Charlotte, Mecklenburg County, North Carolina.

2. Name address and telephone number of the present owner of the property: The owner of the property is:

Mr. Charles McClure

McClure Properties, Inc.

3027 Maple Grove Drive

Charlotte, North Carolina 28208

(704) 332-1559

3. Representative photographs of the property: This report contains representative photographs of the property.

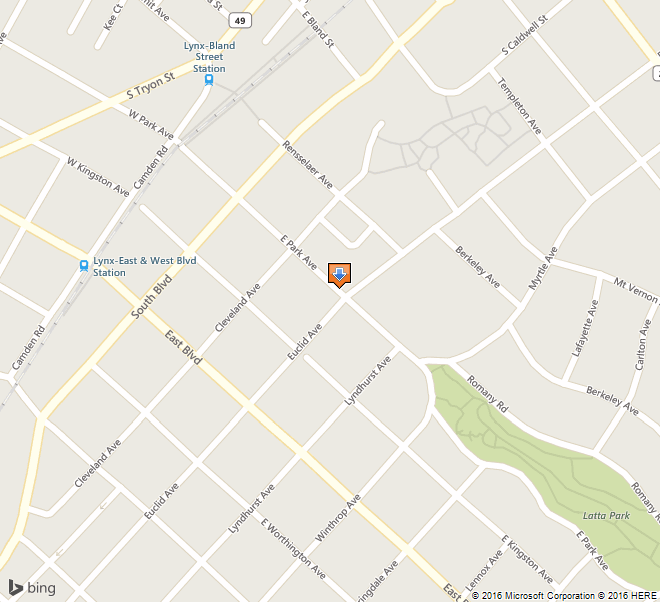

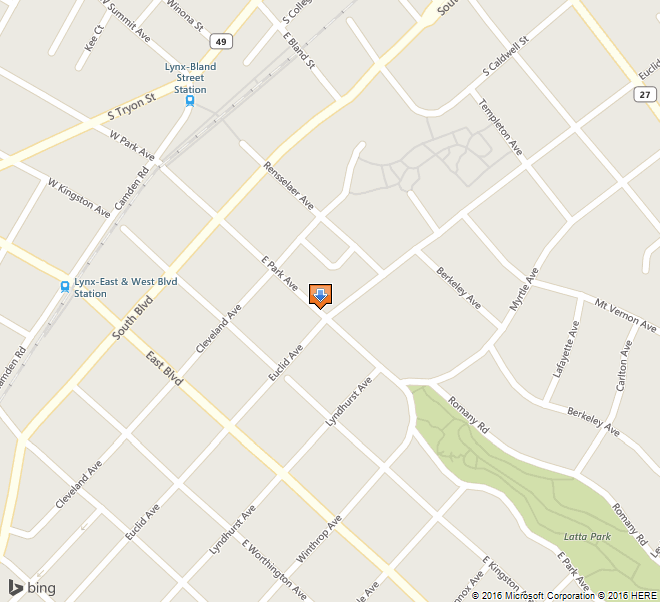

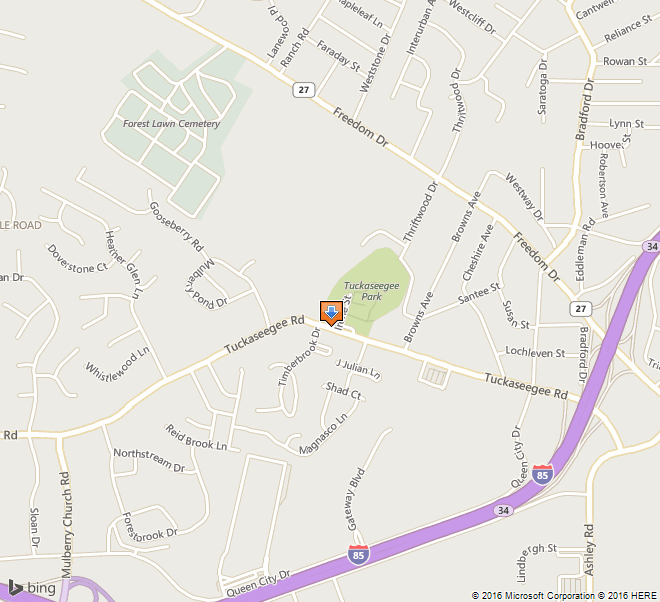

4. Maps depicting the location of the property: This report contains maps which depict the location of the property.

5. Current deed book references to the property: The George Pierce Wadsworth House is sited on Tax Parcel Number 071-24-11 and listed in Mecklenburg County Deed Book 3914 at page 503.

