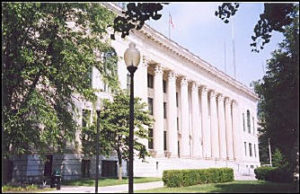

- Name and location of the property: The property known as the Mecklenburg County Courthouse is located at 700 East Trade Street in Charlotte, N.C.

- Name and address of the present owner of the property:

The present owner of the property is:

Mecklenburg County

400 East 4th Street

Charlotte, NC

- Representative photographs of the property: This report contains representative photographs of the property.

- A map depicting the location of the property: This report contains a map depicting the location of the property.

- Current deed book reference to the property: The most recent deed book reference to this property is found in Mecklenburg County Deed Book 610, p. 62, 70, and 76 and Mecklenburg County Deed Book 605 at pages 321 and 356. The Tax Parcel Number of the property is 125-03-201.

- A brief historical sketch of the property: This report contains a brief historical sketch of the property prepared by Emily D. Ramsey

- A brief architectural description of the property: This report contains a brief architectural description of the property prepared by Emily D. Ramsey.

- Documentation of why and in what ways the property meets the criteria for designation as set forth in N.C.G.S 160A-400.5:

- Special significance in terms of its history, architecture, and/or cultural importance: The Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission judges that the Mecklenburg County Courthouse possesses special significance in terms of Charlotte-Mecklenburg. The Commission bases its judgment on the following considerations:

- 1) The Mecklenburg County Courthouse is a representation of Charlotte-Mecklenburg’s economic growth, and the development of Charlotte as a regional textile hub and the largest city in North Carolina.

- 2) The Mecklenburg County Courthouse, erected in 1928 after a fierce battle between the city of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County, is a tangible reminder of the separation between the urban community in Charlotte and Mecklenburg County’s surrounding rural farming communities during the early twentieth century.

- 3) The Mecklenburg County Courthouse was designed by noted Charlotte architect Louis H. Asbury.

- 4) The Neoclassical design of the Mecklenburg County Courthouse, a popular choice for public buildings during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, served as a fitting symbol of government authority, civic pride and cultural progress in center city Charlotte.

- 5) The Mecklenburg County Courthouse, along with its neighbor, C. C. Hook’s City Hall building, is among the last of center city Charlotte’s historic public buildings and retains almost all of its original exterior design features.

8. Integrity of design, setting, workmanship, materials, feeling, and/or association: The Committee judges that the architectural description prepared by Emily D. Ramsey indicates that the Mecklenburg County Courthouse meets this criterion.

- Ad Valorem Tax Appraisal: The Commission is aware that designation would allow the owner to apply for an automatic deferral of 50% of the Ad Valorem taxes on all or any portion of the property which becomes a designated “historic landmark.” The current estimated value of the building is $6,241,150. The total estimated value of the 7.072 acres (which also houses two other government buildings, including the recently completed new courthouse and jail) is 9,241,690.

Date of Preparation of this Report:

May 22, 2001

Prepared By:

Emily D. Ramsey

745 Georgia Trail

Lincolnton, NC

Statement of Significance

The Mecklenburg County Courthouse

700 East Trade Street

Charlotte, NC

Summary

The Mecklenburg County Courthouse, erected in 1928, is a structure that possesses local historic significance as a reflection of Charlotte-Mecklenburg’s tremendous economic and physical growth during the New South era of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries while serving as a tangible reminder of the physical and ideological separations that existed between the urban community in Charlotte and the rural farming communities that surrounded the city. By the 1920s, Charlotte had emerged as the center of a large and profitable textile region that stretched over a large portion of the South, while building “a diversified economic base” that included “banking, power generation and wholesaling.”1 The corresponding boom in population that followed gave Charlotte the edge over other Carolina cities, and in 1910 Charlotte overtook Wilmington to become the largest city in North Carolina. By the early 1920s, Charlotte citizens began a campaign for a new courthouse and city hall to meet the growing demands of city and county government and to reflect Charlotte’s new status.

