The Thomas T. Sandifer House

This report was written on June 15, 1996

2. Name and address of the present owner of the property: The owner of the property is:

Mrs. Nada Bradshaw

P.O. Box 1692

Belmont, North Carolina 28012

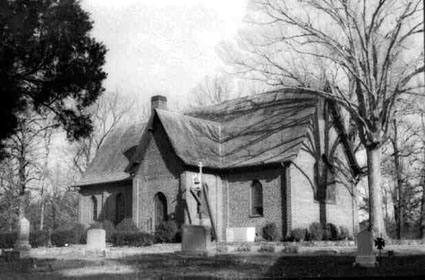

3. Representative photographs of the property: This report contains representative photographs of the property.

4. Maps depicting the location of the Property: This report contains a map which depicts the location of the property.

5. Current deed book references to the property: The Thomas T. Sandifer House is sited on Tax Parcel Numbers 053-161-05 and 053-161-07 and is listed in Mecklenburg County Deed Book 1236 at page 131.

6. A brief historical sketch of the property: This report contains a brief historical sketch of the property prepared by Frances Alexander.

7. A brief architectural description of the property: This report contains a brief architectural description of the property prepared by Frances Alexander.

8. Documentation of why and in what ways the property meets criteria for designation set forth in N.C.G.S. 160A-400.5:

a. Special significance in terms of history, architecture, and cultural importance: The Commission judges that the property known as the Thomas T. Sandifer House does possess special significance in terms of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County. The Commission bases its judgment on the following considerations: 1) the Thomas T. Sandifer House was built in the 1850’s and is one of the few ante-bellum houses remaining in this section of Mecklenburg County; 2) the Thomas T. Sandifer House is one of the few extant farmhouses located, and facing, the Catawba River, along which many of the important early farms in Mecklenburg County were sited; 3) the Thomas T. Sandifer House was constructed by Sandifer, a physician and farmer, whose dual occupations represent a common mid-nineteenth century economic pattern in Mecklenburg County; and 4) the Thomas T. Sandifer House was the home of Sandifer, who served as county commissioner and a representative to the state legislature.

b. Integrity of design, setting, workmanship, materials, feeling, and association: The Commission contends that the architectural description by Frances Alexander included in this report demonstrates that the Thomas T. Sandifer House property meets this criterion.

9. Ad Valorem Tax Appraisal: The Commission is aware that designation would allow the owner to apply for an automatic deferral of 50% of the Ad Valorem taxes on all or any portion of the property which becomes designated as a historic landmark. The current appraised tax value of the improvements to the Thomas T. Sandifer House is $78,180.00. The current appraised tax value of the 10.940 acres associated with the house is $59,500. The total appraised tax value of the property is $137,680.00. The land is zoned R-3.

Date of Preparation of this Report: June 15, 1996

Prepared by:Frances P. Alexander and Dr. Dan L. Morrill

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission

2100 Randolph Road

Charlotte, North Carolina 28207

Phone: (704) 376-9115

The Thomas T. Sandifer House is located on Moore’s Chapel Road in the Paw Creek Township of western Mecklenburg County. Paw Creek is roughly six miles west of the city center of Charlotte. Sited on 10.940 acres on the east side of Moore’s Chapel Road, the Sandifer property is located approximately 1/2 mile east of the Catawba River. Moore’s Chapel Road begins at Wilkinson Boulevard south of the property, and I-85 crosses Moore’s Chapel Road north of the Sandifer property. The Sandifer House is sited on a slight knoll, and a deep lawn separates the house from the road. The lawn contains mature trees and plantings, although there have been some losses in recent storms. To the rear of the house, the site descends sharply to a creek, called Catawba Tributary, where the property becomes wooded. The Catawba Tributary follows the modern rear property line. The only other structure on the site is a modern garage. The proposed designation includes the Thomas T. Sandifer house and the 10.940 acre farm site, but excludes the modern garage.

The Thomas T. Sandifer House is a two story, single pile, frame building with a one story, rear lean-to. The house has weatherboard siding; a brick foundation, which replaced a stone pier foundation; and a hip roof covered in asphalt shingles. The roof has wide, overhanging eaves. An enclosed, one story, rear porch extends across the rear lean-to. A centrally placed dormer tops the lean-to, and is flanked by two exterior, brick chimneys. The chimneys are modern replacements but occupy the same position as the originals. A small one story addition with gable roof is now situated at the rear of the north elevation.