6. A brief historical sketch of the property: This report contains a brief historical sketch of the property prepared by Frances P. Alexander.

7. A brief architectural description of the property: This report contains brief architectural description of the property prepared by Frances P. Alexander.

8. Documentation of why and in what ways the properties meet criteria for designation set forth in N.C.G.S. 160A-400.5:

a. Special significance in terms of history, architecture, and cultural importance: The Commission judges that the property known as the George Pierce Wadsworth House property does possess special significance in terms of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County. The Commission bases its judgement on the following considerations:

1) the George Pierce Wadsworth House was designed in 1910 by prominent North Carolina architect, Louis H. Asbury;

2) the George Pierce Wadsworth House is one of the earliest houses in the westside streetcar suburb of Wesley Heights;

3) the George Pierce Wadsworth House was the home of an important local businessman, whose enterprises illustrate the economic activities of the city during the early twentieth city;

4) the George Pierce Wadsworth House, and subsequent residential construction in Wesley Heights, illustrate the expansion of the city through the suburban subdivision of surrounding farmsteads; and

5) the George Pierce Wadsworth House property contains a servant’s quarters/carriage house, an increasingly rare building type in the city of Charlotte.

b. Integrity of design, setting, workmanship, materials, feeling, and association: The Commission contends that the architectural description by Frances P. Alexander included in this report demonstrates that the George Pierce Wadsworth House property meet this criterion.

9. Ad Valorem Tax Appraisal: The Commission is aware that designation would allow the owner to apply for an automatic deferral of 50% of the Ad Valorem taxes on all or any portion of the property which becomes a designated historic landmark. The current appraised value of the improvements to the George Pierce Wadsworth House is $153,210.00. The current appraised value of the George Pierce Wadsworth House, Tax Parcel Number 071-024-11 is $54,700.00. The total appraised value of the George Pierce Wadsworth House is $207,910.00. Tax Parcel Number 071-024-11 is zoned 02.

Date of Preparation of this Report: 20 March 1994

Prepared by: Frances P. Alexander, M.A.

for

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission

P.O. Box 35434

Charlotte, North Carolina 28235

(704) 376-9115

Physical Description

Location and Site Description

The George Pierce Wadsworth House is located in the Wesley Heights neighborhood, an early twentieth century streetcar suburb, of Charlotte, North Carolina. The Wadsworth House sits on a corner lot at the junction of South Summit Avenue and West Second Street, two blocks north of the West Morehead Street thoroughfare. The tracks of the former Piedmont and Northern Railway follow Litaker Street, one block south of the Wadsworth House. This house is one of the larger and earlier houses in this residential neighborhood of tree-lined streets. Much of the surrounding neighborhood dates to the 1920s and 1930s.

Facing Summit Avenue, the George Pierce Wadsworth House is sited off-center on its lot with a curved drive and porte cochere on the West Second Street side and a circular drive between the rear of the house and the servant’s quarters. Portions of the original scored carriage driveway with high rounded curbs remain. The servant’s quarters/carriage house is located directly to the rear of the main house. An original walkway runs along the front of the house with a walkway and steps connecting the front walk with the rear drive. The gardens and yard are found on the south and southwest sides of the house. Vestiges of the terraced lawn survive as do some original plantings, including now mature oak and maple trees. The Wadsworth House is now operated as a funeral home.

The proposed designation includes the house, the servant’s quarters/carriage house, and the surrounding yard.