Although the city of Charlotte was developing economically, commercially and culturally into one of the most important urban centers in the Carolinas, the rest of Mecklenburg County remained largely rural, dotted by small farming communities that resisted the changes occurring in Charlotte – changes that heralded the county’s shift from an agrarian economy to a manufacturing and commercial economy. The controversy over a proposed new courthouse and city hall complex in the 1920s, which ultimately resulted in the construction of C.C. Hook’s City Hall Building and a separate Mecklenburg County Courthouse, brought the tensions between Charlotte’s urban population and the county’s rural communities to the surface in heated public debate, and highlighted the ideological and practical divisions that separated Charlotteans from area farmers.

Architecturally, the Mecklenburg County Courthouse is significant as a well-preserved example of the Neoclassical style of architecture, a popular choice for public buildings in the late-nineteenth and early twentieth century. The building was designed by regionally important architect Louis H. Asbury, whose works include the H. M. McAden House and the Myers Park United Methodist Church in Myers Park, the Rudolph Scott House in Dilworth, and the William L. Bruns House in Elizabeth, among many others. Asbury’s design of the Mecklenburg County Courthouse, with its imposing rows of Corinthian columns and pilasters supporting a massive classical entablature, was a fitting illustration of Charlotte-Mecklenburg’s recent progress and a powerful symbol of governmental authority. The courthouse, along with its neighboring public edifice, C. C. Hook’s City Hall building, remains an integral part of Charlotte’s center city built environment and one of the few public buildings remaining from the city’s 1920s building boom.

Historical Background Statement

The late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century proved to be a time of tremendous growth and development for Charlotte-Mecklenburg. Charlotte, a rising star among New South cities, had become, by the early 1920s, the center of a large textile region that stretched from Georgia through South Carolina and west through Tennessee. Unlike many textile centers, however, Charlotte had also fostered a diverse economic foundation that included banking, wholesaling, and power generation as well as textile manufacturing. The city was attracting new businesses and residents at such as rapid rate that, by 1910, it had surpassed Wilmington in population to become the largest city in North Carolina. This distinction served to highlight Charlotte’s progress during the New South era. Charlotteans responded to the economic success of the 1910s and 1920s by beginning a building boom that would last until the Stock Market Crash of 1929 and the subsequent Great Depression of the 1930s. “Large portions of Charlotte,” writes historian Thomas Hanchett, “date from this period of prosperity” – Charlotte’s center city landscape in particular benefited from the economic boom and newly attracted businesses. A slew of new buildings rose along Tryon Street, including the ten–story Hotel Charlotte and the sixteen-story Johnson Building in 1924, topped by the twenty-story First National Bank tower in 1926. The Wilder Building, also erected in 1926, was followed by the opening of a branch of the Federal Reserve in 1927. The following year, Charlotte expanded its boundaries by almost twenty square miles.

In the midst of such frenzied construction and expansion, a local government building controversy raged. The debate centered around a proposal, first suggested by The Charlotte Observer and taken up by the Charlotte Chamber of Commerce in 1922, to erect a single public building that would serve as Charlotte’s city hall and the county courthouse, thus taking the place of the former City Hall at 5th and N. Tryon Streets and the existing Mecklenburg County Courthouse building at the corner of 3rd Street and South Tryon. The concept of a City-County Municipal building appealed to many Charlotteans, who took the view of prominent local attorney D. E. Henderson, proclaiming, “ . . . we are acting for the city of Charlotte and . . . for the county of Mecklenburg. That which is good for one is good for both.”2 The county population, consisting largely of farmers and rural workers, felt very differently. Supported by the Charlotte Mayor and the City Council, who lead the minority of the city’s dissenting vote, they succeeded in defeating the proposition by a two-to-one margin. Although supporters of the proposition were enraged that the vote was decided by those who would rather spend the day “picking cow ticks and boll weevils,” they were soon placated by the city’s rapid advancement of plans for a new City Hall.3 The building, designed by prominent local architect C. C. Hook, was completed in 1923. With the City Council now housed in a fine, spacious structure on East Trade Street, the Board of County Commissioner felt the pressure to upgrade their facilities intensify.