The house has a symmetrical, three bay facade covered by a one story, hip-roofed porch. The porch is supported by paired, classical, box piers with stylized capitals. The porch piers rest on brick pedestals, added in the early to mid-twentieth century. A replacement balustrade has been added between the brick pedestals. The central entrance has a single, paneled wood and glass door with sidelights and transom. The door is a mid-twentieth century replacement. The molded door and window surrounds have stylized scrolled brackets across the lintels. The windows are six-over-six light, double hung, wooden sash. The corners of the house are delineated by stylized pilasters, and there is a wide, flat cornice under the broad eaves. The interior has a narrow, central hall which now opens into the modern rear porch. This rear doorway is original with molded surrounds, sidelights, and transom.

The hall has plaster walls; molded chair railing, baseboards, and door surrounds; and plaster walls. However, the floors are now carpeted, and the ceiling is stuccoed. Located along the south wall of the hall the staircase rises to a landing. Although the risers are now covered in carpet, the staircase is original with a classical, box pier newel and simple, square balusters. The hall doors appear to be early to mid-twentieth century paneled replacements. The south side of the main block is occupied by a parlor. The parlor has original molded baseboards, chair railing, and cornice. The parlor has a delicate, classical fireplace which is also original. Alterations include the addition of carpeting and a replacement tile ceiling. A paneled door leads to the dining room which is situated on the south side of the lean-to.

As in the parlor, the dining room is now carpeted, but original features include a bold, vernacular classical mantel and a built-in china cupboard with glass and wood doors. The molded baseboards, chair railing, and door surrounds, and plaster walls are also original. Replacement tiles cover the original ceiling. On the north side of the main house was a second parlor, which is now used as a bedroom. This room has original plaster walls and molded surrounds. However, the simple brick fireplace mantel with corbeled shelf, is an early twentieth century addition. Flanking the fireplace are two doors. On the north side, the paneled door leads to a closet while the south door opening has been converted to a book shelf. This room is also carpeted and has a replacement ceiling. An entrance has been cut from this room to the north addition, which houses a bathroom. To the rear of the north parlor is the kitchen. There are few, if any, original features to the kitchen. Its does appear to date to the early to mid-twentieth century, and the replacement stucco ceiling appears to be post-World War Two. A window on the rear (east) elevation has been removed and opens directly into the enclosed porch. The rear porch has been enclosed within the past twenty years. This room has tall banks of windows, two skylights, and a bold, vernacular Victorian mantel which is not original to the house.

The upstairs has two bedrooms which open from a short hall. A small room is located between the two large bedrooms. The north bedroom has hardwood floors, plaster walls, and molded door and window surrounds. A fireplace along the east wall has a simple, vernacular classical mantel. A door next to the fireplace leads to a bathroom which occupies the rear dormer. The south bedroom also has hardwood floors (now carpeted), plaster walls, molded surrounds, and a matching vernacular classical mantel. In the past 30 years, a closet has been built by partitioning one corner of the room. The small intermediate room has carpeted hardwood floors and plaster walls, but no fireplace. A modern, one car garage with front gable roof is sited southeast of the house. The garage is excluded from the proposed designation.

The Thomas T. Sandifer House has undergone modification. In the 1940s, brick pedestals and a new balustrade were added to the porch; and paneled replacement doors were added on the interior. Since 1950, the original stone foundation was covered and infilled with brick. The house was originally built over tree stumps which added support, but these were removed by the owners after 1950. Other exterior changes have included the enclosure of a rear porch and the bathroom addition to the north elevation. Interior changes since World War Two have included the remodeling of the upstairs bathroom and the kitchen and the addition of carpeting and replacement ceiling tiles. A rock-lined well was also covered in the 1950s. Despite these modifications, the Sandifer House retains its distinctive I-house form and floor plan. Much of the historic fabric is intact, including original siding and exterior detailing.