Architectural Description

Main House

The George Pierce Wadsworth House is a large, two and one-half story, frame house sheathed in wood shingles. The house has a truncated L-shaped plan formed by the rectangular massing of the main block and the two story rear ell. The house has a raised, brick foundation, a hip roof covered in asphalt shingles, overhanging eaves, and hip roofed dormers. A hip roofed porch extends across the facade and terminates in a porte cochere on the north side. The wide porch has shingled box piers and a shingled skirt between the piers. The facade has four irregularly placed bays and an off-center entrance. The wide entrance has divided sidelights and transom, and the door has a multiple light upper section. The windows vary in size and type, but most are sixteenover-one light, double hung, wooden sash. Banks of Craftsman style windows are located in the southwest corner of the second floor, corresponding to a sleeping porch. An inset summer porch beneath the sleeping porch has a hipped roof bay on the southwest elevation and a single entrance, with transom, on the rear elevation. The window openings in the bay and rear door are screened. The house has both interior and exterior brick chimneys. A molded projecting cornice divides the two main floors of the house.

The rear ell has an irregular massing. The first floor has a gable roof with an engaged porch roof over an enclosed porch. A modern double loading door and a single door are found on the rear elevation of the enclosed porch. The second floor is smaller than the first and has a hip roof extending from the roof of the main block.

The interior has a wide, formal entrance hall which extends to the rear porch. A horizontal paneled door separates the rear porch from the entrance hall. The front hall is flanked by a long living room and a dining room. The entrance hall now has linoleum floors, but the plaster walls, wide, molded door surrounds, base moldings, and a tall chair railing are original. A broad staircase, with square, classical box balusters and curved newel, rises to a landing with a segmental arched, stained glass window. The window has a fixed light transom, and the lower section is a casement window. The stairs are now carpeted. At the stair landing, there is a door opening which originally contained a staircase to the attic. This opening is now closed.

The long living room is separated from the hall by paneled pocket doors. Opposite the hall doorway is a fireplace with a paneled mantel. The ceiling has exposed wooden beams, with original drop globe lamps, and the hardwood floors of the living room are now carpeted. Double multiple light doors in the southwest corner of the room open into the summer porch.

The dining room also has plaster walls and exposed ceiling beams, paneled wainscoting, and Arts and Crafts chandelier, but no fireplace. A paneled door in the northwest corner opens into a butler’s pantry which, in turn, leads into the kitchen. The hardwood floors in the dining room are carpeted. The butler’s pantry has built-in cabinets along the interior walls.

Behind the living room is a small study. The study opens off a small hall, with a closet and small bathroom. Opposite the hall door to the study is a multiple light door, opening onto the summer porch. The doors and windows repeat the broad, molded surrounds, and there is a wide, flat chair railing. The study has a notable oversized fireplace mantel constructed of brick. The mantel is composed of a flat, brick back wall from which a molded classical mantel projects. The room also contains original Arts and Craft wall light fixtures. The hardwood floors in the study are also carpeted.

Located in the rear ell, the kitchen has undergone little alteration although it is now used as a preparation room for the funeral home. The kitchen repeats the wide, molded door and windows surrounds, and the use of horizontally paneled doors. Some original fixtures are intact. To the rear of the kitchen is the laundry room. Along the south side of the kitchen and laundry room is the enclosed porch which contains an open rear staircase leading to the second floor main staircase landing. The staircase has box balusters and newel. The walls and ceiling of the porch have the original vertical wood paneling except along the south wall where the porch has been enclosed. One window, along the kitchen wall, has been infilled. The second floor has four bedrooms, two sleeping porches, and two bathrooms. The second floor hall runs the width of the house, although a portion of the hall on the south side has a door opening to close off two bedrooms and a bathroom. The hall has original light fixtures. The bedrooms all have original horizontal paneled doors, wide, molded surrounds, and plaster walls and ceilings. The hall and the bedrooms are all now carpeted. Two of the bedrooms have fireplaces, and the paneled mantels are original. The bathrooms have their original fixtures, including freestanding tubs, sinks, and tile. The sleeping porch on the south side was used as a kitchen when this portion of the second floor was converted to an apartment, probably in the late 1940s. However, the kitchen fixtures are freestanding and have required little alteration.

