SURVEY AND RESEARCH REPORT

On The

Woodlawn Avenue Duplex

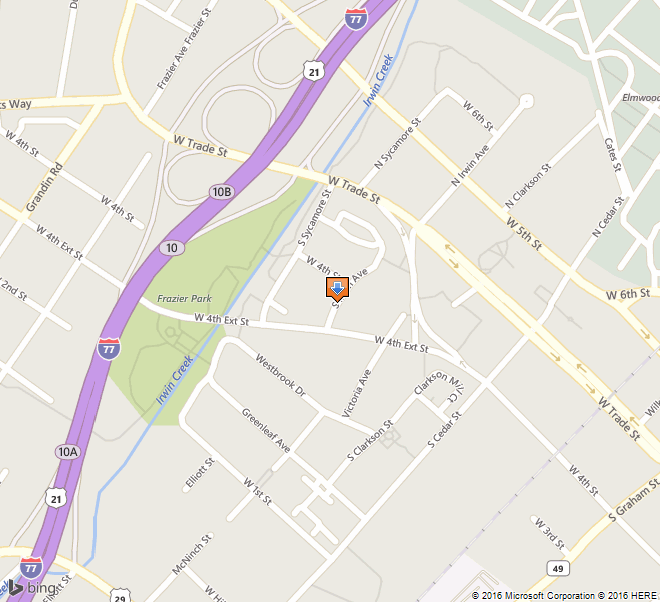

1. Name and location of the property: The property known as the Woodlawn Avenue Duplex is located at 210 South Irwin Ave, in Charlotte, North Carolina. Its UTM location is 17 513226E 3898947N

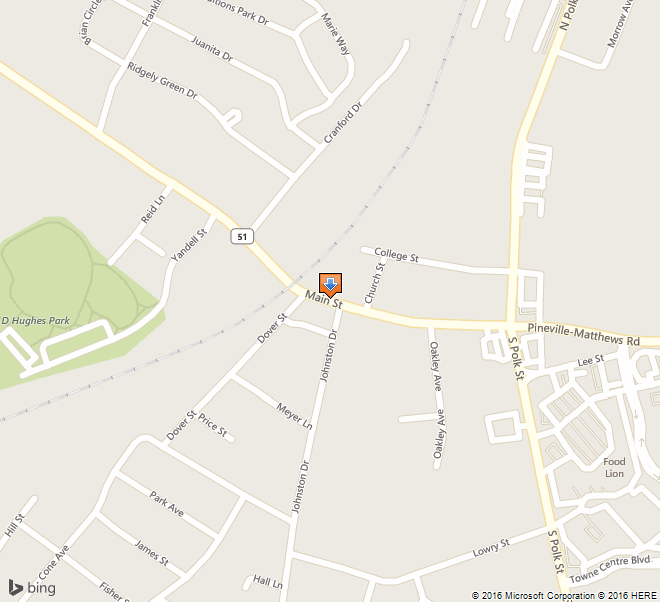

2. Name and address of the present owner of the property:

T Hardy Investment Group LLC

PO Box 621085

Charlotte, NC 28262

3. Representative photographs of the property: This report contains representative photographs of the property.

4. Maps depicting the location of the property: This report contains a map depicting the location of the property.

5. Current deed book and tax parcel information for the property:

The Tax Parcel Number of the property is 07321509. The most recent deed reference to this property is 20473-984, recorded in Mecklenburg County Deed Book

6. A brief historical sketch of the property: This report contains a brief historical sketch of the property.

7. A brief architectural and physical description of the property: This report contains a brief architectural description of the property.

8. Documentation of why and in what ways the property meets criteria for designation set forth in N. C. G. S. 160A-400.5:

a. Special significance in terms of its history, architecture, and/or cultural importance: The Commission judges that the property known as the Woodlawn Avenue Duplex does possess special significance in terms of Charlotte-Mecklenburg. The Commission bases its judgment on the following considerations:

1) The Woodlawn Avenue Duplex is a prominent reminder of the early 20th century residential nature of Charlotte, and is thus an important artifact that can help us understand the city’s built environment which has been radically altered by both the commercial development of Charlotte after World War II, urban renewal, and the recent phenomenal commercial and residential development of the Uptown.

2) The Woodlawn Avenue Duplex is a well-preserved example of a small two-story duplex, which was once a common component of the Uptown residential landscape but is now the among the rarest of the historic building types.

3) The Woodlawn Avenue Duplex demonstrates both the diversity of residential building types and the social and economic diversity that once existed in the city neighborhoods but was not found in much of the residential development in Charlotte after World War II.

4) The Woodlawn Avenue Duplex is one of the few surviving buildings that were part of Woodlawn, an early streetcar suburb.

b. Integrity of design, setting, workmanship, materials, feeling and/or association: The Commission contends that the physical and architectural description which is included in this report demonstrates that the Woodlawn Avenue Duplex in Charlotte, N.C. meets this criterion.

9. Ad Valorem tax appraisal: The Commission is aware that designation would allow the owner to apply for an automatic deferral of 50% of the Ad Valorem taxes on all or any portion of the property which becomes designated as a “historic landmark.”

Date of preparation of this report: December 2006

Prepared by: Stewart Gray

Historical Context Statement for the Woodlawn Avenue Duplex

Residential Housing in the Center City

Once largely residential, Charlotte’s urban core now contains a much-reduced collection of historic residential buildings. Due to Urban Renewal during the 1960s and 1970s, entire residential neighborhoods near the city’s urban core have been obliterated. Second Ward, which consisted of roughly a quarter of the city in the 19th century, now contains only housing in modern apartment buildings currently being constructed, The Brooklyn neighborhood occupied much of Second Ward and was once arguably the cultural center of the city’s African-American community. Today only a school gymnasium, one commercial building, and a church survive. Blandville, an African-American neighborhood that existed to the south of Morehead Street, was also negatively impacted by Urban Renewal. The building of a new expressway, warehouses, shops, and factories contributed to the conversion of the Blandville neighborhood into a strictly industrial/commercial area. Of the hundreds of homes that once populated Blandville, only one house with integrity still exists.

House on Dunbar Street in Blandville

House on Dunbar Street in Blandville

This phenomenon of neighborhood eradication in Charlotte was not limited to black neighborhoods. In the 19th Century, the homes of the city’s wealthiest and most influential citizens lined its two dominant streets, Trade and Tryon. Many of these homes survived into the middle years of the 20th century. None now exists. A collection of historic homes dating from the late nineteenth century has survived in the Fourth Ward and are part of the locally designated Fourth Ward Historic District. But outside Fourth Ward, historic residential buildings in the Urban Core are rare. The William Bratton House was built around 1923 in Charlotte’s First Ward. The home of a Duke Power engineer, it was situated amid a streetscape of single-family houses and duplexes built for middle and upper-middle class whites. Today, it is the only surviving residential building along North Brevard Street. The house, now an office, faces east on a flat lot, bordered by vacant lots and parking lots. Only one other pre-World War II home has survived in the Ward, which once featured hundreds of homes.

William Bratton House, ca. 1923

William Bratton House, ca. 1923

631 North Brevard Street

The near-complete loss of historic residential buildings in the Center City makes it difficult for the public to understand the pre-World War II history of Charlotte based on the current built environment. This scarcity of historic resources endows the surviving neighborhoods and exceptional individual buildings in those neighborhoods with special significance if they have retained their integrity.

Woodlawn Neighborhood

The development of the Woodlawn Neighborhood was part of the phenomenal growth that Charlotte experienced in the early years of the twentieth century. Between 1900 and 1910, the city’s population grew 82%, from18,091 to 34,014. In response, the city expanded physically, with its boundaries moving outward to incorporate former farmland. From 1885 to 1907, the city’s area grew 570%. This incredible growth continued with the city’s population reaching 82,675 by 1930. [1] To accommodate the new citizens, real estate developers such as F. C. Abbott, George Stephens and B. D. Heath built neighborhoods that were linked to the city by the expanding streetcar systems. [2] Some of these neighborhoods, such as Myers Park, Wilmore, and Washington Heights, have survived. Others, such as Oakhurst (now in Plaza Midwood), Piedmont Park (now part of Elizabeth), and Woodlawn (now considered part of Irwin Park or Third Ward) were absorbed into larger neighborhoods and have lost their distinct historic identities.