The Thomas T. Sandifer House and its now 10.940 acres were once part of a larger 246 acre tract purchased by Dr. Thomas T. Sandifer in the 1850s. Sandifer bought the property, which then included Catawba River frontage, from the heirs of Isaac A. Wilson (Wilson Deeds 1864, 1869). Wilson had died in 1853 in California, probably having migrated west because of the gold rush. Isaac Wilson had inherited the farmstead from his father, Robert Wilson, who had bought the land when it was known as the Smartt farm. The original 246 acres was bounded by the Catawba River and properties owned by John and William Clanton, William Beaty, R.J. Wilson, and the McLeary family (Martha Wilson Deed 1856).

The extant house was apparently built by Sandifer. At his purchase, Sandifer enacted deeds with each of Isaac Wilson’s five heirs, and two of the deeds specify amounts of $200.00 and $300.00, neither amount sufficient to cover the value of the house. Sandifer also seems to have traded property with one of the heirs, Martha A. Wilson. Sandifer sold, or granted, her property he owned on Tuckaseegee Road in October 1856, several months after purchasing her portion of the Wilson farm (Grantor Index 1840-1918; Wilson Deed 1856). A physician, Thomas Sandifer held a considerable estate in 1860. In addition to this farm tract valued at $2,500.00, Sandifer also owned other property in the Paw Creek Township (Grantor Index 1840-1918). His personal estate was worth $7,000.00, and he held three slaves. Sandifer’s slaves included two men, ages 33 and 20, and one woman age 31. (The former location of the single slave house is not known.) At the same time, a carpenter, W.B. Bradford, was boarding with the Sandifer family, and Bradford may have been working on the house (U.S. Census 1860 ).

Born on October 20, 1818, Thomas Sandifer was a native South Carolinian, and it is not known when he migrated to Mecklenburg County. His two marriages produced 11 children. His first wife, by whom he had four children, was Ann Wilson of the Steele Creek community of Mecklenburg County. After her death in 1864, Sandifer married a younger woman, Elizabeth G., and they had seven children (Gatza 1989). Throughout the 1870s and 1880s, Sandifer continued his medical practice and farming (Branson Business Directory 1877; City Directory of Charlotte Gazeteer 1884, 248). He died in 1901 and was buried in Paw Creek Presbyterian Church cemetery. By the 1850s, when Sandifer purchased this riverfront farm, the population of the county seat of Charlotte had slowly doubled since the American Revolution to 1,065 while Mecklenburg County had 18,750 residents (Tompkins 1903, 123). Despite the richness of the farmland and the gold mining of the region, population growth had been stymied by poor transportation and the great distances to the ports of Wilmington and Charleston.

Although a small town in the ante-bellum period, Charlotte nonetheless became important in the back country of the Carolinas because of these natural assets (Hanchett 1993, 55). The coming of the Charlotte and South Carolina Railroad in 1852 ended the transportation dilemma, offering the fertile land of Mecklenburg County access to the port of Charleston. Two years later, in 1854, the North Carolina Railroad reached Charlotte, connecting the back country with the North Carolina coastal plain. By 1861, four railroads converged on Charlotte, and the town quickly became a cotton marketing center in the Piedmont. With the greater potential for shipping farm products, the population doubled to 2,265 between 1850 and 1860 (Hanchett 1993, 65). As early as 1802, Mecklenburg County had become a center for the production of short staple cotton with more cotton gins than any other North Carolina county. Although located outside the traditional plantation regions of the North Carolina coastal plain and the South Carolina low county, Mecklenburg County was the third largest cotton producing county in the state in 1850 (Hanchett 1993, 47).

However, unlike the coastal regions of the Carolinas, cotton cultivation in the Piedmont back country did not produce the highly stratified plantation economy of the Deep South. The high cost of transportation made Mecklenburg County agriculture more diversified, with less reliance on cash crops such as cotton. Difficulties in shipping also encouraged the establishment of numerous flour milling and still operations. In 1850, 1,692 people were engaged in agriculture; 234 in manufacturing and trade, 49 in commerce, 94 in mining, and 58 in professional occupations (Tompkins 1903, 123). Mecklenburg farmers grew wheat and corn as well as cotton, and in 1850 had one of the most productive and diverse farm economies in the North Carolina, cultivating every crop except tobacco (Alexander 1908, 174).

