This report was written on October 3, 1979

1. Name and location of the property: The property known as Morrocroft is located at 2525 Richardson Drive in Charlotte, NC.

2. Name, address, and telephone number of the present owner and occupant of the property:

The present owner of the property is:

James J. Harris & Angelia M. Hazels

Box 220427

Charlotte, NC 28222

Telephone: (704) 366-0925

3. Representative photographs of the property: Representative photographs of the property are included in this report.

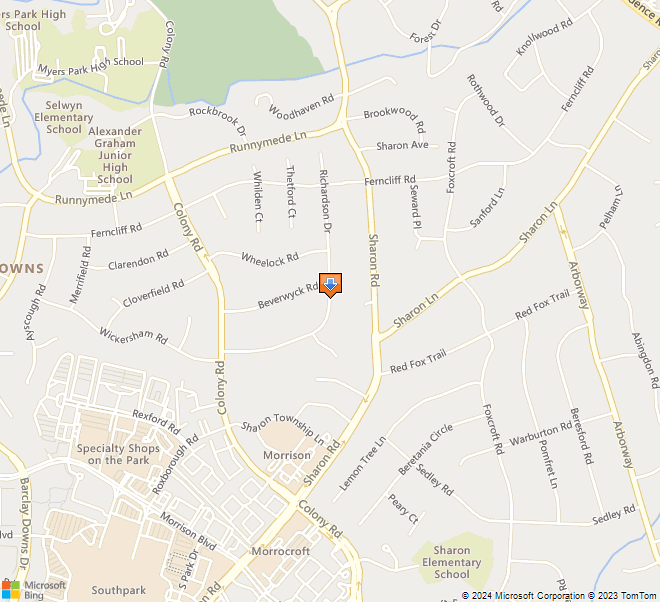

4. A map depicting the location of the property: This report contains a map which depicts the location of the property.

5. Current Deed Book Reference to the property: The most recent reference to this property is recorded in Mecklenburg County Will Book 7, page 552. The Tax Parcel Number of the property is 177-078-04.

6. A brief historical sketch of the property:

Morrocroft was completed in 1927 as the home of Governor Cameron Morrison (1869-1953) and his second wife, Sara Eckerd Watts Morrson.1 A native of Richmond County, North Carolina, Morrison was an adroit and flamboyant politician. His initial forays into the public arena occurred in the 1890’s, when as a young attorney he headed the Red Shirt movement in Richmond County, a collection of citizens dedicated to the principles of white supremacy as a prerequisite for the progressive development of North Carolina. The only elective office which Morrison held during these years was as Mayor of Rockingham, NC, in 1893.2

Morrison moved his law practice to Charlotte, NC, in 1905. The Charlotte Observer described him as a young man of ability who possessed a clear, musical voice. On December 6, 1905, Morrison married Lottie May Tomlinson of Durham, NC, who was to be the mother of an only child, Aphelia Lawrence Morrison. Mrs. Morrison died in Presbyterian Hospital on November 12, 1919. A graduate of the Women’s College of Baltimore, MD, and Peace Institute in Raleigh, NC, Mrs. Morrison had been active in local civic affairs. During World War I, she had served as captain of a Red Cross canteen team at Camp Greene, a large military training facility in Charlotte.4 In 1920, Morrison opposed O. Max Gardner, Lieutenant Governor of North Carolina, in the Democratic primary for Governor. A principal ally of Morrison’s in this campaign was Senator Furnifold Simmons. Morrison was victorious, and in January, 1921, he became the Governor of North Carolina.5 In an address which he delivered on January 28, 1921, Governor Morrison emanated the progressive and assertive spirit which was to characterize his administration:

“We do not want to move and have our being as a crippled, weak and halting State, but we want to stand up like a mighty giant of progress and go forward in the upbuilding of our State and the glorification of our God.”6

It was customary for the chief executives of North Carolina to make bold promises at the outset of their terms, but Cameron Morrison did a better than average job in fulfilling his pledge to the people. He is remembered best as the “Good Roads Governor.” To bring North Carolina “out of the mud,” Morrison secured funds for a massive road building program. His objective was to construct paved highways to every county seat in the state. Governor Morrison also labored to upgrade the educational system throughout North Carolina. Allocations to the public institutions of higher learning were increased substantially during his administration. For example, fourteen buildings were erected on the campus of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill between 1921 and 1925, the years during which he served as Governor. Moreover, Morrison committed financial resources to the establishment of excellent primary and secondary schools at the local level. Another of Morrison’s major accomplishments was the improvement of medical facilities, especially those involved in the treatment of the mentally and emotionally infirm.7

That Governor Morrison placed education high on a list of priorities is not surprising. It is reasonable to infer that two considerations prompted him to do so. First, as a child in Richmond County, he had experienced the consequence of an inadequate public school system. Indeed, the school at Rockingham was open for only two months each year. Consequently, Morrison was compelled to obtain instruction from private teachers, from M. C. McCaskill at Orbs Springs, NC, and from William Carroll at Rockingham. Moreover, financial considerations prevented his matriculation at the University of North Carolina. He received his legal training in the office of Robert P. Dick in Greensboro, NC. Second, Morrison regarded himself as a student and admirer of Thomas Jefferson. “Democracy rests upon the principle of exact and equal justice to all, and regardless of class or station in life,” he proclaimed in a speech in New York City in 1924.9