The house has undergone relatively little alteration despite the change in function. Some general deterioration is evident, notably in the rear service areas of the house, but otherwise the historic fabric is intact.

Servant’s Quarters/Carriage House

The Servant’s Quarters/Carriage House is located at the rear of the property and is separated from the main house by the circular driveway. This building is a one story tall, frame building with a rectangular plan. This building has a brick foundation, shingled veneer, and asphalt shingled, hip roof. The two bays of the garage occupy the northern half of the building, and the living quarters the southern portion. The hinged, double doors to the garage appear to be replacements. The living portion of the building has an engaged porch at the south end, and the porch is supported by classical box piers. This south elevation has three irregular bays. The door occupies the easternmost bay, and there are two windows. The east elevation is symmetrical with a central entrance, covered by a modern metal awning, and two flanking windows. The windows in this building, as in the main house, are sixteen-over-one light, double hung, wooden sash. The building has one interior, brick chimney. The garage is still used as such, and the servant’s quarters are used for storage. The building has good integrity.

Historical Overview

The George Pierce Wadsworth House was designed by prominent North Carolina architect, Louis H. Asbury, in 1910, and construction was completed in 1911 (Louis H. Asbury, Book of Commissions, Job No. 71, July 1910). Local businessman, George Wadsworth commissioned Asbury to build his new house on property which the Wadsworth Land Company had recently subdivided into Wesley Heights, a middle class suburb located west of downtown between West Trade Street and W. Morehead Street. The George Pierce Wadsworth House was one of the first houses built in the new suburb which was called Wesley Park on early plans (C.G. Hubbel, Wesley Park Map, July 1910).

By 1892, much of the hillside between Tuckaseegee Road and Sugaw Creek had been acquired by George Wadsworth’s father, John W. Wadsworth (1835-1895), who ran the largest livery stable in Charlotte. In addition to his livery at North Tryon Street and Sixth Street, Wadsworth also assisted in operating the first horsedrawn streetcar system in the city. Coming to Charlotte in 1857, John Wadsworth began with a small drove of mules and gradually built a large livestock, carriage, and harness business while acquiring extensive land holdings in the city and county (Hanchett, 1984: 14; Mull, 1985: 1). On the westside parcel, where the George Pierce Wadsworth House was later built, Wadsworth operated the “J.W. Wadsworth Model Farm”, which was known for its Holstein cattle. At his death in 1895, Wadsworth’s heirs incorporated the livery and livestock business as Wadsworth Sons Company and subdivided the farm. However, development was delayed after 1909, when the West Trade Street trolley began service north of the property. With streetcar service, the Wadsworths began plans for developing the former farm, but construction was again largely stalled until after World War I when the Charlotte Investment Company bought the land.

George Wadsworth was born in 1879 to John Wadsworth and Margaret Cannon Wadsworth, sister of J.W. Cannon, founder of Cannon Mills. After college in Virginia and Baltimore, George Wadsworth returned to Charlotte to assume the presidency of Wadsworth Sons Company in 1902. George Wadsworth soon began diversifying the family business interests, a necessary step as automobile travel began replacing horsedrawn conveyances. In 1912, he organized Smith-Wadsworth Hardware Company, and in 1914, he helped establish the Carolina Baking Company, which later was subsumed within the Southern Baking Company. Wadsworth was also associated with the Charlotte National Bank as a director. In 1925, Wadsworth Sons Company was liquidated, ending seventy years of local livery and livestock operations. Wadsworth continued his business interests with the Wadsworth Land Company and the Wadsworth-Seborn Company, a sales operation for Reo cars throughout the Carolinas. His other real estate operations included serving as an officer for the Pegram Land Company. The holdings of both Wadsworth and the Pegram Company were platted as North Charlotte (Mull, 1985: 2).