The importance of cotton as a cash crop encouraged slavery. Only 14% of the population in 1790, black slaves comprised 40% of the population by 1850 although only 70 men owned 20 or more slaves on the eve of the Civil War. For Mecklenburg County, this constituted a planter class, although one which did not hold vast estates with large numbers of slaves. Indeed, few Mecklenburg residents made purely agricultural fortunes. Only one planter in 1850 owned 50 slaves, and only one plantation covered more than 1,000 acres (Hanchett 1993, 50). The more typical planter had diversified interests, usually combining the operation of a store in town, a law or medical practice, or other non-agricultural pursuits as Dr. Sandifer did. Although the county had few planters, it supported a number of moderately wealthy farmers, who owned approximately 10 slaves. In 1860, 160 men held 10 to 19 bondsmen, while 650 owned one to nine slaves (Hanchett 1993, 51). Sandifer exemplified this latter group of successful farmers with his limited number of slaves. One-third of the county population owned no slaves, and either owned a few acres of land or had no landholdings at all. Planters, professionals, and prosperous merchants made up less than 1% of ante-bellum Mecklenburg; farmers and small merchants who owned a handful of slaves and 50 or more acres of land comprised 20 to 25% of the population; non-slaveholding residents constituted 35%; and black slaves, and the small number of freedmen, formed 40% of the Mecklenburg County population (Hanchett 1993, 53).

Remarkably, Charlotte sustained little damage during the Civil War, and perhaps most importantly, its rail lines to the seaports were left intact. The cotton trade rebounded quickly, and the county shipped the same amount of cotton in 1866 as it had in 1860. Wartime scarcities and transportation problems drove prices up, and Charlotte, in contrast to much of the South during Reconstruction, entered a boom period, doubling its population between 1860 and 1870 (Hanchett 1993, 69). Mecklenburg farmers, such as Sandifer, who had not relied heavily on slave labor and cash crop cultivation, were able to continue farming with little disruption and with the hopes of high prices. During the 1870s, as Charlotte prospered, new rail lines were constructed to further ensure adequate transportation for goods. In 1872, the Carolina Central was built providing a direct connection, through Charlotte, from Lincolnton to Wilmington. With the construction of the Atlanta and Charlotte Air Line, linking Richmond and Atlanta via Charlotte, the city became an important regional trading center with the convergence of six rail lines (Hanchett 1993, 72). The purchase of a cotton press by the town made Charlotte the center of the upcountry cotton market and set the stage for the development of textile production in the 1880s and 1890s. During this period, Dr. Sandifer served as a member of the Mecklenburg County Board of Commissioners, elected in 1878, and as a representative to the North Carolina General Assembly, beginning in 1883 (Blythe 1961, 453, 462). In addition, Sandifer continued his medical practice into, at least, the mid-1880s when he was in his late 60s.

From land transaction records in the 1880s and 1890s, it is clear that Sandifer continued to own considerable land in Paw Creek Township, in addition to his 246 acre home place (Grantor Index 1840-1918). Sandifer died in 1901, and his will apparently caused disputes among family members over the division of the land. In 1904, his widow, Elizabeth, sued the eighteen surviving family members. The division of land in the settlement confirms that the original 246 acre farmstead was virtually intact in 1904 although Mrs. Sandifer had sold some land along the Catawba in 1904. Elizabeth Sandifer retained 89 acres, which included river frontage and probably the house, while the eighteen children and grandchildren shared 149 acres. The commission established to settle the dispute directed the children to sell their collective inheritance (Mecklenburg County Deed Records, Book 195, Page 395).

Thus after Sandifer’s death, the original farmstead was subdivided. Mrs. Sandifer continued to own a large portion of the original Sandifer farmstead until at least World War I. In 1911, she sold parcels to the Piedmont Traction Company, the predecessor company to the Piedmont and Northern Railway. Piedmont Traction had been organized in 1910 to construct an interurban rail line between Charlotte and Gastonia, connecting the street railway systems of these two rapidly developing textile hubs. Similarly, in 1912, Mrs. Sandifer sold a parcel to the Southern Power Company, now Duke Power Company, as the company began providing electric power to the textile mills. The Sandifer farm, located on the west side of the county, laid in the path of development for the burgeoning textile industry (Grantor Index 1840-1918). Elizabeth G. Sandifer died sometime after 1912, and it seems probable that at her death John William Grice bought the property. After Grice’s death in the early 1940s, his grandson, Robert L. Auten, bought a 21 acre tract, which included the house, from the other 50 Grice heirs (Mecklenburg County Deed, Book 1121, Page 18, 1944). According to the current owner, Robert Auten spent part of his childhood in the Sandifer house so it seems likely that J. W. Grice bought the property after Mrs. Sandifer’s death (Bradshaw Interview 1994). Robert Auten, a contractor, made many of the alterations to the house. In 1947, Bob Auten sold the house and 14 acres to his brother and sister-in-law, Frank and Gladys Auten. Frank and Gladys Auten, in turn, sold the property to the current owner, Nada Bradshaw, and her husband, Nelson Bradshaw, both natives of Belmont, in 1950 (Bradshaw interviews 1994, 1996).