Woodlawn resulted from a decision by the Continental Manufacturing Company to develop its surplus land in Charlotte’s Third Ward into a residential neighborhood. Development began around 1907. Although located inside one of the City’s original four wards, the neighborhood was promoted as a suburb, perhaps due to the developing success of Charlotte’s first true streetcar suburb, Dilworth. Streetcar lines radiated out from the center of the city, and along these lines neighborhoods called “streetcar suburbs” sprang up. Woodlawn was one of these neighborhoods, and it was served by the West Trade Street streetcar line. The close-in nature of the neighborhood may have been one of its selling points. A 1911 advertisement proclaimed “Woodlawn is the nearest suburb to the business part of the city, yet NONE is prettier.” [3]

Woodlawn was never a large neighborhood. Originally platted along just four streets, it appears that soon after the small neighborhood was built it began to loose its original identity. The 1911 Sanborn Maps show the small neighborhood labeled as Woodlawn. Virginia Woolard, who grew up in the neighborhood on Grove Street in the 1940s, does not recall that her neighborhood ever had a name.[4] Instead one would simply refer to the street name to identify where they lived. Still, the original identity of the neighborhood was retained to some extent with the name of its principal street, Woodlawn Avenue. This final link to the historic name of the neighborhood was lost when the curving Woodlawn Avenue was renamed. A short street, Woodlawn Avenue never contained more than 22 buildings. In 1953 a new road named Woodlawn Road appeared in the city directory. It also contained around 20 homes. But this new road was located to the south of the city where suburban development exploded after World War II. By 1959, hundreds of new homes lined Woodlawn Road, which became a major thoroughfare feeding the city’s new suburban residential, and commercial development. The two blocks that had been labeled Woodlawn Avenue were renamed Irwin Avenue South, to avoid confusion with the robust roadway to the south.

Duplexes

The Woodlawn Avenue Apartments is a duplex with distinct upstairs and downstairs units. While some good examples of early-twentieth-century duplexes survive in the outlying suburbs of Elizabeth, Dilworth, and Plaza Midwood, the story in the city’s historic core is quite different. A survey of Charlotte’s Center City conducted by the Charlotte Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission in 2004 identified fifty-two individual properties that could potentially be designated as historic landmarks. Of these, only two were duplexes: the Woodlawn Avenue Apartments, and the North Myers Street Duplex. This low number is especially dramatic when a review of Sanborn Maps shows that duplexes, as well as quadraplexes, were a common feature in the Center City. Identified in the 2004 survey, the North Myers Street Duplex is an important reminder of the historic residential nature of First Ward. Unfortunately, the historical context of the building has been lost, as it is now the sole survivor of a residential neighborhood and is now, like the William Bratton House, surrounded by vacant lots, parking lots, and sprawling late 20th- and 21st-century commercial buildings. In contrast, the Woodlawn Apartments is located amidst a small collection of surviving single-family homes. The remnant of the Woodlawn neighborhood around the Woodlawn Apartments concretely demonstrates what the old directories and fire insurance maps indicate that duplexes and other multi-family residential buildings were commonly intermingled with single-family homes in early twentieth-century neighborhoods.

Myers Street Duplex

Myers Street Duplex

Sanborn maps from 1953 indicate that duplexes were still a common building type in the Center City landscape at least until the middle years of the 20th century. In First Ward the block formed by 8th and 9th Streets and North Brevard and Caldwell streets contained twenty-seven closely spaced residential buildings. Of those, at least 15 appear to have been duplexes. Not all residential sections contained such a high percentage of duplexes. In the city’s Fourth Ward, the block surrounded by 9th and 8th streets, Graham and Smith Streets contained 21 residential buildings with five of those being duplexes. A review of the Sanborn maps clearly indicates that nearly every single block of residential buildings in the four wards once contained duplexes.

In Charlotte, this historic housing pattern was largely abandoned after World War II when the new suburban neighborhoods were strictly segregated into either single-family or multi-family groups.

Woodlawn Avenue Duplex

Built between 1926 and 1929[5], the Woodlawn Avenue Duplex was very much part of the “everyday” architecture of Charlotte’s urban core before World War II. Blue-collar and lower level white-collar workers lived there for much of the 20th Century. In 1934, 208 Woodlawn, the upper unit of the duplex, was occupied by Harry and Mary Fine. Harry was listed as a clerk with the Southern Public Utilities Company, which later became Duke Power. Downstairs in 210 Woodlawn lived William and Frances Craig. William’s occupation is listed as Traveling Salesman. The Fines and the Craigs lived in a neighborhood principally of singles-family houses. The only other multi-family buildings in the small Woodlawn Neighborhood were the quadraplex next door and the four-unit Woodlawn Terrace Apartments. More transitory than their neighbors who generally owned their own homes[6], the tenants in the duplex were different by 1942. That year “credit manager” James Strawn lived in 208 Woodlawn and machinist Herbert Crouch and his wife Diamond lived in 210.

The Woodlawn Avenue Duplex continued to function as a duplex through the 1960s even as the nature of the neighborhood changed. Like most of Third Ward, the Woodlawn neighborhood saw an outflow of white residents as the suburbs of the city expanded. Facing a dwindling supply of housing in the city’s Urban Core, black Charlotteans moved into the once segregated Woodlawn neighborhood.

While many of the original neighborhood homes have survived, the Woodlawn Duplex is the only multi-family residential building in the neighborhood to have survived with a good degree of integrity. The neighboring quadraplex has been significantly altered, and the Woodlawn Terrace Apartments have been lost. A wider survey of Third Ward indicates that the Woodlawn Duplex is the only surviving duplex in the entire ward.

In the context of a vastly changed city, the Woodlawn Duplex is an important artifact that can help us understand the early 20th century residential nature of Charlotte. It is a prominent relic of a reduced neighborhood whose original identity has been lost. It is helpful in understanding the many small neighborhoods that were absorbed into larger ones. It is representative of a once-common housing type that that has disappeared completely from Charlotte’s center city neighborhoods.

Woodlawn Avenue Duplex

Before 2005 Renovation

Architectural Description

The Woodlawn Duplex is a two-story brick-veneered building. Although detailing is restrained, the ca. 1928 duplex appears to be a late, vernacular example of the Mission Style, with the shaped parapet and arched porch being the most distinguishing elements. The exposed rafter ends of the duplex’s porch roofs fit with the style and would have been a feature familiar to Charlotte’s builders who, up until World War II, continued to utilize elements of the Craftsman Style. Another link with the local tenacity of the Craftsman Style is the duplex’s bracketed shed-roof over the entrance. This is an element found on several Craftsman Style duplexes and quadraplexes in the fairly intact Charlotte suburbs of Dilworth and Elizabeth.

The building faces east and is four bays wide with a two-story porch centered on the façade. The lower story of the porch features two brick posts connected with segmental-arches that appear to be supported by curved boxed-in wooden lintels. In contrast to the masonry lower porch, the upper story features square wooden posts that support a built-up exposed beam that in turn supports the shed roof’s rafters. The rafter ends are fancifully sawn with double curves. The porch ceiling and in-fill walls are covered with original tongue-and-groove narrow boards.

The façade is veneered with wire-cut brick. A watertable is delineated with a soldier-course of brick resting on a solid brick foundation that has been stuccoed smooth. All exterior doors and windows have been replaced. Wall openings on the second story are aligned with those on the first. On both stories the southernmost bay contains double metal casement windows that replaced original metal casements. The windows feature simple brick sills, and soldier-courses delineate the lintels. On both stories, the porch shelters a door opening and another double-window opening. The northernmost bay contains the main entrance to the duplex. A shed roof shelters the door and is supported by two large brackets with curved braces. The rafter ends are also sawn with a single curve. The door was originally bordered with multi-pane sidelights, which have been replaced with single-light sidelights. This doorway was originally only the entrance to the upper apartment of the duplex. The original entrance to the lower apartment was accessed through the porch. Metal railing now blocks this entrance, and both apartments share a single entrance. Above the doorway is a single metal casement.

The façade features a parapet with flat and curvilinear coping. The raised center section of the parapet is highlighted with a cross pattern in the brickwork.

South Elevation

North Elevation

The side elevations lack the architectural features of the façade. The south elevation is pierced by four window openings. The north elevation is pierced by a small window opening set between the upper and lower stories that lights the stairwell.

A narrow alley runs behind the building. Sanborn maps indicate that the duplex originally had automobile parking in the basement. The bays for the auto parking are now obscured with stucco. Unlike on the other elevations, the fenestration on the rear of the building has been somewhat altered. An original short window has been infilled, and one double-window opening has been reduced to the size of a single window opening.

[1] Dan Morrill “Center City Housing” http://landmarkscommission.org/uptownsurveyhistoryhousing.htm

[2] Tom Hanchett “The Growth of Charlotte: A History” http://www.cmhpf.org/educhargrowth.htm

[3] Ibid

[4] Conversation with Virginia Woolard, October 2006. Notes on file with the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission.

[5] The building is not listed in the 1926 City Directory, but does appear in the 1929 Sanborn Maps.

[6] Home ownership indicated in 1942 City Directory.

Survey and Research Report

on the

Woodlawn Bungalow

1015 West Fourth Street, Charlotte

1. Name and location of the property: The property known as the Woodlawn Bungalow is located at 1015 West Fourth Street, Charlotte, North Carolina.

