Croft Schoolhouse

S. W. Davis House

This report was written on 30 March 1992

1. Names and locations of the properties: The properties known as the Croft Schoolhouse and the S. W. Davis House and Outbuildings are located on Bob Beatty Road in the unincorporated area known as Croft, Mecklenburg County, North Carolina.

2. Names, addresses, and telephone numbers of the present owners of the properties: The owners of the properties are:

Investors Real Estate Investment Company

P. O. Box 51579

Durham, NC 27717

Local Agent: John A. Gilchrist

East West Partners of Charlotte

8800 Davis Lake Parkway

Charlotte, NC 28269

Telephone: (704) 598-0063

Croft Schoolhouse

Tax Parcel Number: 027-201-07

Deed Book 5744, page 542

S. W. Davis House and Outbuildings

Tax Parcel Number: 027-201-06

Deed Book 5744, page 542

3. Representative photographs of the properties: This report contains representative photographs of the properties.

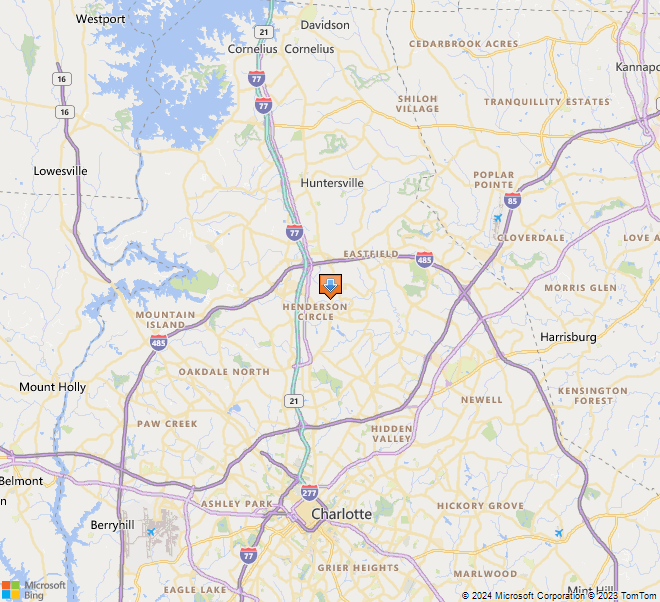

4. A map depicting the location of the properties: This report contains maps which depict the location of the properties.

5. Current Deed Book References to the properties: The most recent deeds to the Tax Parcels, as listed in Mecklenburg County Deed Books, are given above in item 2.

6. A brief historical sketch of the properties: This report contains a brief historical sketch of the properties prepared by Paula M. Stathakis.

7. Brief architectural descriptions of the properties: This report contains brief architectural descriptions of the properties prepared by Nora M. Black.

8. Documentation of why and what ways the properties meet criteria for designation set forth in N.C.G.S. 160A-400.5:

a. Special significance in terms of history, architecture, and /or cultural importance: The Commission judges that the properties known as the Croft Schoolhouse and the S. W. Davis House and Outbuildings do possess special significance in terms of Mecklenburg County. The Commission bases its judgment on the following considerations:

1) the community of Croft was an important early railroad stop between Charlotte and Huntersville;

2) the original two room, two story Croft Schoolhouse was constructed ca.1890;

3) the ca. 1910 two story addition to the Croft Schoolhouse was built by Neil Barnett, a local carpenter;

4) the Croft Schoolhouse served the community until the 1930s;

5) S. W. Davis became a prominent farmer, and with his brother, Charles, a retail merchant;

6) the S. W. Davis House was built ca.1903 by Neil Barnett;

7) the S. W. Davis House is a fine example of a Queen Anne style farmhouse;

8) the largely intact exterior and interior of the S. W. Davis House show the early 20th century pattern of living in rural Mecklenburg County;

9) the two outbuildings, the flower house and the spring house, are fine examples of early 20th century brickwork; and

10) the Croft Schoolhouse, the S. W. Davis House, and the outbuildings provide a set of timeless landmarks in the changing landscape of northern Mecklenburg County.

b. Integrity, design, setting, workmanship, materials, feeling, and /or association: The Commission contends that the architectural descriptions by Nora M. Black included in this report demonstrate that the Croft Schoolhouse and the S. W. Davis House and Outbuildings meet this criterion.