The Thomas T. Sandifer House is one of the few remaining ante-bellum farmhouses in Mecklenburg County. Facing the Catawba River, the Sandifer house and farm originally fronted on this river, along which many of the earliest and most prosperous farms in the county were located. The house and its surrounding 10.940 acres is the last vestige of the once 246 acre farm owned by local physician and farmer, Thomas T. Sandifer. Sandifer exemplifies the class of moderately wealthy ante-bellum farmers in Mecklenburg County, who combined professional or commercial pursuits with a diversified form of farming. This middling economic group characterized agricultural life in the back country, in contrast to the highly stratified plantation economy of coastal regions. The survival of this western Mecklenburg County ante-bellum farmstead is particularly remarkable because this area of the county laid in the center of the textile and transportation corridor between Charlotte and Gaston County which developed in the early twentieth century.

Alexander, J. B. Reminiscences of the Past Sixty Years. Charlotte: Ray Printing Company, 1908.

Blythe, LeGette and Charles R. Brockmann. Hornet’s Nest. Charlotte: McNally of Charlotte, 1961.

Branson, L., ed. The North Carolina Business Directory. Raleigh: Branson and Jones, 1872.

Branson’s Business Directory. Raleigh: Branson and Jones, 1877.

Charlotte City Directory, 1879-1880.

City Directory of Charlotte and Gazetteer for 1884-1885. Atlanta: Interstate Directory Cornpany, 1884.

Gatza, Mary Beth. Research Materials on the Thomas Thorn Sandifer House. Records of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission, 1989.

Hanchett, Thomas W. Sorting Out the New South City: Charlotte and Its Neighborhoods. Ph.D. dissertation. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Department of History. 1993.

Interview with Nada Bradshaw, owner. October 1993, June 1994, and May 1996.

Mecklenburg County Deeds. Grantor and Grantee Indices. 1840-1918.

Mecklenburg County Deeds. Martha A. Wilson to T. T. Sandifer. Deed Book 4, page 694. 12 May 1856.

Mecklenburg County Deeds. R. L. and Leona Auten to Frank and Gladys Auten. Deed Book 1236, page 131. 12 February 1947.

Mecklenburg County Deeds. R. L. Grice to R. L. Auten. Deed Book 1121, page 18. 22 June 1944.

Mecklenburg County Deeds. E. G. Sandifer to Piedmont Tract Company. 6 March 1911.

Mecklenburg County Deeds. E. G. Sandifer to Southern Power Company. I October 1912. Mecklenburg County Deeds. T. T. Sandifer Estate to E. G. Sandifer et al. Deed Book 195, page 395. 7 April 1905.

Mecklenburg County Deeds. R-L. Wilson to T. T. Sandifer. Deed Book 5, page 41. 26 April 1864.

Mecklenburg County Deeds. Sarah and William Fite to T. T. Sandifer. Deed Book 4, page 729. 10 April 1857.

Mecklenburg County Deeds. S. C. Wilson to T. T. Sandifer. Deed Book 6, page 426. 20 September 1856.

Strong, C. M. History of Mecklenburg County Medicine. Charlotte: Charlotte News Printing House, 1929.

T’hompson,Edgar. Agricultural Mecklenburg and Industrial Charlotte. Charlotte: Chamber of Commerce, 1926.

Tompkins, Daniel A. History of Mecklenburg County and the City of Charlotte, 1740-1903. Charlotte: Observer Printing House, 1903.

U.S. Bureau of Census. Population Schedules, 1860, 1870, 1880.