2. Name and address of the current owner of the property:

The Committee to Restore and Preserve Third Ward

1001 West First Street

Charlotte, NC

3. Representative photographs of the property. This report contains representative photographs of the property

4. A map depicting the location of the property.

Mecklenburg County Tax Map

5. Current Deed Book Reference To The Property. The most recent deed to this property is found in Mecklenburg County Deed Book 9443, page 998. The tax parcel number for the property is 07321513.

6. A Brief Historical Essay On The Property. This report contains a brief historical sketch of the property prepared by William Jeffers.

7. A Brief Physical Description Of The Property. This report contains a brief physical description of the property prepared by Stewart Gray.

8. Documentation of why and in what ways the property meets the criteria for designation set forth in N.C.G.S. 160A-400.5.

a. Special significance in terms of its history, architecture, and/or cultural importance. The Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission judges that 1015 West Fourth Street possesses special significance in terms of Charlotte-Mecklenburg. The Commission bases its judgment on the following considerations:

1) The Woodlawn Bungalow is a remarkably well preserved example of a Craftsman Style bungalow, typical of the type of house that was constructed for middle class residents of Charlotte in the city’s urban core for a brief period of time in the early 1900s.

2) The Woodlawn Bungalow may very well contain the most complete and best preserved Craftsman Style bungalow interior in the City of Charlotte.

3) The Woodlawn Bungalow is an important element of Woodlawn, an early streetcar suburb, and is a reminder of the early 20th century residential nature of Charlotte’s urban core

b. Integrity of design, setting, workmanship, materials, feeling and/or association: The Commission judges that the physical description included in this report demonstrates that the property known as The Woodlawn Bungalow meets this criterion.

9. Ad Valorem Tax Appraisal: The Commission is aware that designation would allow the owner to apply for automatic deferral of 50% of the Ad Valorem taxes on all or any portion of the property which becomes a designated “historic landmark”. The current appraised value of the Woodlawn Bungalow meets Street is $185,500. The property is zoned UR-1.

10. Portions of the property recommended for landmark designation: This report finds that the interior, exterior, and land associated with the Woodlawn Bungalow should be included in any landmark designation of the property.

Date of preparation of this report:

June 1, 2011

Prepared by:

William Jeffers and Stewart Gray

Third Ward Contextual History

Until the twentieth century, Charlotte’s urban core was a mix of residential and commercial structures. The most influential of the city’s population clustered along the two main thoroughfares of Trade and Tryon Streets while businesses and commercial structures were interspersed between them. This pattern had been the norm, more or less, since the town’s founding. However, as the twentieth century dawned, Charlotte began to undergo a transformation from a quiet courthouse town to a burgeoning metropolitan city. As a result, the residential patterns of the urban core began to change in ways that would redefine the built landscape of the center city.

Charlotte was organized along a ward system. Initially divided into four numerically named wards, each had a sizable collection of residential housing. As the twentieth century progressed this collection of residential dwellings began to take a backseat to the industrial and commercial development that overtook the core. This phenomenon is typified in the development of streetcar suburbs like Dilworth, and in the creation of the mill village of North Charlotte. These new neighborhoods began to draw both the affluent and working class residents out of the center of town to points that then were clustered around the periphery of the city. This transformation, however, did not occur overnight and each ward was affected differently by it. Fourth Ward retained a strong residential pattern still evident today. First and Second Ward also had a large number of residential housing. However, both of these wards have lost much of their historical integrity. This is painfully evident in Second Ward, where Urban Renewal destroyed the African American community of “Brooklyn,” eliminating all the residential structures of the neighborhood.

Third Ward, like the other wards around it, also contained a combination of residential and commercial structures. However, “what is now considered Third Ward is made up of two very separate areas.”[4] The original section of Third Ward was an area that was bordered by, Morehead Street, Graham Street West, and Trade and Tryon Streets.[5] This section of Third Ward followed residential patterns similar to First Ward with a mixture of residential and commercial uses with fewer black residences.[6]

The arrival of the Piedmont and Northern Railroad in the second decade of the twentieth century, precipitated a shift in land use in this ward; so much so that “the area became the least residential of the four wards, with warehousing and commercial uses as its heart and industry on Graham Street along the Southern Railway tracks.”[7]

Following the patterns of other city wards, the edges of Trade and Tryon Streets contained commercial development. This section of Third Ward, while lacking in residential structures, had several significant industrial and commercial structures such as the now demolished Good Samaritan Hospital (Bank of America Stadium currently resides on the property) and the demolished Piedmont and Northern Railroad depot. This large railroad terminal, which precipitated the transformation of the ward towards industry, has also succumbed to the wrecking ball. James B. Duke, president of both the utility company and the railroad, first utilized the site for the headquarters of the Piedmont and Northern. Eventually, he expanded the structure, building the “headquarters for Duke Power at the front of the lot in 1928.”[8] Another example is the no longer extant Charlotte Supply Building. Built in1924-1925, the Charlotte Supply Building was a supplier of textile machinery and served as “a well preserved warehouse building of the type that the railroads attracted to Third Ward.”[9]

Extant examples exist in the United States Post Office Building on West Trade Street. The massive structure, with its signature limestone columns, was built in 1915.[10] Another is seen in The Virginia Paper Company building on West Third Street. Constructed in 1937, the building serves as a largely unaltered example of industrial architecture from the 1930’s and also underlines the wards transition from residential/commercial to an industrial area.[11]

Woodlawn Neighborhood

The second section of Third Ward is the residential area between the Southern Railway railroad tracks and Interstate 77. This area remained undeveloped during much of the city’s early history.[12] The first structure built in this section was the Victor Cotton Mill (no longer extant). Constructed in 1884, the mill was located near the intersection of Clarkson Street and Westbrook Drive.[13] Around 1907 the owners of the mill, by then known as the Continental Manufacturing Company, began to develop the surplus land it owned in Third Ward into the neighborhood of Woodlawn through a subsidiary known as the Woodlawn Realty Company.

“The Development of the Woodlawn Neighborhood was part of the phenomenal growth that Charlotte experienced in the early years of the twentieth century. Between 1900 and 1910, the city’s population grew 82%, from 18,091 to 34, 014.”[14] As a result, the physical boundaries of the city began to expand out from the original four wards. In order to accommodate these new citizens real estate developers such as F.C. Abbott, George Stephens, and B.D. Heath built neighborhoods that were linked to the city by the expanding streetcar systems.[15]

The Woodlawn Neighborhood was one of these new streetcar suburbs. While located inside one of the city’s original four wards, the neighborhood was advertised as a suburb, perhaps due to the developing success of Charlotte’s first true streetcar suburb, Dilworth.[16] With streetcar lines radiating outward from the center of town, new neighborhoods began to develop along the lines. Woodlawn was one such neighborhood, and it was served by the West Trade Street streetcar line.[17] The fact that the neighborhood was situated so close to downtown may have been a marketing tool for local developers. An advertisement in the October, 10, 1911 Charlotte Observer proclaimed that “Woodlawn is the nearest suburb to the business part of the city, yet NONE is prettier.”[18] Many of the original parcels of land in Woodlawn were bought by J.W. McClung, a realtor who office was located at 25 South Tryon Street[19] McClung also lived in the Woodlawn Neighborhood[20]

The Woodlawn Bungalow

The Woodlawn Bungalow, located at 1015 West Fourth Street, is an exemplary example of a Craftsman Style bungalow. It is remarkably well preserved, having retained nearly all of its original significant architectural features. The exterior is largely original with only sensitive changes on the rear to allow for better disabled accessibility. The interior of the Woodlawn Bungalow is remarkably well preserved. The interior has retained an extremely high degree of integrity and is in good condition. The ca. 1909 layout of the interior remains virtually intact. All of the original significant interior architectural features have survived intact, and no significant interior alterations have occurred. The Woodlawn Bungalow may very well contain the most complete and best preserved Craftsman Style home interior in the City of Charlotte. The well preserved exterior combined with the exceptional interior imbues The Woodlawn Bungalow with significance as an important artifact of the Woodlawn neighborhood, but also as an important historical architectural asset for the City of Charlotte.

The bungalow form can trace its origins to India. The house form inspired American architects in the creation of the Craftsman Style house. The bungalow form and elements of the Craftsman Style became phenomenally popular in America in the early years of the twentieth century, and continued to be extensively utilized until the advent of the Great Depression. The bungalow was extremely popular in the American South. One factor in this popularity was that the bungalow form, with its wide eaves and ample porch, was suitable for hot weather.