George Wadsworth commissioned Charlotte architect, Louis H. Asbury to design the house at 400 South Summit in 1910, two years after his marriage and the birth of two children. A Charlotte native, Asbury (1877-1975), had established his practice in the city only two years before the Wadsworth commission. Prior to returning to his hometown, Asbury had received his professional training at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and had worked for the nationally known firm of Cram, Goodhue, and Ferguson, in either its New York or Boston office. Later joined by his son, Asbury had an extensive regional practice until his retirement in 1956. A founding member of the North Carolina Chapter of the American Institute of Architects, Asbury was among a group of early architects in the city who brought a degree of sophistication, urbanity, and professionalism to early twentieth century building in Charlotte. His clients, exemplified by George Wadsworth, tended to be the businessmen responsible for the growing importance of Charlotte as a regional center for the textile and banking industries (Farnsworth, 1975: 16).

The Wadsworth family continued to live in the house after the sudden death of George Wadsworth in 1930 at the age of 51. James Dallas Ramsey, an officer of the Textron-Southern Company, and his wife, Pearl Shelby Ramsey bought the house in 1936. The Ramseys converted a portion of the west side of the second floor to an apartment and adapted a small sleeping porch as a kitchen, probably during the late 1940s. The Ramseys moved in 1967, and the house stood vacant for two years. In 1969, Mrs. Ramsey sold the property to prominent businessman, Worthy D. Hairston (1902-1969) and his wife, Marie S. Hairston. Hairston, a funeral director who had established the Hairston’s House of Funerals in 1930, moved his business from its Beatties Ford Road location to the Wadsworth House in 1969 (McClure Interview, 29 November 1993).

A Biddleville resident and the son of a Presbyterian minister, Worthy D. Hairston, had attended Charlotte public schools, Harbison College, and Johnson C. Smith University. Prior to forming the funeral home, Hairston was a builder, having trained as a carpenter, and a teacher in Mecklenburg and Gaston counties. His local building projects included the Murkland School in Providence Township, the first school for blacks constructed of stone, and the Grand Theater. Mr. Hairston also served as the first agent for the Washington National Insurance Company in Charlotte. In 1930, Hairston and a partner formed Hairston’s House of Funerals, but after his partner’s death in 1933, Hairston became the sole owner. Worthy Hairston lived less than a year after moving the funeral home to the Wadsworth House, and the Hairstons’ daughter, Marie H. Pettice, operated the business until her death in the mid-1970s. In 1977, Mrs. Hairston’s nephew, Charles McClure, bought the Wadsworth House property. McClure, vho already had an extensive real estate business as well as other commercial operations, continued to operate Hairston’s House of Funerals. McClure changed the name to Northwest Funerals Homes, Inc., and the business is still in operation at this site today (Mull, 1985: 4-5).

Unlike the other early streetcar suburbs in Charlotte, such as Myers Park, Dilworth, and Elizabeth, Wesley Heights was platted without the wide boulevards along which the streetcars ran and which were developed with large, impressive residences. Streetcar service, which was essential to the development of outlying locations prior to the widespread use of automobiles, was available nearby, but did not run through the Wesley Heights neighborhood. After World War I, the Charlotte Investment Company platted roughly half the land, including Summit Avenue, Grandin Road, and Walnut Avenue. The plat extended from West Trade Street and Tuckaseegee Road southwest of the interurban line of the Piedmont and Northern Railway which bisected the former farm parcel (Hanchett 1984: 15). (The Wadsworth House is located one block northeast of the railroad tracks.)

Wesley Heights was the work of Charlotte real estate developer, E.C. Griffith. Griffith, a Virginia native, was pivotal in the construction of many early twentieth century neighborhoods in Charlotte, and Wesley Heights was his first solo project in the city. Griffith had come to Charlotte to work in the real estate department of the American Trust Company, founded, with F.C. Abbott and Word Wood, by George Stephens. Stephens, who was responsible for subdividing the farm of his father-in-law, J.S. Myers, as Myers Park, employed Griffith to oversee the final construction of this streetcar suburb (Blythe, 1961: 306). From Myers Park, Griffith continued his real estate career with Wesley Heights in the early 1920s, but developed the Rosemont subdivision of Elizabeth and Eastover during the same period. By the 1930s, Griffith had been responsible, in some capacity, for the streetcar suburbs which encircled the city.