9. Ad Valorem Tax Appraisal: The Commission is aware that designation would allow the owner to apply for an automatic deferral of 50% of the Ad Valorem taxes on all or any portion of the property which becomes a designated “historic landmark.” The land has been divided into new Tax Parcels so recently that the Tax Office has not recorded the new current appraised value of the improvements, the current appraised value of the land included in the Tax Parcels, the total appraised value of the properties, and zoning.

Date of preparation of this report: 30 March 1992

Prepared by: Dr. Dan L. Morrill in conjunction with Nora M. Black

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission

The Law Building, Suite 100, 730 East Trade Street

P. O. Box 35434

Charlotte, North Carolina

Telephone: (704) 376-9115

Historical Overview

P. M. Stathakis

The Croft Community is located on NC 115 along the Norfolk Southern Railroad, between Charlotte and Huntersville. Croft was once described by a train conductor as “a mud puddle between Charlotte and Statesville.”1 The Croft School and the S.W. Davis House are two of the twenty-one contributing structures and sites of the National Register Historic District that make up the small community.2 In addition to the school and the Davis House, other principal structures in Croft include the S.W. and C.S. Davis General Store, the C.S. Davis house, and the Robert Beatty House. Minor features include warehouses, storage buildings, barns, a smokehouse, and a flower house (located adjacent to the S.W. Davis house).3

The focal point of Croft is the S.W. and C.S. Davis General Store, established in 1908 by brothers Silas Winslow and Charles Spencer Davis. The Croft District is, as a whole, representative of the time when Mecklenburg was still largely rural, and when a significant part of its economy was based on agriculture. During this time, country merchants, such as the Davis brothers, controlled part of this rural economy by acting as suppliers, middlemen, and bankers to area farmers.

Croft and its general store would have never developed without the railroad. The tracks that run through Croft, in front of the general store, the S.W. Davis House and the school house were formerly part of the Atlantic, Tennessee, and Ohio Railroad. This line, which connected Charlotte to Huntersville and points beyond, was completed in 1863. Shortly after its completion, portions of this track were torn up and re-laid to supplement the wartime needs of a railroad between Greensboro, NC and Danville, VA. After the Civil War, the A.T. & O. leg between Charlotte and Huntersville was restored in its entirety by 1871. This railroad has been aptly described as the “spine” of the subsequent industrial and commercial development in Northern Mecklenburg in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.4

The railroad and the general store in turn-of-the-century Mecklenburg County, and in the south as a whole, were tremendously important social and economic forces. The construction of railroads changed the outlook of southern agriculture and the situation of the yeoman farmer. Railroads brought the market closer to the farmer, and it seems that farmers could have reaped great financial benefits from this arrangement. However, many farmers ultimately found themselves trapped between the railroad and the merchant. Railroads brought cheap manufactured goods, that undercut regional monopolies, and effectively put most domestic manufacturing and artisans out of production. Rural families became less reliant on domestic manufactures, and more dependent on area merchants who extended credit on purchases. Farmers were also often vulnerable to the credit system provided by local merchants which required that credit customers provide a cash crop as security on their account. In Mecklenburg County, as in many other parts of the south, farmers were consequently forced to shift from subsistence farming to cotton cultivation to satisfy merchants. Small farmers were always in debt to merchants for seed and fertilizer, and by the turn of the century, cotton became the crop that chained the farmer to the merchant in the cycle of debt and obligation.