The 1925 debate over the county courthouse reflected, as the proposition of a City-County Municipal building had just two years before, the differences that existed between the rural citizens of Mecklenburg County and the city dwellers in Charlotte. Proponents of a new courthouse building, led by prominent Charlotteans who saw the courthouse as a symbol of the city’s progress and development in the New South era, insisted that the new structure be placed next to the City Hall building on Trade Street, thus creating a single governmental complex. Opponents, largely represented by Mecklenburg’s small farming communities, insisted that the existing courthouse building on South Tryon Street could be adequately expanded, and that the logical place for the Mecklenburg County Courthouse was Tryon Street, the “all-time center of the City,” where all but one of the previous courthouses had stood.4 Supporters and opponents of the new courthouse building and its proposed East Trade Street location voiced their arguments at two separate public hearings. On November 30, 1925, the Board of County Commissioners listened to speeches decrying the proposed new courthouse. John P. Hunter, magistrate for the Mallard Creek Township, voiced the concerns of Mecklenburg’s “country people.” The county’s rural population, Hunter argued, consisting of farmers who rarely ventured into the city and who relied on the familiar Tryon Street location, would never be able find the new courthouse if it were placed on East Trade Street, far from the center-city square. If the Board insisted on pursuing the new location, Hunter declared, officials would have to “place a big sign at the square showing the rural people how to reach it.”5

Mecklenburg County’s farming communities found an unlikely ally in the lawyers of Charlotte. A majority of the city’s lawyers also opposed the new courthouse – the proposed East Trade Street location would prove to be a major inconvenience for attorneys, most of whom worked out of the Lawyers Building (itself less than twenty years old) on South Tryon Street. Several lawyers, including W. C. Dowd, Sr. and A. R. Justice, spoke out against the new courthouse during the hearing, insisting that the existing courthouse could “provide enough space for adequate facilities for one thousand years.”6

Five days later, on December 5, 1925, proponents of the new courthouse turned out in record numbers (thanks in large part to the efforts of the Charlotte Woman’s Club) to advance the position of many of Charlotte’s leading New South citizens, who saw the courthouse as a symbol of the city’s recent progress and a reflection of its new status as the largest city in the state. Judge Wade W. Williams asserted that the County Commissioners had an obligation to follow “the urge and surge of present day progress and development” by building a new courthouse. The Charlotte Woman’s Club argued that the new courthouse building would benefit both city and county citizens by providing space for local organization meetings, agricultural workshops, and a produce market. All at the hearing maintained that the courthouse was a long overdue addition to the city landscape, and would be “in keeping with the dignity of the County.”7

In the end, the new courthouse’s urban supporters proved more convincing than its rural opponents. On December 7, 1925, the Board of County Commissioners voted unanimously to construct a new courthouse on East Trade Street. As with the new City Hall, the courthouse project, once decided, moved forward quickly. Within a month of the final vote, the Board commissioned Charlotte-native architect Louis H. Asbury to design the building. Asbury’s plans for the building were approved by the Board in May of 1926, and Charlotte-based contractor J. J. McDevitt Company was awarded the general construction contract in June. The $1,250,000 Neoclassical courthouse building was completed by January of 1928, and formally and extravagantly dedicated on March 10 of that year. County officials and members of the Board of County Commissioners greeted curious citizens, including many one-time opponents of the new building, as they toured the courthouses, offices, meeting rooms, and the rooftop jail, which The Charlotte Observer reported was “the most popular part of the courthouse,” which “every caller was anxious to visit.”8

Asbury’s Mecklenburg County Courthouse served as the main courthouse building until 1977, when a new courthouse building, designed by Charlotte architect Harry Wolf, was constructed at 800 East 4th Street.9 During the 1970s and 1980s, the area bordered by 3rd and East Trade Streets became a center for government and court buildings, including the 1989 14-story Charlotte-Mecklenburg Government Center, a civil courts building, a criminal courts building, and an underground intake center (now the Mecklenburg County Sheriff’s Office) adjacent to the Mecklenburg County Jail at 801 East 4th Street. In the late 1980s the area was officially named the Mecklenburg County Courthouse Complex – the 1928 Mecklenburg County Courthouse Building, renamed the Mecklenburg County Courthouse Annex in 1977, once again became the official Mecklenburg County Courthouse building.10 The 1928 Mecklenburg County Courthouse continues to serve as offices for Mecklenburg County but not for the courts.