In keeping with his Jeffersonian proclivities, Morrison believed that the existence of an educated citizenry was indispensable to the survival of the American republic. Indeed, he believed that those black citizens who could demonstrate their ability to grasp and appreciate public issues should be permitted to exercise the full rights of citizenship. Illustrative of Governor Morrison’s position on this matter was the fact that he channeled substantial resources to the improvement of the black colleges of North Carolina.10 Also noteworthy is the fact that the poll tax was unpolled during his administration.11 Governor Morrison’s personal life changed abruptly on April 2, 1924, when he journeyed to Durham, NC, and married Sara Eckerd Watts, millionairess and widow of George W. Regatta. A native of Syracuse, N.Y., and a trained nurse, she had married Watts, a noted financier and philanthropist, on October 25, 1917.12 Following the termination of Morrison’s tenure as Governor, the Morrisons moved to Charlotte and undertook the establishment of Morrocroft, an elegant residence and experiment farm of approximately three thousand acres just outside of the city. Completed in 1927, the house and attendant outbuildings were designed by Harrie Thomas Lindeberg, a prominent New York architect who specialized in the delineation of baronial country houses. Governor Morrison became known locally as the “Esquire of Morrocroft.”l4

Consistent with the New South philosophy which undergirded his system of values, Morrison labored to make his estate a model farm which would reflect the most advanced principles of scientific agriculture and thereby encourage the farmers of North Carolina to do likewise. He raised chickens, turkeys, hogs, and established one of the finest herds of Jersey cattle in the United States. Morrocroft also possessed large fields of grain, vegetables, and fruits.l5 The significance of his agricultural pursuits notwithstanding, Morrison continued to participate actively in the affairs of the Democratic Party. On December 13, 1930, Governor O. Max Gardner surprised many political pundits by appointing Morrison to the United States Senate to serve out the term of Senator Lee S. Overman, who had recently died.16 In 1932, however, Morrison was unsuccessful in his campaign against Robert R. Reynolds, an Asheville attorney.17 Reynolds used his opponent’s wealth as an effective political and oratorical weapon, accusing Governor Morrison of eating caviar and using a gold spittoon.18 In 1942, the voters of the Tenth Congressional District elected Morrison to the House of Representatives. He did not run for reelection. Instead, he campaigned in 1944 to return to the United States Senate. Again, he was unsuccessful, this time losing to Clyde R. Hoey of Shelby, NC.19 Governor Morrison did not run for public office again. His involvement in politics did not abate, however. He headed the North Carolina delegation to the National Convention of the Democratic Party in Chicago in 1952. His speech urging the delegates to preserve party unity appeared on national television.20 That Governor Morrison practiced what he preached was affirmed by the fact that he supported enthusiastically the candidacy of Adlai Stevenson for the Presidency. Indeed, the last political speech of his career, presented in Freedom Park in Charlotte, echoed his devotion to the Democratic Party which he had advocated as a young attorney in Richmond County in the 1890’s.

“Of course there have been actions taken by Democratic Administrations of which I have not wholly approved. Of course, there have been, and still are, individuals within the Democratic Party whom I would much rather have seen elsewhere. But we must never let anything swerve us from the only honorable course, and that is the true loyalty to the Democratic Party, now, as in the past, and forever.”2l

Governor Cameron Morrison died on August 21, 1953, of a heart attack at the age of eighty-three. His death occurred in Quebec, Canada, while on a trip with his grandson, James J. Harris, Jr. Mrs. Morrison predeceased her husband, having expired in 1950.22 Mrs. Morrison was a talented and exceptional human being. She was a member of Second Presbyterian Church.23 “Mrs. Morrison fights the devil through the Presbyterian church, and I try to give him a few good licks through the Democratic Party,” Governor Morrison once remarked.24 Mrs. Morrison served on the Board of the Charlotte YWCA and the Stonewall Jackson Training School. Moreover, she was generous in her support of Queens College in Charlotte, where Morrison Hall was named in her honor.25 Mrs. Morrison bequeathed Morrocroft to her step-daughter, Angelia Lawrence Morrison Harris, and to her step-daughter’s husband, James J. Harris.26 Mr. Harris, an insurance executive, was born in Athens, GA, on May 13, 1907. He and Mrs. Harris were married on October 6, 1934. Over the years, Mr. and Mr. Harris have disposed of the majority of Morrocroft Estate. The house now constitutes the centerpiece of a tract of 16.5 acres.27

NOTES

1 The Charlotte News (September 14, 1979), p. 3C. The Charlotte Observer (April 3, 1924), p. 1.

2 Beth G. Crabtree, North Carolina Governors 1885-1968 (State Department of Archive and History, Raleigh, 2nd printing rev.) pp. 120-121. Hereafter cited as Crabtree. The Charlotte Observer (March 3, 1920), p. 13.

3 The Charlotte Observer (February 27, 1905), p. 5.

4 The Charlotte Observer (November 13, 1919), p. 2.

5 Cameron Morrison, An address delivered by the Honorable Frank P. Graham to a Joint Session of the North Carolina General Assembly, March 31, 1955. Hereafter cited as Graham.