It was in this economic climate that the Davis brothers established their store. The general store had a cotton gin on site to process bales for local farmers. According to the Annual Accounts of the Estate of Silas Davis, this gin pressed 500 pound bales with processing fees ranging from 22 l/4 cents per pound to 25 cents per pound. Part of the cotton ginned by the Davis brothers was sold directly to area mills and cotton brokers, and could be distributed to these customers easily by train.5 The Davis general store also sold agricultural supplies, general merchandise and provided the first telephone in Croft.6

Silas Davis combined farming and retailing throughout his adult life. The 1900 and 1910 manuscript census lists Silas Davis as a farmer and lists his brother Charles as a retail merchant.7 According to Helen Brown, daughter of Silas Davis, her father grew cotton, corn, wheat and oats. Silas Davis routinely kept three or four tenants on the farm, but much of the agricultural labor was performed by his children. During picking season, each child was required to pick a certain quota of cotton, and if this quota was not met, Davis would pop them once with a hickory stick for each pound that was lacking. Davis also raised several different kinds of fowl, goats, sheep, hogs, cows, mules, and horses. Every week, Silas Davis slaughtered a cow and sold the fresh meat in the store.8

The two story Queen Anne style farmhouse where the S.W. Davis family lived was built in 1903 by Neil Barnett, a local carpenter. Silas and his wife, Nannie J. (Nancy Black) Davis, whom he married in 1895, raised their ten children in this house. Silas and Nannie occupied a smaller house that was situated behind the large house while it was being built. The Davises told their children that this small house was located next to a fig tree in what became their back yard. This house was torn down after the two story house was completed.9

The Croft School, located next door to the S.W. Davis house, was originally built as a two room, two story schoolhouse in 1890. A two story addition, completed in 1910, enlarged the schoolhouse to four rooms, with four teachers instead of two. Silas Davis had lobbied for a schoolhouse expansion for several years, but the county school board was unable or unwilling to accommodate his wishes. Davis had the addition built at his own expense and billed the school board for the construction costs for which he was promptly reimbursed. The 1910 addition was built by Neil Barnett.10

In its early years, the Croft School served as a combined elementary and middle school. When the building had only two rooms, grades one through nine were taught there. By the 1920s, in its expanded version, grades one though seven were taught at Croft. Although students were grouped according to grade, teachers had more than one grade per classroom. During most of Helen Brown’s tenure at Croft there were two students in her grade, and by the time she graduated from the seventh grade, the size of her graduating class had doubled to four. Students who finished at Croft were sent to Huntersville High School.11

Students who attended the Croft School in the l910s and 1920s remember that the school never had electricity or running water. Students had to bring their lunch from home and they were also required to bring their own drinking glass. Each day, different children were chosen to go next door to the Silas Davis house to pump the drinking water for school. It took several trips and several buckets full to meet the schools daily drinking water requirements. However, the pupils looked forward to having their turn to escape class for a few minutes to pump water. Two outhouses were located behind the school, one for boys, the other for girls. In the winter, the school was heated by a wood stove.

Since the school was close to the general store and the railroad tracks, teachers and pupils became accustomed to the seasonal whistle of the cotton gin and the daily noise of trains. Three northbound trains passed through Croft each morning and three southbound trains passed through each afternoon. Teachers and students were so used to the noises that marked the rhythm of life in Croft, that the trains and whistles frequently went unnoticed.13

Nena Thomasson Davis came to teach at Croft in 1925. She was a native of northern Mecklenburg County, and had completed two years at Huntersville High School in addition to ten years of public school at a one teacher school on Concord Road. Because her family could not afford to send her to college, the principal at Huntersville High School encouraged her to attend a six week summer course to study for a provisional teaching certificate. Nena Thomasson attended Lenoir Rhyne College for six weeks to earn her certificate, and before her studies were complete, she was approached by several individuals who were desperately trying to recruit teachers for rural schools. She taught her first year in Leagrove, NC (in Harnett County), but she missed her home, and she soon returned to Mecklenburg County to teach. She taught at Croft for seven years. During this time, she also attended Davidson College where she earned her a certificate in teaching, a requirement for all teachers in Mecklenburg County.14

In 1931, Nena Thomasson married Charles Spencer Davis. She had to give up teaching because the school board did not permit married women to teach. Within a few years, Charles Davis led a movement to build a new school house in Croft. The new schoolhouse (now the VFW post) was built in the 1930s across the road from the original school, which has stood empty ever since.15

Notes

1 Interview with Nena Thomasson Davis, by Paula M. Stathakis, February 1992. According to Nena Thomasson Davis, Croft was named for Croft Woodruff, a major landowner in the area. The railroad authorities chose Mr. Woodruff’s name when they created a new railroad stop between Charlotte and Huntersville.