Architectural Description and Contextual Statement

The Mecklenburg County Courthouse is locally significant as an excellently preserved example of the Neoclassical style of architecture and as a representation of the changing styles of architecture in the early twentieth century “The 1900s and 1910s,” Thomas Hanchett states, “saw a revolution in architectural taste” in Charlotte and across the United States. The Victorian aesthetic, with its “complex decoration, eclectic combinations, colors, shapes, and historical motifs,” was overshadowed by a resurgence in the clean lines and simple forms of the Colonial Revival, the Bungalow, and the Neoclassical styles.11 The Neoclassical style became particularly popular for government, commercial and institutional buildings. It provided a clean break from the lighthearted Victorian style, while still conforming to the fundamentally conservative “political, social, and economic thinking of Charlotte’s business elite.”12

During the early 1900s, professional architects, attracted by the city’s wealth and its citizen’s eagerness to build in the new styles, began bringing their firms to Charlotte for the first time. Louis H. Asbury was one such architect. A Charlotte-native, Asbury received formal degrees from both Duke University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. After graduation, he traveled abroad for over a year, studying European architectural masterpieces and deriving first-hand experience with classical architectural styles. When he returned to Charlotte in the 1910s to set up his first practice, Asbury arrived with the distinction of being one of the first formally trained architects in North Carolina and the first North Carolina member of the American Institute of Architects – he quickly became a well-known name as a residential, commercial, and civic architect with a diverse array of influences and fluent in a variety of architectural styles.13 By the time the Mecklenburg County Board of Commissioners began their search for an architect to design the new courthouse at East Trade Street, Louis Asbury had designed the several houses in Myers Park, Dilworth, and Elizabeth, as well as the Mt. Carmel Baptist Church and the Morgan School in the Cherry Neighborhood. In 1926, the Board of Commissioners awarded the contract for the new courthouse building to Asbury.

Louis Asbury designed the Mecklenburg County Courthouse in the Neoclassical Style – a uniquely American style using the classical elements from the baroque Beaux-Arts style distilled to their most basic essence. The clean lines, simple ornamentation, and timeless beauty of Neoclassical architecture made it a popular choice for public and civic buildings in the early decades of the twentieth century, and Asbury’s decision to build the Mecklenburg County Courthouse in the Neoclassical style was a logical one. Several of Charlotte’s most impressive public buildings, such as the Charlotte Post Office (now the Charles R. Jonas Federal Building) on West Trade Street, built in 1917 and expanded in 1934, and the Johnston Building, the Charlotte National Bank, the First National Bank, and Hotel Charlotte – all of which were built in the flurry of building activity that characterized the 1920s in center-city Charlotte – utilized the Neoclassical style.14