The Craftsman Style and the bungalow form were enthusiastically embraced by Charlotte builders during the booming years of the early twentieth century. While the bungalow was particularly suited for warm weather, it was also suited as a design for smaller middle class homes. With the ability to combine style, convenience, simplicity, solid construction, and plumbing with a modest construction cost, this type of residence helped many in the early twentieth century achieve the dream of home ownership. As a result, the Craftsman Style bungalow would become the preferred house for many middle class residents of Charlotte.

The Woodlawn Bungalow was built sometime between 1909 and 1910. While no building permit could be found giving the exact date, Charlotte City directories list Oscar and Katie Hunter as its first residents in 1910.[22] The house seemed to have a high degree of turnover, because the 1911 directory lists Locke S. Sloop, a bookkeeper with Charles Moody Company (located at 25 – 31 South College Street)[23], and his wife Nelle as the new residents.[24] In 1914, J.W. Baynard, a superintendent at F.S. Royster Guano Company (located at 200 South Tryon Street in the Commercial National Bank Building),[25] and his wife Marie[26] lived at the house and would do so until 1920 when J.L. Dew took up residence.[27] This pattern of residential turnover would continue to be the norm for the Woodlawn Bungalow. Between the years 1926 – 1943, Charlotte city directories list no fewer than six different tenants at the address.[28]

The high residential turnover rate at the Woodlawn Bungalow may reflect a rapid change in the neighborhood’s character. By the 1920s the city directories, which generally list the occupations of the residents, demonstrates a significant change in the nature of the neighborhood. Woodlawn had by the 1920s the city directories, which generally list the occupations of the residents, demonstrate a significant change in the nature of the neighborhood. Woodlawn had by the 1920s become less middle class and more working class. Even though J.W. Baynard was solidly middle class as the superintendent of a large company, the professions that populated the street and the neighborhood at large. By the 1920s, painters, salesmen, secretaries, and county policemen (to name a few), were distinctly working class.[29] Virginia Woolard, a childhood resident of Woodlawn stated: “We were working families, we just worked and worked. Our lives were not dramatic; it was just the everydayness of things. We went to church, went to school, and sort of minded your own business.”[30]

Woodlawn, as a neighborhood, never grew past its original layout. It was built as a white middle class community. Early deeds confirm as much stipulating that all lots “shall be used for resident purposes and by people of the white race only (a common stipulation in the Jim Crow South); and that no dwelling shall be erected thereon which shall cost less than $1000.00.”[31] Plotted initially along four streets, it appears that soon after the small neighborhood was built it began to lose its original identity.[32] Sanborn Maps show the neighborhood listed by the name Woodlawn. Virginia Woolard, however, recalled that she never knew of the area specifically as “Woodlawn.” Generally, people would refer to the street on which they lived as a geographic reference rather than using a neighborhood moniker.[33] As she stated, “when I was growing up I was not aware of the word ‘Woodlawn.’ I didn’t have any concept about any name where we lived.”[34]

Still, there was a sense of community amongst the residents of the area. One of the reasons for this was the fact that the neighborhood was pedestrian friendly. Trade Street was the only main thoroughfare in the neighborhood. Many of the other streets ended at Irwin Creek and were devoid of heavy traffic. As a result people moved around the neighborhood freely. As Virginia Woolard related, “I enjoyed visiting, we would go back and forth between each other’s houses.”[35] The neighborhood had an abundant tree canopy and considering its proximity to downtown Charlotte one “had the sense that you were somewhat isolated” from the rest of the city because of it.[36]

Eventually, this sense of community became eroded. It began with the renaming of Woodlawn Avenue to South Irwin Avenue. This was done due to new development outside the city center along the new Woodlawn Road and the name change would help, “to avoid confusion with the robust roadway to the south.”[37] Furthermore, office and commercial zoning that were arbitrarily put in place along the thoroughfares rendered many existing residences obsolete. By the 1970s with the construction of new roads, the neighborhood was opened up to heavy vehicular traffic, destroying the “walkable” feel of Woodlawn’s original design. As the neighborhood lost its identity, coupled with an explosion in suburban construction in the postwar decades of the 1950’s and 1960’s, a steady decline ensued. As middle class families began to leave the neighborhood, it gradually became populated by working class families, some of whom had left the Brooklyn and First Ward neighborhoods as a result of Urban Renewal programs.[38]

After Urban Renewal parts of Third Ward, including Woodlawn, were considered some of the city’s worst neighborhoods, “populated with liquor houses and ‘fancy houses’ for prostitutes.”[39]

After Urban Renewal parts of Third ward, including Woodlawn, were considered some of the city’s worst neighborhoods, “populated with liquor houses and ‘fancy houses’ for prostitutes.”[39] The Ward, however, would experience a renaissance. In 1975, Third Ward was designated as a community Development Target Area. Under that program Third Ward benefited from housing rehabilitation, as well as street, sidewalk, landscaping and park improvements.[40] Another key to the revival was the removal of a metal scrap yard between South Cedar Street and the railroad tracks.[41] New residential development along Cedar and Clarkson Streets, as well as other small scale projects served as further catalysts for this transformation.

Even with all this new development, the Woodlawn neighborhood of Third Ward still retains much of its original historic integrity; well representing an early twentieth century, middle class Charlotte neighborhood. As Dr. Thomas Hanchett points out in his study of Charlotte’s urban core for the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission, the Woodlawn section contains, “one of Charlotte’s notable concentrations of early bungalows. The small frame houses lining Grove and West Fourth Streets between Sycamore and Irwin create a streetscape that today looks much as it did seventy years ago.”[42] Unfortunatly, across Trade Street in Fourth Ward, a large number of bungalow style houses like the ones in Woodlawn have recently fallen victim to the wrecking ball. The Woodlawn neighborhood represents the apex of center city, middle class, residential construction in the early twentieth century. By the 1920’s, middle class residential building trends had shifted away from the center city to residences like the Radcliffe-Otterbourg House in Colonial Heights and Middleton Homes. Therefore, the near complete loss of historic residential buildings in the Center City makes it difficult for the public to understand the pre-World War II history of Charlotte based on the current built environment.[43] This dearth of historic residential resources in Charlotte’s urban core gives the surviving neighborhoods, and individual structures within them, historic significance if they have retained their original integrity. Considering the fact that Charlotte has excellent preserved examples of the upper class experience in Fourth Ward, Eastover, and Myers Park; coupled with the white, working class experience of the North Davidson community and the African American experience in communities like Cherry, the importance of highlighting Charlotte’s middle class experience becomes even more paramount. The Woodlawn Bungalow was restored in 2010 by the Committee to Restore and Preserve Third Ward. The house was named the Baxter-Polk House by the neighborhood committee in honor of educator and neighborhood leader Dr. Mildred Baxter Davis and James K. Polk, a leader in minority affairs in Charlotte. Local landmark designation of the Woodlawn Bungalow can serve as a starting point to rectify this imbalance.

[1] See CMHLC, Old House Style Guide, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission, http://www.cmhpf.org/kids/Guideboox/OldHouseGuide.html, (Accessed April 12, 2011).

[2] Dan L. Morrill, A Walking Tour of Elizabeth, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission, http://www.cmhpf.org/educationwalkelizabeth.htm, (Accessed May 10, 2011).

[3] See Morrill, A Walking Tour of Elizabeth, and CMHLC, Old House Style Guide.

[4] Dr. Thomas W. Hanchett, The Center City: The Business District and the Original Four Wards, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission, http://cmhpf.org/educationneighhistcentercity.htm (Accessed April 10, 2011).

[5] See Hanchett, The Center City.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Hanchett, The Center City.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] See Hanchett, The Center City.

[11] See CMHLC, Survey and Research Report on The Virginia Paper Company Building, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission, http://cmhpf.org/SurveyS&RVirginia.htm, (Accessed June 8, 2011).

[12] See Hanchett, The Center City.

[13] Third Ward Neighborhood Association, The Committee to Restore and Preserve Third Ward, and the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Planning Commission, A Third Ward Future: A Land Use & Urban Design Plan for an Uptown Charlotte Neighborhood, Volume 1, July 1997, p. 7.

[14] Stewart Gray, Survey and Research Report on the Woodlawn Avenue Duplex, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission, http://cmhpf.org/SurveyS&RWoodlawn.htm, (Accessed April 10, 2011).

[15] See Gray Woodlawn Avenue Duplex.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Charlotte Observer, October 10, 1911.

[19] See Ernest H. Miller, Charlotte City Directory, 1911, (Asheville, N.C.: Piedmont Directory Company, Inc., Publishers, 1911) p. 283.

[20] See Ernest H. Miller, Charlotte City Directory, 1912, (Asheville, N.C.: Piedmont Directory Company, Inc., Publishers, 1912) p. 294.

[22] See Ernest H. Miller, Charlotte City Directory, 1910, (Asheville, N.C.: Piedmont Directory Company, Inc., Publishers, 1910) p. 126.