2 National Register of Historic Places Registration Form for the Croft Historic District. Prepared by Richard Mattson and William Huffman, July 1990, section 7 page 2.

3 Ibid. See section 7 pages 2-7 for a complete inventory of all structures and sites of the Croft Community.

4 D.L. Morrill, Survey and Research Report, S.W. and C.S. Davis General Store. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Properties Commission, October 1, 1980.

5 These figures are accurate for the year 1925 and are derived from the Annual Accounts of The Silas Winslow Davis Estate filed in 1925 in Record of Accounts Book 20 page 238, Mecklenburg County Court House.

6 Survey and Research Report, S.W. and C.S. Davis General Store, Charlotte Mecklenburg Historic Properties Commission, October 10, 1980.

7 Twelfth Census of the United States, 1900. Manuscript for Mecklenburg County; Thirteenth Census of the United States, 1910. Manuscript for Mecklenburg County.

8 Interview with Mrs. Helen Davis Brown by Paula M. Stathakis, February, 1992. One of the tenant farmers lived in the flower house.

9 Ibid. The Davis children were Alma Davis Hucks, Naomi Davis Lewis, Bruce Hill, Mattie Rebecca, Silas Washington, Charles Edward, Helen Davis Brown, Carl Wilson, Ruth Virginia Davis Wallace, Catherine Davis Marcus, and John Woodrow. Mattie died when she was nine, the rest of the children survived to adulthood. Helen Brown recalled that as there were so many men in the family, she spent a great deal of time ironing shirts. The Davis children used to joke that Silas and Nannie ran an “old folks home” because elderly aunts and uncles as well as several cousins came to live in the Silas Davis household for extended visits. Charles Davis was also a member of the Silas Davis household until his brother died, in 1925.

10 B.C. Fincher, “Change Comes Slowly to Croft”, Charlotte Observer, April l9, 1989. Good Neighbors Section, p. 22. Interview, Helen Brown.

11 Interview, Helen Davis Brown; Interview, Nena Thomasson Davis. In one of the lighter moments during the school day, Bruce Davis, one of Silas Davis’ sons, recalled that he was once dangled out of a second story window by his heels by some of the older school boys, B.C. Fincher, “Change Comes Slowly to Croft.”

12 Interview, Helen Davis Brown; Interview, Nena Thomasson Davis; Interview with Mr. James and Mrs. Rosa Hucks Davis by Paula M. Stathakis, February, 1992.

13 Ibid. B.C. Fincher, “Change Comes Slowly to Croft.”

14 Interview, Nena Thomasson Davis.

15 Interview, Nena Thomasson Davis.

Architectural Description

Croft Schoolhouse

Nora M. Black

The Croft Schoolhouse is located in the unincorporated area known as Croft in north Mecklenburg County. The Schoolhouse is on the east side of Bob Beatty Road (State Road 2483). The front or west facade of the Schoolhouse is parallel to Bob Beatty Road; the rear or east facade overlooks land slated for development as part of the Davis Lake subdivision. The Schoolhouse is located on the east side of a square lot of 0.908 acres owned by Investors Real Estate Investment Company; it is currently unused.

The late 19th century part of the Croft Schoolhouse is the north half of the building. The south half of the building was constructed in the early decades of the 20th century. Although both halves look similar, differences in building materials can be seen. The ground plan of the Croft Schoolhouse is a massed plan with two units of width and depth. The building presents a symmetrical elevation to Bob Beatty Road. The two-story facade dominates the front view in spite of the high hipped roof. A one-story hipped roof porch runs the length of the front of the Schoolhouse. This plain, utilitarian front or public side of the building is enlivened by two cross gables.