6 William H. Richardson & D. L. Corbitt, comp. & ed., Public Papers And Letters Of Cameron Morrison. Governor of North Carolina. l92l-1925 (Edwards & Broughton Co., Raleigh, 1927), pp. 17-18.

7 Crabtree. Graham. William S. Powell, North Carolina: A Bicentennial History (W. W. Norton & Co., New York, for the American Association of State and Local History, 1977), p. 184, 193, 196.

8 Graham. The Charlotte Observer (March 3, 1920), p. 13.

9 Graham. “Morrison, Cameron Family,” a folder in the vertica1 files of the Carolina Room of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Public Library. Hereafter cited as Family.

10 Crabtree.

11 Graham.

12 The Charlotte Observer (April 3, 1924), p. 1.

13 “Morrocroft, An Architectural Description” (August 18, 1979) by Carolina Mesrobian for the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Properties Commission.

14 Family.

15 Graham.

16 Family.

17 The Charlotte News (August 21, 1953), p. 10A.

18 Orison, Cameron. Old Clippings, a folder in the vertical files of the Carolina Room of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg-Public Library.

19 The Charlotte Observer (August 21, 1953), p. 1.

20 The Charlotte News (August 21, 1953), p. ICE.

21 Ibid.

22 The Charlotte Observer (August 21, 1953), p. 1.

23 Family.

24 Ibid. Governor Morrison characterized his own career in the following manner: “The Lord has just used a knotty-headed old Scotchman who uses his fists, instead of the standard kind of statesman.” The Charlotte News (August 21, 1953), p. 10b.

25 Ibid.

26 Mecklenburg County Will Book 7, page 552. 27. History of North Carolina, Volume III, Family and Personal History (Lewis Historical Publishing Co., Inc.)

7. A brief architectural description of the property: This report contains an architectural description of the property prepared by Carolina Mesrobian, architectural historian.

8. Documentation of way and in what ways the em Perth meets the criteria set forth in N. C. G. S. 160A-399.4:

a. Special significance in terms of its history, architecture, and/or cultural importance: Special historic significance in terms of Charlotte-Mecklenburg and North Carolina. The Commission bases its judgment on the following considerations 1) Morrocroft was the home of Cameron Morrison, Governor of North Carolina from 1921 until 1925, 2) the house and attendant outbuildings were designed by Harris Thomas Lindeberg, and 3) the house formed the centerpiece of an experimental farm.

b. Integrity of design, setting, workmanship, materials. feeling and/or association: The Commission judges that the architectural description included herein demonstrated that the property known as Morrocroft meets this criterion.

9. Ad Valorem Tax Appraisal: The Commission is aware that designation would allow the owner to apply annually for an automatic deferral of 50% of the Ad Valorem taxes on all or any portion of the property which becomes “historic property.” The current tax appraisal on the 16.5 acres of land is $330,000. The current tax appraisal on the improvements is $311,030. The most recent tax bill on the property was $10,737.25.

Bibliography

The Charlotte News.

The Charlotte Observer.

Beth G. Crabtree, North Carolina Governors 1585-1968 (State Department of Archives and History, Raleigh.

Frank P. Graham, “Cameron Morrison, An Address by the Honorable Frank P. Graham.” “Morrison, Cameron Family,” a folder in the vertical files of the Carolina Room of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Public Library.

“Morrison Cameron: Old Clippings” a folder in the vertical files of the Carolina Room of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Public library.

William S. Powell, North Carolina. A Bicentennial History (W. W. Norton & Co., New York, for The American Association of State and Local History, 1977).

Records of the Mecklenburg County Clerk of Superior Court.

Records of the Mecklenburg County Register of Deeds Office.

Records of the Mecklenburg County Tax Office.

William H. Richardson & D. B. Corbett, comp. & ed., Public Papers And Letters of Cameron Morrison, Governor of North Carolina, 1921-1925 Edwards & Broughton Co., Raleigh, 1927).

Date of preparation of this report: October 3, 1979

Prepared by: Dr. Dan L. Morrill, Director

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Properties Commission

139 Middleton Dr.

Charlotte, NC 28207

Telephone: (704) 332-2726

Architectural Description

Morrocroft was designed by the New York architect Harrie Thomas Lindeberg (1881? – 1959) for former North Carolina governor Cameron Morrison (served 1921 – 1925) in 1927. Lindeberg, who published a book on his domestic architecture in 1940, designed a number of baronial country houses in the United States for such clients as the Doubleday, Pillsbury, Dupont and Vanderbilt families. Clients in North Carolina included Martin L. Cannon of Charlotte, Mrs. L. J. Morehead of Salem, the Asheville Country Club, and several residents of Biltmore Forest.1

Lindeberg’s prevalent modes of domestic architecture were the Colonial and Tudor country manor house styles. Morrocroft (a combination of the family surname Morrison and the Scottish word for house)2 was built in the Tudor style. The asymmetry, picturesque massing, rhythmic spacing of mullioned, multi-paned grouped windows, and numerous multi-stack chimneys rising from steeply pitched gable roofs are tangible manifestations of the credo on domestic architecture compiled by Lindeberg and his senior partner, Lewis Colt Albro, in 1912.3 Harmony between house and environment was also of the utmost importance to Lindeberg’s total concept of design for Morrocroft, set on the rise of a gradually sloping tract of land, at one time surveyed at 3000 acres of farmland. Portions of the estate were developed from the 1950’s on for residential communities, Cotswold , Sharon Road, and Southpark Shopping Centers and an industrial park on Fairview Road. Although the house is surrounded at present by approximately 15 acres, much of the carefully planned landscaping is still intact.