[23] See Ernest H. Miller, Charlotte City Directory, 1911, (Asheville, N.C.: Piedmont Directory Company, Inc., Publishers, 1911) p. 307.

[24] See Ernest H. Miller, Charlotte City Directory, 1911, p. 523.

[25] See Ernest H. Miller, Charlotte City Directory, 1914, (Asheville, N.C.: Piedmont Directory Company, Inc., Publishers, 1914) p. 178.

[26] See Miller, Charlotte City Directory, 1914, p. 626.

[27] See Ernest H. Miller, Charlotte City Directory, 1920, (Asheville, N.C.: Piedmont Directory Company, Inc., Publishers, 1920) p. 790.

[28] See the 1926, 1933, 1934, 1938, 1939, and 1943 Volumes of Hill’s Charlotte City Directory, (Richmond, VA: Hill Directory Co., Inc., Publishers).

[29] Ibid.

[30] Bill Jeffers, Interview with Virginia Woolard.

[31] Mecklenburg County Deed Book 241, p. 486.

[32] See Gray, Woodlawn Avenue Duplex.

[33] See Stewart Gray, Conversation with Virginia Woolard, October 2006. (Notes on file with the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission).

[34] Bill Jeffers, Interview with Virginia Woolard, May 2011.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Gray, Woodlawn Avenue Duplex.

[38] See Third Ward Neighborhood Association, A Third Ward Future, p.7.

[39] Gail Smith, “3rd Ward, Voices of Vision,” Mecklenburg Neighbors, July 22, 1989, p. 12.

[40] See Third Ward Neighborhood Association, A Third Ward Future, p.7.

[41] See Gail Smith, Mecklenburg Neighbors, p.13.

[42] Hanchett, The Center City.

[43] See Gray, Woodlawn Avenue Duplex.

ARCHITECTURAL DESCRIPTION

1015 West Fourth Street is a ca. 1909 one-story front-gabled Craftsman Style bungalow that faces north and is set back approximately 30’ from the granite curbed street. The neighborhood is a mix of single family houses and small multi-family residential buildings. Like 1015, most of the buildings in the neighborhood date from the first half of the 20th century. This portion of West Fourth Street slopes steeply to the west, following the contour of the land which leads down to Irwin creek. Along this street and in mush of the neighborhood all of the houses are set close to the street and close to the neighboring houses. In some instances the houses are separated by as little as 10’. The neighborhood is dominated by mature oak trees. Sidewalks line most of the streets, and alleys run behind many of the lots.

The front elevation is dominated by a substantial front gable that projects over a recessed porch. A rebuilt continuous brick foundation is interrupted by four tall brick piers topped with simple concrete caps. The piers are spaced evenly across the front elevation. Between the easternmost piers, a wide set of brick steps is flanked by cheek walls topped by simple concrete caps. Between the other front piers, the foundation is pierced by large wood louvered vents. A wooden floor with a simple wood band is supported by the masonry porch foundation. The tall piers are connected by balustrades composed of original chamfered top rails and simple original narrow balusters.

The piers are topped by Craftsman Style tapered posts. The posts rest on simple wooden bases with cavetto trim. The posts are topped with simple wooden caps with cavetto trim. The posts support a boxed beam with a narrow band of cyma recta moulded trim. Above the boxed beam are a row of simple modillions bordered on the bottom by cyma trim. The modillions are separated by deep cyma trim. The modillions and trim project slightly forming a shallow pent. The gable is covered with wood shingles that angle out to cover the pent, giving the gable wall a bell-cast shape.

The gable is pierced by a window opening that contains a pair of fixed nine-light sash bordered on each side by louvered vents. The gable is sheltered by a deep roof overhang supported by decoratively sawn brackets. The soffit is sheathed with beaded boards. Although compromised over the years as roof sheathing has been replaced, the original profile of the gable included a bell-cast design over the eaves.

Sheltered by the deep overhangs, all of the architectural elements of the front porch, with the exception of the wood flooring, have survived intact. The porch elevation contains two bays. The east bay contains a wide single-light door. The door also features two horizontal raised panels. The door opening features an early, if not original, screen door. The door is bordered on each side by fixed single-light windows. The relatively short windows are set flush with the top of the door. The other bay contains a set of three one-over-one windows. The original windows feature simple trim and sills. The porch features simple clapboards used on all of the exterior walls. The courses of clapboards terminate in corner boards with a moulded round-over detail. The clapboards on the porch are topped by two-wide wide frieze boards. The horizontal joint between the boards is covered by narrow cyma trim. The porch wall is topped with more narrow cyma trim. The porch ceiling is beaded board.

The west elevation contains six window openings. From the front, the first two bays are small nine-light fixed sash set high in the wall. These windows border an interior fireplace, and this design element was common in Craftsman Style houses. A simple bay roughly centered on the west elevation projects slightly and contains two tall one-over-one windows. The projecting bay features corner boards. To the rear of the projecting bay, two one-over-one windows are ganged together. The rearmost section of the west elevation appears to be a rear porch that has been enclosed. On this section the drip cap angles down to the rear, indicating a sloping porch floor. A single small nine-light window is set high in the wall, and may have been moved there from another location on the house. The clapboards on the east, west and rear elevations rise from a drip cap that rests on a simple water table board. The eaves on the east, west and rear elevations feature a beaded-board soffit, now retrofitted with small vents.

While 1015 exhibits a very high overall degree of integrity, the rear is the most altered elevation. Original fenestration is limited to a single small nine-light window set high in the wall. To the east of the original window, a modern wooden double-door has been added. The rear wall of the enclosed porch features a modern wooden glazed panel door. A large recent wooden deck with an integrated accessible ramp extends from the rear elevation. The rear elevation is topped with a hipped roof. The bell-cast element is more distinct on the rear sections of the roof. The roof is pierced by three thin and simply corbelled internal chimneys, all of which have been rebuilt to some extent. Though rebuilt, they match the style and scale of the chimneys on the neighboring houses.

The east elevation features a shallow projecting bay containing three one-over-one windows. The rearmost is slightly shorter than the others on the elevation, but appears to be original. To the rear and to the front of the projecting bay the east elevation is pierced by single one-over-one windows.

Interior

The interior of 1015 West Fourth Street is remarkably well preserved. The interior has retained an exemplary degree of integrity and is in good condition. The ca. 1905 layout of the interior remains virtually intact. All of the original significant interior architectural features have survived intact, and no significant interior alterations have occurred. 1015 West Fourth Street may very well contain the most complete and best preserved Craftsman Style home interior in the City of Charlotte.

The interior of 1015 features a foyer separated from a front living room by portions of a wood panel half-height wall topped with tapered post and pilasters. The living room features a stained oak mantle surround that incorporates a three-door stained glass cabinet and a recessed mantle shelf supported by modillion brackets. The firebox surround and hearth are covered with original green glazed tile. The living room and foyer feature picture molding. All of the original rooms feature plaster walls and ceilings, narrow-board pine floors, tall baseboards with a molded cap, and molded crown trim. All windows and doors are bordered by fluted jam trim, and feature moulded casing caps. Door trim features starter blocks. The living room, foyer, and the house’s two bedrooms all feature picture moulding.

The dinning room is accessed from the living via a pair of six-horizontal-panel doors. The house features numerous built-in cabinets. The largest is a built-in china cabinet in the dining room. It features a curved-sawn shelf, two raised panel doors and two glazed doors, and two drawers with original pulls. The cabinet is border by the same trim used around the doors. The dining room also features a plate rail that runs the perimeter of the room.

The two bedrooms feature six panel doors with original hardware.

The integrity found in the front, more public rooms is also found in the house’s secondary spaces. The bathroom features the original sink, bathtub, and medicine cabinet. The original tile floor was replace with a tile floor of the same design. The toilet was replace with a modern toilet.

In the kitchen the original pine floor has been preserved. The room features a short six-horizontal-panel pantry door, and two large built-in cabinets with glazed doors. The cabinets are located over the original sink, which is supported by a new cabinet base, and is surrounded by a new tile surround.

The rear hall features the same sophisticated trim found in the other rooms. A recessed fuse box is covered by a panel door, and features the same trim installed around windows. Below the fuse box is short door with a grill.

The enclosed rear porch features clapboard siding on the walls. The flooring of the enclosed porch is a collection of various width pine and oak boards.

1. Name and location of the property: The property known as the W.P.A. / Douglas Airport Hangar is located at 4108 Airport Drive in Charlotte, N.C.

1. Name and location of the property: The property known as the W.P.A. / Douglas Airport Hangar is located at 4108 Airport Drive in Charlotte, N.C.