Exterior

The siding is lapped horizontal boards with vertical corner boards. The siding on the older north section is narrower than that of the newer south section. A former student, Mr. Donald Penninger, Sr., remembers a time approximately 57 years ago when the north part of the building was painted red while the south part was painted white. The siding is original and mostly intact. Some pieces are missing above the front porch. There is also some deterioration of siding around the north chimney on the back of the building. The foundation consists of original brick piers infilled with newer brick in the north section; the south section has a brick foundation laid in running bond.

The front elevation is divided into two symmetrical bays defined by a strip of vertical molding. Each bay has a single window on the second floor over a single door on the first floor. Each bay also has a centered cross gable with a large diamond-shaped vent. The steep pitch of the hipped roof tends to unify the two sections. The dark gray composition shingles are old and curled; their three-sided tabs lend the appearance of hexagonal tiles on the roof. The roof of the front porch is covered with rusty but intact metal roofing material. The two cross gables and the boxed eaves have a moderate overhang.

Some of the windows in the Croft Schoolhouse contain the original leaded glass; most are 6/6 double hung wooden sash. Pairs of 6/6 windows occur only on the east or back facade. In the older section, the east facade has one pair of 6/6 windows on both first and second stories. The newer section has two pairs of 6/6 windows on both stories. Many windows have broken lights. In some cases, the entire sash is missing. The window surrounds in the older section are wide boards and not elaborate; however, the windows in the newer section have simple decorative moldings. The only exceptions to the 6/6 windows are two pane square windows located on the first floor. One is near the southwest corner of the building; the other is near the northwest corner.

The north wall has three 6/6 windows on both first and second stories. The south wall has two 6/6 windows on each story. The east wall of the building has two exterior masonry chimneys. The older north chimney is constructed of red/orange brick but it has collapsed to the level of the cave. The newer south chimney is constructed of red/brown brick. Some of the bricks of the south chimney have fallen too, but it still rises well above the level of the cave. Each chimney served two classrooms – one room upstairs, one room downstairs.

The entry porch on the west facade is a one-story hip-roofed porch with three turned wooden posts and two rough cedar posts. The south corner post is missing altogether. The two turned posts on the older section of the porch have square bases and Doric capitals. The early 20th century post has both a square base and capital. The outline of a classic dentil molding is evident in the red paint of the architrave of the older porch section. There is no evidence that such a molding ever existed on the newer section of the porch. The porch has tongue and groove flooring of same width boards; much of the wood on the south end is deteriorated. The steps leading to the porch have been removed. Each section has a single door opening into a vestibule. The door on the older section had an upper panel of glass (now missing) over a wooden panel. The newer section has a six panel wooden door; the doorknobs are missing.

Interior

The interior of the Croft Schoolhouse has not been modernized. It is remarkably dry inside considering the amount of glass missing from the windows. Some old bed frames, tractor tires and miscellaneous items are in the building. Both sections of the building have tongue and groove floors; however, the boards in the older section are wider than those in the new section. The stoves that once heated the classrooms are gone.

The older north section has walls and ceilings covered with wide beaded boards. All four window openings on the south wall of this section were covered when the new section was added. If one entered the door to the vestibule of this section, the stairway would be to the right or south side. The newel on the first floor is fluted; however, the newel on the landing is plain. There are two small rooms on the north side of the vestibule. A five panel wooden door opens into the first floor classroom. Another opening for a door has been covered with narrow beaded boards. On the second floor of the older section, a door at the top of the stairway opens directly into the classroom. The east wall of the classroom is deteriorating around the chimney. A narrow room over the vestibule runs the length of the classroom. An opening in the ceiling of this room leads to the attic.