The present grounds contain the main house and service court, garage, a brick garden house to the south of the house, the brick floor of a summerhouse located to the northwest of the house and a large frame grounds facility. According to the resident caretaker, Mr. Harkey, the latter building was moved to its present site northwest of the house in the early 1970s. The entrance to the grounds from Richardson Drive is bounded by brick walls carrying large decorative lead turkeys with full spread tails. These birds originally faced Sharon Road and were moved as civilization encroached on the estate. The drive, as illustrated in a 1927 house and partial grounds plan, divides into two paths, one leading to a walled service court attached to the right side of the house and a free standing garage standing to the north of the main complex; the other terminating in an oval drive in front of the main entrance, the front being oriented to the northeast.

Landscaping consists of a large number of English boxwood of several sizes and varieties. Small boxwood line the drives and a garden wall extending from the right side of the house, while the front of the house is lined with formal massings of large boxwood. A flagstone terrace leads from the southeast facade to a boxwood and brick lined lawn which terminates in a shallow-basined fountain with four spouts. What appears to have been a rose garden with brick paths radiating from a central nucleus lies due south of the house. The terraced rear (southwest) looks over a vast expanse of lawn to Sharon Road. Symmetrical, curved boxwood hedges line the grassy path and steps leading to the terrace and the main entrance of this facade. A shallow-basined pool with one spout formally defines each side of the lower entrance path. The northwest side of the house faces a dogwood forest. A wide variety of veteran trees shade the house and gardens. Trees include the magnolia, yellow poplar, American holly, ginkgo, Carolina hickory, black locust, white ash, flowering fruits and white willow and live oak.

Exterior, The Manor House (excluding the Service Court)

Morrocroft is characterized by a main two story block (two and-one half stories on the rear facade) with rambling one and one half story side wings which extend either parallel or at a right angle to the main block. Breaks in the wall surfaces which create solids and voids, diverse roof lines and projections from the central block such as the front entrance bay, an oriel window, and a one story office complete with its own roof and chimney provide asymmetrical and picturesque qualities. The house is comprised of narrow ochre and earth colored bricks said to have been made in Holland.5 Bondwork is a random, running type, stretchers being the more prevalent, with occasional headers. The steep, gable roofs which provide a vertical accent to the house have terracotta shingles. Heavy metal gutters with ornamental down spout clasps surround the house. The sprawling, horizontal massing of Morrocroft is further balanced by seven brick chimneys, six of which define the end walls of the wings, the seventh being centrally located in the main wing. The majority of the chimneys has three octagonal brick stacks with corbeled caps. Two chimneys on the service yard side have three clay pot stacks. Fenestration, while diverse in size and placement, is made homogeneous by the use of subtlety-tinted English leaded glass. Large sandstone or wooden mullions divide the windows into a number of lights; each light is divided into a number of small, diamond or rectangular shared panes by numerous cames. The glazing is thin and irregular, qualities which help diffract the colors of the stained glass windows and are basically of French, wall-faced pedimented dormer, or the standard Grouped casement type. Frames are either of sandstone or wood painted brown.

Front Facade (northeast)

The front facade may be divided into several sections: the two story main block comprised of five bays; a one and one half story, two bay wing projecting at a right angle from the northwest side of the main block; a one story two bay wide by one bay deep office which projects from the right angle formed by the wings; and a one and one half story, three bay wing continuing from the main section to the southeast.

The front entrance of Morrocroft (facing to the northeast) is articulated by a two story, gabled bay projecting from the central wing of the house. Walls are slightly battered. The vestibule is entered by a central doorless opening with a wide sandstone frame and sandstone Tudor arch with flared sides. Wrought iron and glass lantern with supporting bracket hangs over the entrance. The second story is pierced by a four light, leaded casement window, each light containing diamond shaped panes formed by cames. The southeast side of the entrance porch contains a similar window with two lights centrally placed on the first story and a small casement window on the second story near where the vestibule and main wing intersect. The interior of the vestibule is faced with large well-dressed sandstone blocks, has a wooden ceiling with exposed beams from which a lantern is suspended, and a slate floor. The northwest interior side contains a shallow niche with lintel. The door, with outer screen, is of wrought iron and glass and bears a stylized peacock framed by a leafy spiral vine pattern. Frame is of metal which forms a cable pattern; sill is of bronze.