2. Name, address and telephone number of the present owner of the property: The owner of the property is:

City of Charlotte

600 E. 4th Street

Charlotte, NC 28202-2816

Telephone: 704-336-2241

3. Representative photographs of the property: This report contains representative photographs of the property.

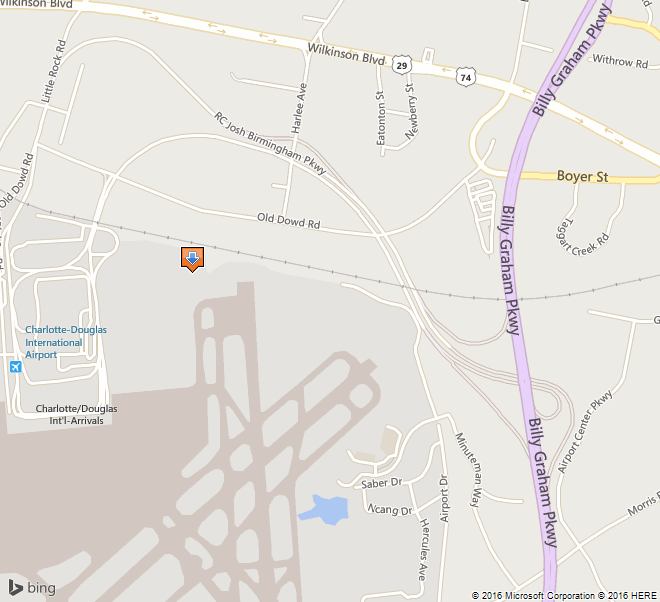

4. A map depicting the location of the property: This report contains a map depicting the location of the property. The UTM coordinates are 17.506000.3905000.

5. Current Deed Book Reference to the property: The writer of this report was unable to find the most recent deeds to this property. The tax-parcel ID is 11522102a-005.

6. A brief historical sketch of the property: This report contains a brief historical sketch of the property prepared by Ryan L. Sumner.

7. A brief architectural description of the property: This report contains a brief physical description of the property prepared by Ryan L. Sumner.

8. Documentation of how and in what ways the property meets the criteria for designation set forth in N.C.G.S. 160A-400.5:

a. Special significance in terms of its historical, prehistorical, architectural, or cultural importance: The Commission judges that the property known as the W.P.A. / Douglas Airport Hangar does possess special significance in terms of Charlotte-Mecklenburg. The Commission bases its judgment on the following considerations:

1.) The Hangar, erected in 1936—1937 by the Works Progress Administration, was intimately tied to a federal work program that preserved Charlotteans’ skills and self-respect during a period of massive unemployment.

2.) This airport was the W.P.A.’s largest project, in allotment of funds, at the time in North Carolina.

3.) Of the original five structures built by the W.P.A. at the airport, only the hangar is extant.

4.) The establishment of the airport contributed greatly to physical and economic development of the city, ever expanding to supply comprehensive and convenient air transport to Charlotte.

b. Integrity of design, setting, workmanship, materials, feeling, and/or association: The Commission contends that the physical description by Ryan L. Sumner, which is included in this report, demonstrates that the essential form of the W.P.A. / Douglas Airport Hangar meets this criterion.

9. Ad Valorem Tax Appraisal: The Commission is aware that designation would allow the owner to apply for an automatic deferral of 50% of the Ad Valorem taxes on all or any portion of the property that becomes a “historic landmark.” The current appraised value of the 502.52 acres of land is $32,834,660. There are multiple improvements on this parcel—the current appraised value of the Hangar is $82,090, while the total improvements are valued at $147,437,660. The total current appraised value is $180,272,320. The property is zoned I-1and I-2.

10. Portion of the Property Recommended For Designation: The interior and exterior of the building and a sufficient amount of land to protect its immediate setting.

Date of Preparation of this Report: May 15, 2002

Prepared by: Ryan L. Sumner

Assistant Curator

Levine Museum of the New South

200 E 7TH St.

Charlotte, NC 28202

Telephone: 70.333.1887 x226

Historical Background Statement

Ryan L. Sumner

April 25, 2002

Summary Paragraph:

The W.P.A. / Douglas Airport Hangar (“the hangar”), erected in 1936—1937 by the Works Progress Administration, was tied to a federal work program that preserved Charlotteans’ skills and self-respect during the Great Depression. Of the original structures built by the W.P.A. at the airport, only the hangar is extant. During the Second World War, when the airport was dominated by Morris Field, the hangar serviced and stored planes for the civilian flights in and out of Charlotte. As the economy grew in the post-war years, so did the airport, which built bigger and more modern repair facilities. The hangar was leased to small chartered flight organizations until the mid-1980s when it was abandoned and fell into disrepair. The building of the airport contributed greatly to physical development of the city, expanding throughout its history to serve the air transport needs of the city.

Context and Historical Background Statement

Prior to the building of Douglas Airport, flights in and out of Charlotte were rare. The Queen City’s only airfield was Charlotte Airport (later known a Cannon airport), a small private venture operated by Johnny Crowell, a famed Charlotte aviator. Although this landing strip was christened amid much fanfare as an airmail stop on April 1, 1930,1 with passenger service from Eastern Air Transport (later Eastern Airlines) following a few months later, the field was only open on weekends, for air shows, and war-pilot training.

For Charlotte Mayor Ben E. Douglas, this inadequate air operation did not fit his vision for Charlotte, which could not grow “without water and transportation.”2 In an era when commercial flight was relatively new, Douglas continually pushed for a major municipal airport to serve the area.3 Douglas convinced prominent Charlotteans of the necessity of an airport, gradually building up a base of support. In the summer of 1935, the Chamber of Commerce appealed to the City Council to provide adequate passenger and airmail service to and from the city.4

On September 3, 1935, Mayor Douglas led the Charlotte City Council in authorizing the City Manager to file an application with the Works Progress Administration for funding to build an airport.5 The application was approved and on November 13, 1935, the council voted to divert funds in order to facilitate the purchase of land for the airport site and to repay the transfers upon the sale of airport bonds.6 The bonds were sold on March 1, 1936.7

The Works Progress Administration (W.P.A.), created by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1935, is considered the most important New Deal work-relief agency. The W.P.A. developed programs to create work during the massive national unemployment and economic devastation created by the Depression. From 1935 to 1943, the W.P.A. provided approximately eight million jobs at a cost of more than eleven billion dollars and funded the construction of hundreds of thousands of public buildings and facilities. By the end of 1939, 125,000 North Carolinians who were “caught between the grindstones of a maladjusted economy” had sought gainful employment from the state’s 3984 Works Progress Administration projects.8

FDR visiting Charlotte, September 1936

From the National Archives and Records Administration

Groundbreaking, 1935

From Charlotte / Douglas International Airport Archives

Construction began in December 1935 under the direction of N.C. W.P.A. director George Coan and John Grice, Charlotte Regional W.P.A. Director.9 Hundreds of unemployed men, bundled in overcoats, stood in line for the first W.P.A. jobs, which consisted of clearing the site of trees and underbrush. One hundred and fifty of those men found work on the airport the first day.10 Many of those present had no means of transportation and walked six or more miles to the airport site.11 The Charlotte airport project grew into the W.P.A.’s largest project, in allotted funds, until that point; W.P.A. funds accounted for $323,889.47, which were combined with an investment by the City of Charlotte $57,703.28. Of this money, $143,334.96 was paid in salary to the workers on the site.

When W.P.A. construction ceased in June 1937, the new Charlotte Municipal Airport boasted an administration/terminal building, a single hangar, beacon tower, and three runways—two 3000 feet-long landing strips and one 2,500 strip, each 150 feet wide.12 The following year, the U.S. Department of Commerce added a “Visual-type Airway Radio-beam” system and a control building, which allowed pilots to engage in blind flying and blind landing.13 Of these structures, only the Hangar remains.

The City Council wasted no time putting the new airport to use. They appointed an airport commission, chaired by William States Lee, Jr. to operate the new facility. Eastern Airlines flew the first plane into the new airport on May 17. Six daily flights took off from Charlotte Municipal Airport in its first year of operation; by 1938, the number of flights increased to eight. In 1940, the city officially dedicated the site, “Douglas Municipal,” in honor of the mayor who spearheaded the movement to built the airport.

The Recently Completed Municipal Airport

Collection of the Levine Museum of the New South

North Carolina Aviator, 1935

Collection of Piedmont Airlines Historical Society

Douglas Airport saw significant expansion by the federal government beginning in 1941, when the City of Charlotte leased the airport to the War Department for an indefinite period for a nominal fee.14 Between January and April of that year, the Army Air Corps oversaw the construction of Charlotte Air Base, a military installation built to the south of the Douglas Municipal site, adjoining the runways. The military acquired additional land for the project, lengthened and widened the runways; they built a huge hangar-repair facility, a hospital, reservoir, shops, barracks, and over ninety other structures.15 The air base was renamed Morris Field, shortly after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. In May 1946, the War Assets Corporation conveyed the property back to the City of Charlotte, after investing more than five million dollars in the site.