The newer south section of the Croft Schoolhouse has walls and ceilings covered with narrow beaded boards. The window surrounds in this section have some decorative molding. If one entered the door to the vestibule of this section, the stairway would be to the left or north side. The square balusters and newels of the newer section are simple in shape. There is one small room on the south side of the vestibule; shelves line the walls. The door from the vestibule opens directly into the classroom. Lack of paint on the classroom walls shows the locations of blackboards and bulletin boards. A door in the southwest corner of the classroom leads to a book room. On the second floor of the newer section, a door at the top of the stairway opens directly into the classroom. As in the older section, a narrow room over the vestibule runs the length of the classroom. In the southwest corner of the classroom, there is a small storage closet with a six panel door.

The Croft Schoolhouse did not have electricity or running water during the time it was used as a school. Electricity was added at some time as evidenced by the exposed wiring strung between porcelain brackets fastened to the ceiling. The electrical box was installed in the vestibule of the older section.

Another change to the Croft Schoolhouse occurred after World War II. According to Mr. Penninger, housing was so scarce that a family moved into the Schoolhouse.3 That might account for the wallpaper that is still fastened to the beaded board walls in some rooms.

Conclusion

The Croft Schoolhouse provides a solid architectural link to the early educational system in Mecklenburg County. Most of the original fabric is relatively unchanged and in fair condition. The Schoolhouse provided more than just an education setting. It also served as a community gathering place. Mr. Robert Houser, Jr., a Croft native, still speaks wistfully of the ice cream suppers that the Woodsmen of the World held at the Schoolhouse in the 1930s.4 The building could be used as an example of early classrooms. Perhaps it could again become a gathering place for the residents of Croft.

Notes

1 Interview with Mr. Donald Eugene Penninger, Sr., Croft native who attended school at the Croft Schoolhouse; 20 March 1992.

2 Interview, as in #1.

3 Interview, as in #1.

4 Interview with Mr. Robert Houser, Jr., Croft native who attended school at the Croft Schoolhouse; 20 March 1992.

S. W. Davis Outbuildings

Nora M. Black

The S. W. Davis House is located in the unincorporated area known as Croft in north Mecklenburg County. The house is on the east side of Bob Beatty Road (State Road 2483). The driveway running from Bob Beatty Road to the house runs near the southern edge of the tax parcel. The front or west facade of the house faces Bob Beatty Road; the rear or east facade overlooks a field that is slated to be developed as part of the Davis Lake subdivision. The house is located on an irregularly-shaped lot of 1.685 acres owned by Investors Real Estate Investment Company; it is currently leased as a residence. The house sits near the rear of the site with most of the acreage between the S. W. Davis House and Bob Beatty Road.

The S. W. Davis House is a Victorian House built in the Queen Anne style. The house is a subtype of the Queen Anne style called the Spindlework type. Houses built between 1860 and 1900, the last decades of the reign of Britain’s Queen Victoria, are usually referred to as “Victorian.” The advent of balloon frame construction, replacing heavy timber construction, simplified the home building industry making it easier to add bays and overhangs and to construct irregular floor plans. Industrialization in the United States allowed large factories to mass produce wire nails, doors, windows, siding, and decorative details. The growing railroad system carried these mass-produced items throughout the country.2 Although the S. W. Davis House displays some of the benefits of the era including the dormer with its decorative details and the decorated cross-gables of the varied roofline, the house is a simpler interpretation of the style than Queen Anne houses built in town. To see the contrast to the high-style, town version of the Queen Anne Style, compare the S. W. Davis House to the Overcarsh House or the Sheppard House (both located in Charlotte’s Fourth Ward).

The ground plan of the S. W. Davis House is a compound plan with irregular projections from the principal mass. The house presents an asymmetrical, two-story elevation to Bob Beatty Road. The front view is dominated by the one-story porch that runs across the front and part of the south side of the house. The shaped wood shingles in the gable ends add the wall texture variation that is common in the Queen Anne style. The hipped roof with lower cross gables is a common roof type found in this style.