A long wrought iron bell handle is located on the left side of the interior entranceway. The bay to the southeast of the projecting porch is pierced by a ground story sandstone frame window with four lights and transom while the second story contains a window with three lights. The southeast wing of Morrocroft is set back from the front wall of the main block, allowing room for a French window with transom on the first story, a window with two lights on the second story and a small casement window on the third story, all having sandstone mullions and surrounds. The bay northwest of the entrance projects slightly from the main block and is articulated by an oriel window situated between the first and second stories. A frieze running above the window’s twelve lights with diamond shaded panes bears grapevines whose fruit is being enjoyed by birds and animals. Below the glazing a larger four panel frieze contains harvest scenes and the daily activities of the country folk. These panels are enhanced by a molding of twisted cable and three rosettes. Below and to the right of the oriel window is a decorative diamond shaped grille bearing a squirrel surrounded by leafy vines and set into brick cut into a diaper pattern. The northwest side of this projecting bay is pierced by a casement window with two lights on the ground story.

The remaining bays in the main block consist of a bay pierced by a four light casement window with transom on the ground story and a three light window on the second story; a double light casement window is located on both stories of the end bay. The one and one half story wing which is at a right angle to the main block is marked by a narrow single casement window and a double light casement window on the first story, each with wood surrounds. A three light, wall face dormer window with wood surrounds and soldier course is centrally located above the first story fenestration. A high, wide garden wall extends from this wing; the brick is thin but is of a slightly darker color than the brick used for the house. Two brick steps lead to a centrally placed archway capped by a decorative brick keystone. The wood door has four panels and a wrought iron unglazed fan light with tracery. Low brick borders define the boxwood beds in front of the wall. A single story office with a steeply sloping gable roof and an end wall chimney projects from the intersection of the main block and the side wing. Its entrance facade, which faces southeast, contains a three panel frame door with upper glazed lights and a three light casement window with wood surrounds. The one and one half story wing on the southeast side of the main sections of the house is symmetrically articulated, it having three evenly spaced French windows with stationary transoms, interior screens and sandstone surrounds. Two double light, brick faced dormer windows with wood surrounds and soldier course are situated above the first and third ground story bays.

Southeast (Terrace and Garden) Facade

Two glazed floor length windows with sandstone frames, overhead wall lanterns, and exterior screen doors comprise the first story. The second story is pierced by two single casement windows with sandstone surrounds. An end-wall chimney with three brick stacks courses through the central section of this facade.

Southwest (Rear) Facade, facing Sharon Rd.

This facade may be divided into three sections. The main block’s (four bays) and southeast wing’s (three bays) bay and fenestration arrangement correspond roughly to that of the front facade. A one and one half story northwest wing contains two bays. The southeast wing of this facade contains three French windows with fixed transom, sandstone frames and interior screen doors. The attic floor is articulated by a double light dormer window with wood surrounds on the first and third bays. These flank a tiny wood frame casement window located directly under the eaves. The southeastern most bay of the main block contains a first story four light casement window with transom and a three light casement window with double transom on the second floor. frames and mullions are sandstone. This bay projects from the common wall line of the main block to include a first story French window with transom and a second story double light casement window on its northwest side. A French window with transom and narrow glazed side doors with transoms and inner screen doors corresponds in placement to the entrance bay on the front facade. The adjoining bay contains a first story five light casement window with transom. A bracketed lantern extends from the wall between these bays. Metal rollers placed at intervals between the first and second story indicate an awning covered the terrace in this section at one time.

The second story portion over these two bays is sheathed in shingle siding and is pierced by a two light casement window, and a narrow casement window situated near the projection of a bay on the northwest end of the main block. The attic story of the shingle-sided section contains three evenly spaced true dormer windows. Wood surrounds and mullions characterize the fenestration of the second and attic stories. A six-sectioned ground story bay window with transom comprises the final bay of the main block. This bay projects slightly from the main block. Fenestration has sandstone frame and mullions. The northwest one and one half story wing of Morrocroft is set back from the main block. The right angle formed by the intersection of these sections contains a side entrance porch formed by one free standing and two engaged wooden piers with brick pier bases. Pegged wooden braces extend from these piers to support a second story balcony with turned balusters and three piers with perched, wood stylized vultures. The entrance from this porch is located on the northwest end of the main block of the house and consists of a wooden door with six panels and an exterior screen door. A two light casement window is located on the second story, directly over the entrance, while a smaller two light casement window defines the third story. Both have sandstone mullions and surrounds. The wing northwest of the main block of the house contains a pedimented door set into the roof leading onto the second story balcony. The lower half of the door with exterior screen door is frame, the upper portion being glazed. The remaining bays in this wing are pierced by a three light casement window and a four light casement window on the ground story and two pedimented dormer windows with two and three lights respectively. Fenestration in these bays has wood surrounds and mullions. The northwest end of this wing is one bay deep and contains a first story double light casement window which has been boarded over and a narrow casement window on the second story. A wide end wall chimney with three clay pots also articulates this end.

Service Wing Complex

A rectangular walled service court forms the extreme northwest side of the manor house and may be entered from the grounds both on the northeast (driveway) side and through a small pedestrian arched entrance (with exaggerated brick keystone) on its northwest side. The interior of the court contains a central paved area. The southeast side (rear side of the front brick garden wall) contains a shingle roof carport which is not original to the house. The 1927 plan of the residence allocated this area to a drying yard. Steps to a large full basement are located on the northeast end of the service building. The building complex itself is composed of the rear facade of the wing which extends at a right angle from the main block, a servants’ hall which projects from the joining of the two wings at their northwest side, and an added laundry facility extension which completes the southwest side of the court. The right angle one and one half story wing (southeast side of the court) contains three bays. The first is pierced by a ground story four light casement window and an attic three light dormer window, both with wood surrounds and mullions. This bay was originally designated as a laundry room as shown by the plan. A rectangular screened porch comprises the area in front of the second and third bays, filling in the area formed by the junction of the southeast and southwest sides of the court. A screen door, facing northwest, leads into the porch. The house proper is entered by a three panel, upper glazed door in the second bay of this wing. A double light casement window comprises the third bay of this window. A small four light casement attic window is located above this area. The southwest one story facade of the court consists of two bays: an entrance door end a double light casement window.