Female workers repair a plane at Morris Field during WWII

Carolinas Historic Aviation Commission

Contrary to what some Charlotte historians have written, commercial air travel did not cease during the Charlotte Air Base or Morris Field days. Civilian passengers continued to emplane from the municipally operated terminal with little reduction in daily flights.16 The hangar built by the W.P.A. steadfastly serviced and sheltered civilian planes throughout the war.

New Terminal designed by Walter Hook, dedicated 1954

Collection of Levine Museum of the New South

In the prosperous days following World War II, the airport commission began to work on a new terminal for the epicenter of the “Sun-belt Boom.” Scheduled airline service increased rapidly from eight flights per day in 1939, to thirty flights per day in 1949.17 The new terminal, built from concrete, steel, glass and brick, epitomized the modern movement that was sweeping the country at that time. The original terminal, with its stucco walls and tin roof, didn’t fit this new paradigm; it was torn down about 1968.18

Modern hangars and repair facilities accompanied the airport expansions of the fifties and 1980s, relegating the hangar built by the W.P.A. to second-class status. The airport began to use the hangar for “fixed base operations,” and leased it to small outfits that chartered private planes for flight training and cargo transport. The hangar’s last tenant was Southeast Airmotive, which vacated the building in 1985.

The Hangar while leased by Southern Airmotive, c. 1980s

From the Charlotte Observer

As a result of neglect and Hurricane Hugo, Charlotte’s last original airport building had fallen into a state of great disrepair by the early 1990s. Nearly all the windows were smashed and the doors damaged. The structure was overgrown with kudzu. The hangar was filled with several years worth of scrap and general aviation junk, while a thirty-foot mound of hurricane-related debris was piled against the outside. The Airport slated the building to be razed.19

Aviation historian Floyd Wilson met with Airport Director Jerry Orr, and convinced him to spare the building and allow it to be turned into a museum. In 1991, Wilson formed the Carolinas Historic Aviation Commission (CHAC) and held several successful fund-raisers to restore the hangar.20 Under Orr’s direction, the airport provided a security fence, replaced the broken glass, sandblasted and repainted the walls, and repaired the doors to working order.21 Today CHAC operates the facility as the Carolinas Aviation Museum, displaying a wide variety of aircraft, plus military and aviation-oriented memorabilia.

The growth of Charlotte/Douglas International Airport and the growth of the Charlotte Region are tied closely together. The airport links Charlotte with markets in the United States and around the world – an important factor in today’s global economy. According to a 1997 report by the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute, the airport contributes nearly four billion dollars in annual total economic impact to the Charlotte region, providing 71,392 jobs to workers who earn $1.968 billion in wages and salaries.22

Brief Architectural Description

Ryan L. Sumner

April 25, 2002

Location Description:

The W.P.A. / Douglas Airport Hangar is situated in the northeast corner of the Charlotte/Douglas International Airport property in southwest Mecklenburg County. The rear elevation of the structure faces northward and overlooks a steep slope down toward Airport Road and the Norfolk Southern Railroad (formerly Southern Railroad) line, which lies approximately one hundred meters behind the structure. The hangar lies one thousand meters south of Wilkinson Boulevard, the only four-lane highway in the Carolinas at the time of the airport’s construction.23 Charlotte Mayor Ben Douglas chose this site because of its proximity to the rail line, and Wilkinson Boulevard, since in 1936 pilots navigated largely by visual reference to ground landmarks.24

To the west of the hangar, the land is generally flat, grassy, and empty. None of the other structures that stood on the western side of the Hangar is extant. Immediately west of the hangar stood Charlotte Streetcar #85, which was moved to the airport following the close of the trolley line in 1938 and was converted into an office for the Air National Guard; it was removed in the 1940’s.25 Slightly farther west stood the seventy-five feet tall radio beacon tower. The airport’s administration / terminal building sat atop a now leveled slope a few yards east.

The hangar’s front visage faces south over a flat open asphalt apron (approximately twice the size of the hangar) and over the modern runways of Charlotte/ Douglas International Airport. The roar of airplanes taking off and landing in close proximity drown out conversations and fittingly dominate the space

The area east of the hangar is a continuation of the asphalted area that lies in front of the structure and is currently used as a parking lot. A non-extant runway lighting system stood on the east side of the hangar.

Structural Description:

The W.P.A. / Douglas Airport Hangar is a one story, one hundred feet wide by one hundred feet deep, by thirty feet tall, metal structure. It is typical of aviation hangars built by the Works Progress Administration (later known as the Works Projects Administration), which utilized stock plans and worked on 11 airport projects in North Carolina before 1940.26

The exterior structure has a gable roof with rounded cornices composed of prefabricated sheet metal with a pressed corrugated pattern. The exterior roof is covered with weatherproofing tar and painted silver.

The rear north-facing side of the hangar is largely composed of like materials and is punctuated by six bays of window groups. Each window group on the rear consists of a central section of fifteen panes arranged in three horizontal rows of five. On either side of each large section is a smaller group of nine panes arranged in three horizontal rows of three. The higher two-thirds of each small section are hinged at the top and can be pushed outward and propped open for ventilation. “CAROLINAS AVIATION MUSEUM” has been recently painted across the rear wall of the structure, but underneath this new sign, it is possible to read “DOUGLAS AIRPORT CHARLOTTE N.C.”

The front south-facing side is characterized by ten bays of doors that are approximately 22 feet high and ten feet across; each is punctuated with a window grouping of two sets of nine panes arranged three panes wide by three panes high. These ten doors constitute the central entrance and slide left or right along five tracks—closing the hangar completely, or creating a maximum opening of eighty feet. “CAROLINAS AVIATION MUSEUM” has recently been painted across the structure’s front above the door, and an Esso sign has been mounted near the roofline, just below a windsock mounted upon the roof.

The exterior of the hangar retains a very high level of integrity. The east and west walls have no windows and are composed of same material as the roof, but with a tighter corrugation pattern. A small addition to the west side and a larger addition to the east side were constructed sometime after the original construction. The small addition is approximately ten feet high, nine feet wide, and eighteen feet deep; it is composed of cinder blocks and wood, with a shed roof. The large addition on the west side is similarly composed of white cinder block with a shed roof, but is seventeen feet high, twenty feet wide, and one hundred twenty feet deep.

The interior of the hangar is completely open from floor to vaulted ceiling. The roof and walls are totally supported by a steel frame skeleton that consists of six I-beam tented arches, which transverse the structure from east to west. The floor is poured cement, and the interior walls are merely the reverse sides of the sheet metal used for the exterior walls.

Endnotes:

1. Charlotte Observer, (April 2, 1930), p1.; Charlotte Observer, (December 11, 1930); Blythe, LeGette and Charles Brockman, Hornet’s Nest: The Story of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County, (Charlotte, NC: Heritage Printers, 1961), p265-6

2. Carter, Gary, “Ben Douglas, Sr.: Charlotte’s Former Mayor Lives in a Future of His Own Creation,” Clippings Folder, Ben E. Douglas Papers, Robinson-Spangler Carolina Room, Public Library of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County.

3. Carter, Gary, “Ben Douglas, Sr.: Charlotte’s Former Mayor Lives in a Future of His Own Creation,” Clippings Folder, Ben E. Douglas Papers, Robinson-Spangler Carolina Room, Public Library of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County.

4. Carter, Gary, “Ben Douglas, Sr.: Charlotte’s Former Mayor Lives in a Future of His Own Creation,” Clippings Folder, Ben E. Douglas Papers, Robinson-Spangler Carolina Room, Public Library of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County.

5. Charlotte City Clerk, Minutes of the City Council (Special Meeting September 3, 1935).

6. Charlotte City Clerk, Minutes of the City Council (Nov. 13 1935).

7. Douglas, Ben E., “Ledbetter, L. L., City Treasurer to Ben E. Douglas,” (March 11, 1960), Ben E. Douglas Papers /Manuscript 109 , University of North Carolina, J. Murray Atkins Library Special Collections.

8. United States and Works Progress Administration North Carolina, North Carolina W.P.A.: Its Story (Information Service: 1940) .p1

9. Douglas Ben E., History of the Airport Scrapbooks, storage in the Robinson-SpanglerCarolina Room, Public Library of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County (labeled photographs)

10. Douglas, Ben E., History of the Airport Scrapbooks, storage in the Robinson-Spangler Carolina Room, Public Library of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County (undated unnamed newspaper clipping, circa Dec 1935)

11. Charlotte Observer (April 25, 1982)

12. Charlotte Observer (February 28, 1950)

13. Douglas Ben E., History of the Airport Scrapbooks, storage in the Robinson-Spangler Carolina Room, Public Library of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County.