Exterior

According to local accounts, the lumber used in the house was cut from woodlands on the property and milled on the site as well. Brick used for the chimneys and supporting piers is said to have been produced from the brick yard behind the Davis Store.3 The S. W. Davis Houses has three types of siding: original horizontal lapped-board siding, channel siding with a beaded edge, and wood shingles. The channel siding with beaded edge occurs only under the protective cover of the first floor porch. Wood shingles are used in the cross gable ends as a decorative element. The repeating three-row pattern of shingles consists of a bottom row of rectangular-cut shingles; diamond-shaped shingles form the middle row; triangular shingles form the last row. The gables have wide overhangs with cornice returns. The wide eave overhang is boxed and has shingle molding. Wide boards serve as a simple frieze wrapping the house at the level of the eaves. Wide corner boards terminate at the frieze. The exterior of the house is painted white; however, the paint has weathered and is flaking in many spots.

The hipped roof encloses a large, unfloored attic. The hipped ridge, which runs parallel to the front facade, is approximately 42 feet from ground level.4 Two interior brick chimneys with corbeled tops pierce the asphalt-shingled roof. The one-story kitchen wing, located on the east side of the house, has a single interior brick chimney that is no longer used for reasons of safety. A new metal chimney vents smoke from the wood-burning stove in the kitchen.

Many of the windows in the S. W. Davis House contain the original leaded glass. Most are double hung, 2/2 wooden sash with vertical mullions. Shutters believed to have been used on some windows are stored in a barn off the property.

The front elevation is three units wide with the widest unit being the two-story cross gable section located on the northwest corner. Each floor of the cross gable section has a single, centered window; a small window is centered in the gable end as well. The cross gable section does not project far from the face of the house. The front entry forms the center unit; a single square window completes the first floor of the front facade. The second story center unit is composed of a single 2/2 window. The second story unit on the southwest corner has a single pane, square window. The gable end of the attic story has the repeating shingle pattern described earlier. It also has a decorative spandrel with a sunburst pattern set over a row of spindles with knob-like beads. A dormer on the southwest end of the facade has the same ornament as the gable end. Decorative bargeboards complete the gable and dormer ends. A cross gable end on the south side and a dormer on the north side are finished in the manner just described.

The one-story porch extends across the front of the house and halfway across the south side of the house. The roof of the porch is supported by lathe-turned columns. The balustrade consists of graceful turned balusters. The porch is floored with tongue and groove boards; it has a ceiling of beaded board. Five deteriorated wooden steps lead to the porch. The porch roof is covered with rectangular pieces of metal roofing.

The front entry has a modern aluminum and glass storm door protecting the inner door. The wood and glass paneled inner door has applied millwork and incised decorative detailing. The hardware, with the exception of the dead bolt, appears to be original. The door surround has wide fluted boards and bull’s-eye corner blocks. A side entry opening onto the one-story porch has a similar door with one difference — the large pane of glass is surrounded by smaller rectangular and square panes of stained and pebble-textured glass. The second door is also protected from weather by a modern storm door.

The S. W. Davis House had a back porch on the south facade of the kitchen wing. The framework of that porch has been covered with siding to provide space for a bathroom and an enclosed back porch. The back of the house is unremarkable with the only ornament that of the east gable end of the kitchen wing.

Interior

The interior of the S. W. Davis House has not been modernized. Most of the historic fabric is not only intact but visible. The rooms have original moldings and original hardware for the wooden, five-panel interior doors. The door surrounds are fluted with bull’s-eye corner blocks. Walls throughout the house are of plaster with beaded board wainscot. Exceptions are the parlor which has plaster walls with no wainscot, and the kitchen which has horizontal beaded boards covering the walls. Beaded boards were also used for the ceilings. Pine flooring is used throughout the house.

The front door opens to a large center passage hall that runs the length of the house; an open staircase to the second floor is on the south side of the hallway. The front section of the hall is somewhat separated from the back section by a wall with a scalloped opening. The effect is that of a separate foyer at first glance. The stairway to the second floor hallway has a balustrade of simple lathe-turned balusters. The square, fluted newels on the first and second floors are topped with lathe-turned urns.