Wood frames are employed consistently. This section of the court (southwest) was extended at a later date to include a nine bay laundry facility which has a lower, shingle gable roof. The laundry section is built of wood painted dark brown to match the trim of the main house and is half timbered with wood insets (to simulate true half timber construction) on the lower section. Seven of the bays are pierced by casement windows; two contain entrances. The third and seventh bays contain a tri-paneled frame door with upper glazed section and an exterior screen door. These entrances are reached by two brick steps and side rails and have bracketed gabled overdoors with simulated half timbered pediments. Windows have double lights with the exception of the sixth bay which is articulated by a three light casement window. Wood mullions are painted brown. The northwest, exterior end wall of the court has been altered to contain a small casement window with brick header to illuminate the laundry room. The southwest exterior side of the court consists of the rear of the laundry and the servants’ hall. The rear of the laundry contains a louvered vent; a three light casement window comprises the rear bay of this servants’ hall.

Interior of the Manor House

The exterior of Morrocroft, as would befit a manor house, is stately and imposing. Its interior, while fitted with dignified and rich detailing, possesses a human-scale quality which survives the house a true domestic character. Lindeberg purposefully sought to include the domestic element in the design of his large country houses. In the introduction to Lindeberg’s and Albro’s publication, Domestic Architecture, the large dwelling and the cottage are compared: “Even the large house in the country should not merely be a place for the reception of visitors; it should be a dwelling for a family, and it should express the domestic feeling, as surely and straightforwardly as the cottage.”6 The first floor of the residence contains an entrance hall, living room, sun-room, library, stairhall, powder room, and dining room. The kitchen complete with pantry and cold room, a servants’ hall, laundry, and office are also located on this floor. No staircases lead to a second story comprised of six bedrooms with baths, a boudoir, linen room, and pressing room. There is an extraordinary amount of closet and shelf space or this floor. A staircase leads from the second floor hall to a third story located in the central block of the house. It contains a bedroom with bath and two large cedar lined storage rooms.

First Floor

A large rectangular hall may be entered both from the front vestibule and the rear terrace side of the house. The most singular feature of this room is the front entrance wall, two thirds of which is paneled in Norwegian pine; the upper portion is plaster as are the other walls and ceiling. The door is trimmed with pine, has cable trim surround, and is framed by fluted pilasters carrying an entablature with broken pediment. The frieze is decorated by a central, fluted keystone flanked by carved swans; the pediment is enriched with a shell pattern and leaf and tongue. A pine mantel fireplace with rectangular opening and a carved over mantel with carved volutes and a broken pediment is located in the northwest wall. The frieze is comprised of cross-banded sheaths of wheat and a central swag. The dentil work and triglyphs and metope decorate the cornice. The shouldered architrave is framed with bead and reel borders, while the inner surround and hearth are of black-green marble. The interior of the fireplace is terracotta molded into the shape of shamrocks. The hall’s plaster cornice bears a floral decoration. The baseboard is pine. Wide oak pegged boards comprise the floor.

A large, rectangular living room may be entered from two six panel doors in the southeast wall of the hall. Door hardware consists of polished steel box locks engraved with a floral motif, melon shaped knob (pull on opposite side of door), and a long key and chain. A white marble mantel is centrally located in the southeast wall of this room. Its rectangular opening is framed by pilasters with garlands and acanthus decorated capitals. The center tablet of the frieze is in fairly high relief and is decorated with an allegorical depiction of Cupid bound. A nymph holding Cupid’s bow and two figures running toward them with garlands complete this panel. It is flanked by foliated scrolls and small panels bearing love birds. The hearth is of black slate, while the interior of the fireplace is comprised of thin bricks set in a herring bone pattern with thick bands of mortar. The room has a deep cornice which includes a band of acanthus leaves and high relief daisy heads, cable pattern with rosettes, and molding of leaf and tongue. The paneled walls are wood painted to resemble plasterwork; baseboard has a stylized foliated border. The oak floor is parquet. A French window with stationary transom and sandstone surrounds in the living room’s southeast wall opens into a rectangular sun-room. The 1927 plan shows part of this area was to be used as a flower room; in actuality the room was never realized. The most distinctive feature of the sunroom is the large, multi-tinted glass, leaded trench windows which instill the room with a soft, muted light. A white and earthy red marble fireplace, in projecting chimney breast is located in the center of the southeast wall. The frieze is comprised of a central oval tablet of white marble trimmed in red marble which bears the head of Bacchus flanked with horns of plenty. Enriched ovolo (egg and dart), and stylized leafy borders and wheat ear drops also decorate the frieze. The hearth is black slate; the interior of the fireplace is incised black metal. The sunroom’s cornice contains decorative brackets with soffits bearings rosettes and a molding of enriched ovolo. The floor is of wide pegged oak planks.