14. Charlotte News (April 19, 1941).

15. Charlotte News (April 19, 1941); Charlotte Observer (February 28, 1950)

16. Charlotte City Directory (1941, 1942, 1943, 1944, 1945, 1946); Interview with Fred Wilson, President Carolinas Historic Aviation Museum (April 1, 2002)

17. Dedication Program (July 10, 1954), Douglas Airport, Clippings Folder, Robinson-Spangler Carolina Room, Public Library of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County.

18. Kratt, Mary and Mary Boyer, Remembering Charlotte: Postcards from a New South City, 1905—1950, (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2000) p128

19. Interview with Fred Wilson, President Carolinas Historic Aviation Museum (April 1, 2002)

20. Charlotte Observer (October 21, 1992)

21. Charlotte Observer (October 21, 1992)

22. Charlotte/Douglas International Airport, Official Website. Available at: http://www.charlotteairport.com/economic.htm

23. Douglas, Ben E., “Douglas Presents History to Library,” Clippings Folder, Ben E. Douglas Papers /Manuscript 109 , University of North Carolina Charlotte, J. Murray Atkins Library Special Collections.

24. Douglas, Ben E. “‘Dad’ Douglas is on Cloud 9,” Clippings Folder, Ben E. Douglas Papers /Manuscript 109 , University of North Carolina Charlotte, J. Murray Atkins Library Special Collections.

25. Morrill, Dan L., “A Brief History of Streetcars in Charlotte,” Charlotte Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission Website, available at: www.cmhpf.org/essays/streetcars.html

26. United States and Works Progress Administration North Carolina, North Carolina W.P.A.: Its Story (Information Service: 1940) p46.

1. Name and location of the property: The property known as the Yandell Hotel and Grocery Store is located at 331 Main Street, Pineville, North Carolina.

2. Name and address of the present owner of the property: The present owner of the property is:

W. A. Yandell Rental and Investment Co.

PO Box 386

Pineville, NC 28134

3. Representative photographs of the property: This report contains representative photographs of the property. Photographs are available at the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission office.

4. Maps depicting the location of the property: This report contains a map depicting the location of the property.

5. Current deed book reference to the property: The most recent deed to this property is recorded in Mecklenburg County Deed Book 02036 on page 293. The tax parcel number of the property is 22106102.

6. A brief historical sketch of the property: This report contains a brief historical sketch of the property.

7. A brief architectural description of the property: This report contains a brief architectural description of the property.

8. Documentation of why and in what ways the property meets criteria for designation set forth in N. C. G. S. 160A-400.5:

a. Special significance in terms of its history, architecture, and/or cultural importance: The Commission judges that the property known as the Yandell Hotel and Grocery Store does possess special significance in terms of Charlotte-Mecklenburg. The Commission bases its judgment on the following considerations:

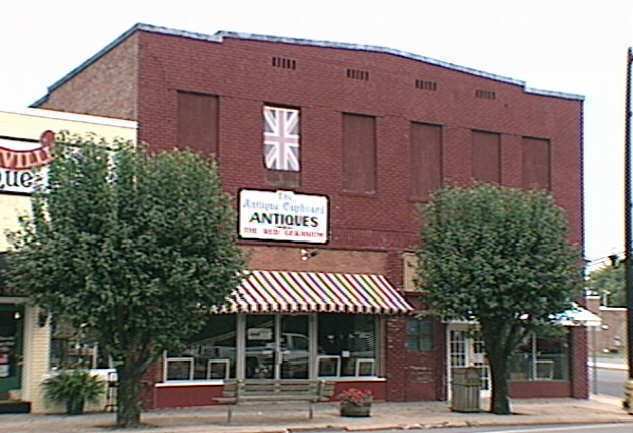

1) Built in 1925 by W.A. “Willie” Yandell, the Yandell Hotel and Grocery Store holds an important and prominent position in the Town of Pineville’s commercial core.

2) The building has a close association with W.A. “Willie” Yandell, a business man who was instrumental in the non-textile commercial development of the town of Pineville during the twentieth century, building and owning much of the town’s commercial core.

3) The Yandell Hotel and Grocery Store is closely associated with W.A. “Willie” Yandell. The businessman maintained an office, operated a hotel, and ran several other businesses in the building.

b. Integrity of design, setting, workmanship, materials, feeling and/or association: The Commission contends that the physical and architectural description which is included in this report demonstrates that the Yandell Hotel and Grocery Store meets this criterion.

9. Ad Valorem tax appraisal: The Commission is aware that designation would allow the owner to apply for an automatic deferral of 50% of the Ad Valorem taxes on all or any portion of the property which becomes a designated “historic landmark.” The current total appraised tax value of the land and improvements is $1,010,400. 331 Main Street occupies 9037 square feet of the 20,105 total square feet of improvements on the tax parcel.

10. Portion of property recommended for designation: The exterior of the building, the land on which it sits, and the sidewalk directly in front of the building are recommended for historic designation.

Date of preparation of this report: April 6, 2006

Prepared by: Stewart Gray and Hope Murphy

Historical Overview

Pineville

Pineville, North Carolina is located approximately eleven miles south of the city of Charlotte. The small town had its beginnings as a train stop when the Charlotte and South Carolina Railroad opened a depot in 1852. The town, incorporated in 1873, became a busy center for agricultural support and textiles in the next few decades.[1] In 1890 businessmen from Charlotte opened the Dover Yarn Mill in Pineville. By the time the Mill had added a weaving department in 1902 over two hundred people were employed at the Mill.

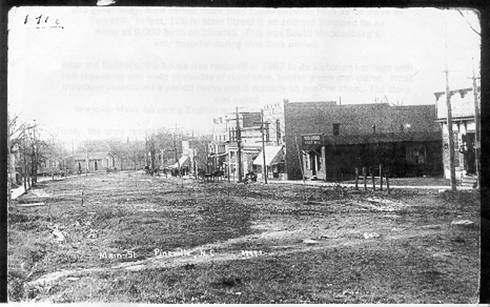

In 1903 the population of Pineville had reached 700, most of them involved in some way with the cotton industry. Those not employed by the mill labored as cotton farmers. Autumn would bring farmers to Main Street where they would form long lines in order to have their cotton ginned. Saturdays would also bring farmers to town shop, pay debts, or trade mules.[2]

For most of its history the south side of Main Street has been owned by the Yandell family. W.A. “Willie” Yandell began acquiring land on the south side of Main Street in 1919. In that year he purchased one half acre from C .H. Griffin and his wife Rana[3] During the next four years Yandell acquired additional Main Street frontage from the Wherry and Bailes families.[4] In a 1987 interview in the Charlotte Observer, Willeen Yandell, W. A.’s daughter, recounted that when her father arrived in Pineville in 1912, Main Street was only a wagon path. The elder Yandell, recognized that the growing town needed services like grocery stores and began to develop them. [5]

Main Street became more connected to the outside world beginning in 1927 when a bridge was built over the nearby Big Sugar Creek. With this bridge Main Street became part of the main route between Charlotte and Columbia, South Carolina. W. A. Yandell realized a boom in his burgeoning business when work crews arrived in Pineville to begin labor on the project. Yandell recounted to newspaper reporter Joe Flanders in the 1960s that he remembered the day shortly before Christmas of 1927 when the road contractor arrived in Pineville. The contractor had with him 50 teams of mules and enough men to run them. Faced with no place to house his men, never mind the mules, the contractor turned to Yandell. For the year that it took to build the bridge and attached road Yandell housed men at his hotel and found space to feed and keep the mules.[6]

In June 1929 the business owners along the street petitioned the Mayor of the town and Board of Alderman to “grade and pave” the street. The property owners, Mr. Yandell being the largest with 250 feet of frontage, agreed to pay one-quarter of the cost of the project.[7] Into the 1930s Main Street in Pineville remained only one of two paved streets in Pineville, the other being Polk Street.

By the 1930s Pineville housed along its two block business district: five general stores, a dime store, a drug store, a doctor’s office, hardware store, pool room, livery stable, blacksmith, post office, icehouse, movie theatre, and funeral home.[8] The south side of Main Street had a barbershop, a theater, and a post office. There was also a grocery store run by Yandell, over which there were hotel rooms. Yandell’s business office was next door. Joe Griffin recounts local residents “could get a loan, cash a check, pay rent, or seek legal advice” there[9] Such services would have been vital in the community that lost its only bank, Pineville Loan & Savings Company, in 1929 at the outset of the banking crisis that preceded the Depression.[10] Griffin recounts that as a young boy in Pineville, during the 1930s, most people who lived in or near Pineville, shopped on Main Street.[11] Trips to uptown Charlotte were rare and became more so during World War II when gas became rationed.[12] Griffin recounts that the sidewalk on either side of Main Street was about four feet wide. Trees and grass were planted between the sidewalk and the road. This grassy strip served as a place for the stores to display items on nice days.[13]

Main Street Pineville 1915