The Mecklenburg County Courthouse is an imposing three-story, rectangular limestone building, topped with a recessed structure that served as the county’s jailhouse until the 1960s and supported by a foundation fashioned from locally quarried granite. The building is set on a large, manicured plot of land, fronted by mature gingko and Southern magnolia trees. The façade of the building, facing East Trade Street, is dominated by a shallow recessed portico supported by ten massive fluted Corinthian columns and accessed by a broad granite stairway that spans the entire length of the portico. The façade features regularly punctuated fenestration – the third floor windows are original arched multi-paned windows, while the smaller, more modest openings on the first floor, second floor, and basement level seem to be modern replacements. An elaborate Corinthian entablature, featuring a delicate dentil mold, egg and dart detailing and modillion brackets, encircles the entire top perimeter of the building and is topped with a recessed balustrade designed to mask equipment and ductwork housed on the rooftop. Three pairs of original paneled bronze doors, set in stone encased openings spaced evenly under the façade’s central portico, form the Courthouse’s impressive main entranceway. Egg and dart molding along the edge of the doors mimics the detailing in the building’s entablature. A transom window with original patterned cast iron grills and large stone pediment crown each of the main doorways. The building’s side elevations feature secondary entrances sheltered by flat roof porches supported by Doric columns – the original glass and bronze doors and transom windows (which mimic the main entrance) remain on both elevations. The side elevations also feature original arched windows similar to those on the facade. The rear elevation, facing 4th Street, was designed by Asbury to be nearly as monumental and impressive as the Courthouse’s façade. A slightly smaller portico, supported by four Corinthian columns, forms the center of the rear elevation. Large bays flanking the portico feature Corinthian pilasters alternating with vertical rows of windows. Simple, relatively unadorned wings project from each end of the rear elevation.

| Louis Asbury |

The interior of the building has been remodeled extensively over the past sixty years – the original courtrooms have been transformed into various offices, and the entire east wing on the first floor was given over in the early 1990s to the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Law and Government Library. Although the interior retains most of its original polished marble floors and high marble wainscoting, as well as the original wrought iron and marble staircases, the interior as it stands now bears little resemblance to Asbury’s plan. The courthouse’s once spacious courtrooms, which formed the heart of Asbury’s design, have been partitioned and extensively remodeled into small office spaces. The original plaster ceilings have been covered with dropped ceilings, which are themselves partially concealed by masses of large ductwork, painted white. The first floor east wing and west wings are partitioned by clear glass walls and clear glass doors, and thus are still clearly visible from the middle of the hall. The second and third floors have been extensively altered to accommodate the Mecklenburg County District Attorney’s office. One of the most impressive spaces inside the Courthouse, the rooftop jail (considered at the time to be a masterful solution to the concerns of nearby residents), is now, according to Building Superintendent Roger Ellison, used mainly for storage. The second story of the jail space is the only well-preserved area of the building.

Despite the fact that much of the decorative marble-work and details such as the wrought iron staircase balustrades remain, the interior of the Mecklenburg County Courthouse as a whole has lost much of its original integrity, and should not be considered for designation.

Within the past two decades, many of center city Charlotte’s most impressive historic structures have been demolished. Little evidence remains of the building boom that transformed the city’s built environment in the 1920s. Such structures as the Johnson Building and Hotel Charlotte no longer grace the Charlotte skyline. The Mecklenburg County Courthouse, along with its neighbor, C. C. Hook’s City Hall Building, remain as an integral part of the center city landscape and a tangible reminder of Charlotte’s progress and development as a leading New South city in the early 1920s.

- Thomas Hanchett, “The Growth of Charlotte: A History” (Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission), p. 15.

- “Report on the Mecklenburg County Courthouse” (Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission, 1977), p. 2.

- The Charlotte Observer, July 29, 1923, p.1.

- “Report on the Mecklenburg County Courthouse,” p. 4.

- Minute Book 1916-1925 of the Board of County Commissioner of Mecklenburg County, p. 349-544.

- Ibid.

- “Report on the Mecklenburg County Courthouse,” p. 4.

- The Charlotte Observer, March 11, 1928, p.1.

- Lew Powell, “The Courthouse That Sis Built: All Consuming Renovation Plans Strain Committee,” The Charlotte Observer, March 24, 1988, p. 6C. Gary Wright, “The Courthouse? You Can’t Miss Them,” The Charlotte Observer, May 24, 1988, p. 1C.

- Ibid.

- Thomas Hanchett, “Charlotte Architecture: Design Through Time,” (Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission).

- Dr. Dan L. Morrill, “Survey and Research Report for the Textile Mill Supply Company Building” (Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission, 1998), p.5.

- Jack A. Boyte, “Architectural Description of the Mecklenburg County Courthouse” (Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission, 1977), p. 2.

- Hanchett, “The Growth of Charlotte,” p. 15-16.