The hall with spiral staircase is entered from the northwest side of the entrance hall. A slender, polished steel rail with delicate ornamented balusters set into the sides of the wood steps leads to the second floor hall. The stairwell is illuminated by a large, tinted-and-diamond panel oriel window which is flanked by heating grilles bearing highly decorative ironwork. The cornice in the first floor hall bears the cable motif. The floor is pegged plank. The Norwegian pine paneled library leads from the southwest wall of the stairhall. Walls are lined with cable trimmed bookcases and lower storage areas (over door shelves as well). The southwest wall contains a large window with transom, and sandstone mullions and frame. Window screens, as found throughout the house, can be hidden in the frames. A pine mantel, which is similar to the mantel in the entrance hall, is located in the southeast wall. The mantel has a rectangular opening with a black-green marble surround, shouldered architrave, carved foliated frieze and cornice, and a simple overmantel panel. Hearth is of marble slab, while the interior of the fireplace is constructed in the brick herring-bone pattern. The library’s cornice work consists of pronounced dentil work, and enriched ovolo. Plank floor is pegged. The rectangular dining room with southwest wall bay window is reached from the northwest wall of the stairhall. Walls are paneled wood painted to simulate plasterwork, as found in the living room. The wall finish consists of gold leaf enriched ovolo, enriched cyma reversa, and foliated cornice, a gold leaf chair rail with a leafy border bearing rosettes, and gold leaf panel trim with the cable motif. The floor is parquet. Hardware on the six panel doors is similar to the living room doors. A white marble mantel with rectangular opening and ochre and tan marble surround framed by pilasters bearing a ribbon and garland decoration is located in the northwest wall. The frieze bears a center tablet in relief with a scene of putti letting a bird escape from a box; this is flanked by swans, putti with birds, and a lower, fluted border. The paneled overmantel with ovolo and floral cold leaf trims has a broken pediment which terminates in volutes flanking a decorative shell; both are painted in gold leaf. The kitchen complex spans a substantial area of the first floor and includes a “large pantry and cold room.” The kitchen and pantry counter tops are red, while floors are fashioned in black and white linoleum squares. Remodeling would appear to date from the 1960s.

A one room office may be entered from either hall or an exterior door; the 1927 plan does not show the opening in the office’s northwest wall, although it appears original to the house. The door hardware consists of metal plates in the shape of a frontier man with coonskin cap, musket and powder horn, and a cabled handle. The paneled wall cabinets and simple wood cornice and baseboard line the office. The floor is pegged plank. The northeast wall contains a fireplace flanked by open shelves and under cabinets. The simple wood mantel has a rectangular opening, dentil work trim, a black slate hearth and trick herring, bone pattern interior.

Second Floor

The southeast section of this floor contains the master bedrooms and a boudoir which locks offer the formal gardens. The boudoir was converted into an “ideal dressing room” by the Morrisons’ daughter, Mrs. James J. Harris.7 The only feature that the 1927 plan does not show is the large, double folding door bath alcove located in the northwest wall. The tub and alcove walls are sheathed in pink marble with gray veining. A small chandelier hangs overhead. Smaller window alcoves in the southwest and northeast walls contain respectively a pink, gray-veined marble sink with ornamental gold sea creature fixtures and a mirrored dressing table held by stylized floral brackets. Wall cabinets, shelves, and closets line the walls. A projecting gray marble mantel with white veining and curved opening comprises the center of the southeast wall. Pilasters are cable fluted with upper cartouche, while the center of the frieze bears a decorative shell. The hearth is gray and white marble with a white marble inset.

A hall from the boudoir leads into what was originally Mrs. Morrison’s bedroom. This room overlooks the spacious lawn on the southwest side of the house. Its dominant feature is a white marble fireplace with rectangular opening, bead and reel surround, and pilasters with terms on high pedestals. The frieze contains a center relief panel with seated allegorical figures. This tablet is flanked by fluting and end love birds. Other decorative molding includes acanthus and beading. The hearth is black slate, and the fireplace interior is black incised metal. What was originally Mrs. Morrison’s bedroom is located at the front of the house. Its floor has been left uncarpeted and consists of small hardwood boards. This flooring is probably standard to the second floor. The bathroom with parquet veneer floor lies directly over the front vestibule. Its white marble sink with metal and Lucite fixtures is employed in the remaining bathrooms on this floor.

A hall which runs the length of the northwest half of Morrocroft links the remaining four bedrooms, linen room and pressing room. Plaster cornice work in the cart of the hall reached directly from the spiral staircase is elaborate and consists of a border of various flowers such as the rose and fleur de lis. This molding is sandwiched by the cable motif. Trim continues on the ceiling which bears a foliated scroll pattern. Noteworthy features in the remaining bedrooms include marble or wooden fireplaces The bedroom which faces the spiral staircase landing has a southeast wall pine mantel with rectangular opening and black slate surround. Pilasters are decorated with wheat ear drops and upper acanthus consoles; the frieze bears a central carved shell flanked by foliated scrolls and bead and reel. The cornice work has the egg, and dart and stylized leaf motifs. The hearth is black slate, while the fireplace interior is composed of tricks laid in the herring bone pattern. The bedroom, located beside a staircase leading to the third floor, contains a northwest mantel of white marble panel of the gray and green marble panel inserts. She center, white marble panel of the frieze is decorated with crossed flaming torches and twisted ribbon; the frieze ends bears the same motif on a smaller scale. The hearth is black slate. The fireplace interior is brick laid in the herring bone pattern.