Development in Wesley Heights was slow initially, but as the population of Charlotte more than doubled between 1910 and 1930, real estate sales improved (Blythe, 1961: 173). In 1928, the second half of Wesley Heights was platted, extending Summit, Grandin, and Walnut Avenues across the railroad to West Morehead Street (Hanchett, 1984: 16). As part of the Wesley Heights project, Griffith focused on the development of West Morehead, which until 1927 had been a minor downtown street. By extending the street across Irwin Creek through the edge of Wesley Heights, Griffith made West Morehead an important link between downtown and Wilkinson Boulevard, the first highway in North Carolina, leading from Charlotte to Gastonia. Griffith encouraged industry to take advantage of these good transportation connections, and persuaded J.B. Duke’s Piedmont and Northern Railway to extend a spurline south to parallel the new thoroughfare (Hanchett, 1984: 17).

Wesley Heights was platted with a grid street pattern, and the lots along the principal northeast-southwest streets were long and narrow, to maximize proximity to the street rail system. House construction was determined, in part, because of the limited streetcar service, and frame bungalows predominated in the area during the l910s and early 1920s. During the late 1920s and 1930s, construction included numerous examples of one story, brick, cross gable cottages, making Wesley Heights a homogeneous neighborhood of bungalows, restrained Tudor Revival cottages, small four unit apartment houses, as well as some earlier and later exceptions to this pattern. The George Pierce Wadsworth House is one of the earliest, and perhaps only architect designed houses in this middle class neighborhood of tree-lined streets.

The changes in ownership and function of the George Pierce Wadsworth House since 1969 illustrate changes in the composition of some older Charlotte neighborhoods. The extensive urban renewal programs of the l950s and 1960s displaced large segments of the black population and put many blacks onto the housing market. In inner city neighborhoods, such as Wesley Heights, housing pressures transformed the formerly white neighborhood. By the 1970s, virtually all residents of Wesley Heights were black. The conversion of the Wadsworth House to a funeral home, after purchase by a long-standing black business family, exemplifies the metamorphosis of this residential area.

Conclusion

Designed by a well-known local architect for a wealthy patron, the George Pierce Wadsworth House breaks with the surrounding homogeneity of Wesley Heights in the size of the parcel, the layout of house and gardens, and the architectural sophistication of the house. Occupying the equivalent of three lots, the Wadsworth House is a large, two and one-half story residence in an area of relatively dense, one story bungalows and cottages. The house, large gardens (vestiges of which remain), carriage drive, and servant’s quarters form an ensemble which contrasts to the uniformly middle class composition of the surrounding area. The survival of the servant’s quarters/carriage house is rare and further underscores the contrast with later construction. Architecturally, the irregular massing, materials, and detailing make the George Pierce Wadsworth House an impressive and rare local example of the Arts and Crafts movement from the early twentieth century.

Bibliography

Bishir, Catherine. North Carolina Architecture. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1990.

Blythe, LeGette and Charles Raven Brockmann. Hornets’ Nest: The Story of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County. Charlotte: McNally of Charlotte, 1961.

Farnsworth, Julie. “Louis Asbury: Builder of a City.” Charlotte Observer, 24 March 1975.

Hanchett, Thomas W. Charlotte Neighborhood Survey: An Architectural Inventory. Volume III. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Properties Commission, November 1984.

Hubbel, C.G. Plat Map. Wesley Park, Section 1, Wadsworth Lend Company, Charlotte, North Carolina. Records of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission.

Interview with Charles McClure, 23 April 1985. Interview conducted by Barbara M. Mull. Records of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission.

Interview with Charles McClure, 29 November 1994. Interview conducted by Frances P. Alexander and Robert Drakeford, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission Member.

Mull, Barbara M. Historical Sketch of the Wadsworth-Ramsey House. April 1985. Records of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission.

Sanborn Fire Insurance Company. Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1929.