To the left (north side of the house) when standing at the front door is the parlor. Wide crown moldings decorate the plaster walls. The focal point of the parlor is the fire surround with rectangular mirror. The painted fire surround has slender Ionic columns on each side of the fireplace to support the shelf. Centered above each column is a lathe-turned post that supports a higher shelf. Applied decorations are primarily floral although a fan is centered in the main panel. The fireplace has been closed for many years; at one time it was used to vent a stove.

The second room on the north side of the center passage hall has closets on each side of the fireplace. The fire surround has slender posts supporting the single shelf. Beadwork, sawn in half, decorates the panel. This fire surround is much simpler in character than the one in the parlor. A door on the east walls opens into the kitchen.

The kitchen is contained in a one-story wing located on the east side of the house. As mentioned earlier, it has horizontal beaded board covering all four walls. The cabinets, sink, and appliances have been added over the years. The kitchen has a doorway on the south wall leading to a large pantry. The door to the enclosed back porch is also on the south wall. The enclosed back porch is located on the south side of the kitchen wing. A door on the west wall of the enclosed porch opens to the center passage hallway. A shed addition to the enclosed porch provides space for a bathroom. Originally installed in 1934 by the Davis family, it is currently being renovated to provide a new shower and to repair termite damage.

On the south side of the center passage hallway, there are two rooms. The small room in the southwest corner of the first floor has a simple fire surround with three undecorated panels and two lathe-turned posts supporting the shelf. A door to the south side of the fireplace opens into the room beyond the fireplace. That second room on south side of the hallway has a door (described earlier) opening to the side of the one story front porch. The original wooden fire surround has been replaced by a modern brick fire surround. Otherwise, the room retains its original details.

The staircase climbs from the center passage hall to the second floor. The long single-run staircase lands in the hallway on the second floor. The second floor hallway, like that of the first floor, runs the length of the house. There are two rooms on each side of the hallway. Fire surrounds on the second floor are simple and unadorned; turned posts support the shelves. All the second floor rooms appear to have served as bedrooms for the Davis family. The entrance to the attic is a set of steps in the northeast room. That room also contains an access door to the attic above the kitchen wing.

The S. W. Davis House was constructed without a central heating system. Electricity was installed in the 1930s; it appears that many of the fixtures installed then are still in place. The house now has a wood stove located in the kitchen. Insulated ductwork carries heat from the kitchen to one upstairs bedroom. The fireplaces are not used.

Flower House

A brick structure, called the flower house, stands on the south side of the S. W. Davis House. The front, or west, facade of the flower house runs parallel to Bob Beatty Road. The brick, said to have been made near the Davis Store, is laid in common bond with 6th course headers.6 The building has a wooden five panel door centered on the west facade. Large 2/2 windows would have admitted plenty of light for the plants. Thick vines of ivy have grown over most of the building.

Spring House

A brick structure, located to the southeast of the house, is said to be a spring house. The front, or northwest, facade of the building is set at an angle of approximately 45 degrees to the back wall of the S. W. Davis House. Constructed of brick laid in common bond with 6th course headers, the building has segmental arches of two rowlock brick courses over the windows and the door. The segmental arch over the door has deteriorated. The side walls have parapets that step down from front to back of the building in three steps. The top course of brick is corbeled. Two wing walls at the back of the building extend to the southeast. The space enclosed by the walls has metal roof. The building is currently used for storage by the tenants.

Conclusion

The S. W. Davis House is an intact example of a Spindlework, Queen Anne style house from the early years of the 20th century. The finishes and decorative details of the S. W. Davis House are typical of those found in farmhouses. It can provide insight into the type of houses that large farm families inhabited during the days when Mecklenburg County was one of the nation’s leading producers of cotton.

NOTES

1 Virginia & Lee McAlester, A Field Guide to American Houses (New York, 1986), 264-265. Ibid., 239.

2 Ibid., 239.

3 Interview with John and Mary Wilber, current tenants of the S. W. Davis House; 22 March 1992.

4 Interview, as in #3.

5 Bargeboards (or vergeboards) are projecting boards placed against the incline of the gable of a building; they are frequently decorated.

6 Interview, as in #3.

7 Interview, as in #3. Interview, as in #3.