The northwest wings of this story are reached by a two step down break in the main hallway at the point where the third floor staircase rises; the hall ceiling becomes lower. This section of the house may also be reached from the ground floor by a single flight back staircase. The pine balustrade on the second floor consists of turned balusters, simple handrail and turned acorn posts. The west corner bedroom has a northwest wall mantel of variegated gray, red, and white marble with rectangular opening, pilasters with cabled fluting, and frieze adorned with interlocked circles. The same type marble comprises the hearth. The northeast corner bedroom has a mantel in the northeast wall, which consists of a similar multi-colored marble and shape as the above mantel. Pilasters bear wheat ear drops, while the central panel of the frieze contains a stylized flower. The hearth is white marble, bordered by gray, red; white veined marble panels. Ceilings shapes and heights in the manor house are varied. While the first floor has traditional flat ceiling, the second floor master bedroom, boudoir, and the northeast end bedroom have plaster barrel vault ceilings. A section of the second floor hall is also barrel vaulted. Ceiling heights in the main rooms and hall or the first floor are 10’9”; kitchen and office ceilings are 9′ and 8’7″ respectively. Second floor ceiling heights are: boudoir, 9’2″; master bedroom, 12’6″; central southeast side bedroom, 9’2″; remaining three bedrooms and linen room, all 9′, and pressing room, 8’11”. Bathroom ceiling heights are 8’11”, while the halls range from 9’8″ to 8’6″ to 7’10”.

Third Floor

Admittance to the third floor could not be obtained from the owners for this report.

Utility Buildings

Garage

A one and one half story brick garage with steep gable located on the grounds to the north of the house. A central, one story bay with gable roof projects at a right angle from the southeast side of the main block. The brick, terracotta shingles and gutters are similar to the manor house: the structure appears to have been built at the same time as the house. The land rises to the southeast.

The garage door side of the building (northwest) contains three bays. The wide middle bay on the ground story is comprised of a set of hinged doors flanked by two side doors; the smaller end bays also contain hinged doors. Each section of the doors has three wood panels painted brown with an upper glazed portion. Three evenly spaced double light dormer windows and a small dormer window located between the second and third bays characterize the attic story. Window frames and mullions are wood painted brown.

The northeast facade is marked by an exterior single flight brick staircase with brick side. A three panel, upper glazed door is located in an opening in the side of the stairs on ground level. The remaining bay on this story has a double light casement window. A small flight of stairs with metal rail leads to a basement door. The attic story contains a centrally-located door flanked on each side by a casement window. The main block roof on the rear (southeast) facade slopes and flares to a point 4’9″ from the ground level. A single stack chimney with corbel cap is located in the main block to the right of the projecting bay. The right end bay of the main block (under the chimney) is pierced by a round level double light casement basement window. The left end bay of this block contains a small ground level casement window placed near the junction of the main block and projecting bay. The central, projecting bay contains a low set, six light casement window with wood mullions and surround. The southwest, one and one half story facade has two bays. The left bay is pierced by a four light casement window on the ground floor and an attic double light casement window. A double light casement window is situated near ground level in the right bay.

Summerhouse

The red brick raised floor of a summerhouse is located on the northwest side of the manor house. Small metal post holes are found at intervals alone the edge of the cruciform shared floor. According to the caretaker the structure had a terracotta roof supported by wooden posts and was screened. Large awnings could be rolled down for shelter from the sun or inclement weather.

Gardenhouse

A single bay, square sided brick garden house with composition shingle, hip roof stands on the grounds due south of the main house. The brick, although similar to that of the manor house, is not identical and is laid in running (stretcher) bond. The brickwork, symmetrical design and detailing indicate the structure is not original to the property. The entrance facade (north) contains a centrally-placed archway with four panel wood door. The east facade contains an arched window which has been boarded over. A three light window with stationary center light and side casements pierces the south wall, while the west wall is blank. The red brick interior has a ceiling with exposed beams which radiate to a circular boss.

NOTES

1 Harrie T. Lindeberg, Domestic Architecture of H. T. Lindeberg, with an Introduction by Royal Cortissoz, New York: William Helburn, Inc., 1940. See the list of clients, pp. 305-310, Morrocroft is illustrated on page 71.

2 Barbara McAden, “Family’s English Manor Gains Lighter Look”, The Charlotte Observer, September 29, 1963, Section D, p. 1.

3 L, C. Albro and H. B. Lindeberg, Domestic Architecture, Cambridge, MA: University Press, for private distribution by the authors, 1912, Introduction, Albro and Lindeberg were partners from 1906 to 1914. See the acknowledgement in Lindeberg Domestic Architecture.

4 Lindeberg, p. 70.

5 Camden.

6 Albro and Lindeberg, Introduction.

7 McAden, p.1.