The Agriculture Education Building at Long Creek Elementary School

The Agriculture Education Building at Huntersville Elementary School

This report was written on November 22, 1991

1. Name and location of the property: The property known as the Agriculture Education Building at Long Creek Elementary School is located at 9213 Beatties Ford Road in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina. The property known as the Agriculture Education Building at Huntersville Elementary School is located at 504 Gilead Road, Huntersville, Mecklenburg County, North Carolina.

2. Name, address and telephone number of the present owner of the properties: The owner of the properties is:

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education

Education Center, 701 East Second Street

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

Telephone: (704) 379-7000

Long Creek Elementary School Tax Parcel Number: 023-063-11

Huntersville Elementary School Tax Parcel Number: 017-121-13

3. Representative photographs of the property: This report contains representative photographs of the property.

4. A map depicting the location of the property: This report contains maps which depict the location of the property.

5. Current Deed Book Reference to the property: The most recent deed to the Huntersville Elementary School Tax Parcel Number 017-121-13 is listed in Mecklenburg County Deed Book 1653 at page 91. The most recent deed to the Long Creek Elementary School Tax Parcel Number 023-063-11 is not listed in the tax record.

6. A brief historical sketch of the property: This report contains a brief historical sketch of the property prepared by Ms. Paula M. Stathakis.

7. A brief architectural description of the property: This report contains a brief architectural description of the property prepared by Ms. Nora M. Black.

8. Documentation of why and in what ways the property meets criteria for designation set forth in N.C.G.S. 160A-400.5:

a. Special significance in terms of its history, architecture, and /or cultural importance: The Commission judges that the properties known as the Agriculture Education Buildings at Long Creek Elementary School and Huntersville Elementary School do possess special significance in terms of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County. The Commission bases its judgment on the following considerations: 1) the Agriculture Education Buildings were constructed in 1938; 2) most early Mecklenburg County residents were engaged in agriculture as a livelihood; 3) the Agriculture Education Buildings housed vocation courses to provide a practical education about crops, livestock and home manufacture for young men of high school age; 4) the Agriculture Education Buildings are architecturally significant as examples of buildings funded by the Public Works Administration (PWA) as part of the “New Deal” era to spur economic recovery; 5) the buildings still house modern day students providing valuable classroom space; and 6) the Agriculture Education Buildings provide the last link on each campus to an earlier school system before school consolidation and grade separation by school in Mecklenburg County.

b. Integrity of design, workmanship materials, feeling, and/or association: The Commission contends that the architectural description by Ms. Nora M. Black included in this report demonstrates that the Agriculture Education Buildings at Long Creek Elementary School and Huntersville Elementary School meet this criterion.

9. Ad Valorem Tax Appraisal: The Commission is aware that designation would allow the owner to apply for an automatic deferral of 50% of the Ad Valorem taxes on all or any portion of the property which becomes a designated “historic landmark.” Both of these buildings, however, are tax-exempt. The current appraised value of the Long Creek Agriculture Education Building (improvement only) is $58,380. The current appraised value of the Huntersville Agriculture Education Building (improvement only) is $84,280. The Long Creek Elementary School property is zoned RI 5. The Huntersville Elementary School property is zoned RS.

Date of Preparation of this Report: November 22, 1991

Prepared by:

Dr. Dan L. Morrill

in conjunction with

Ms. Nora M. Black

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission

1225 South Caldwell Street, Box D

Charlotte, North Carolina 28203

Telephone: 704/376-9115

Agriculture Education Buildings: Huntersville Elementary School and Long Creek Elementary School

by

P.M. Stathakis

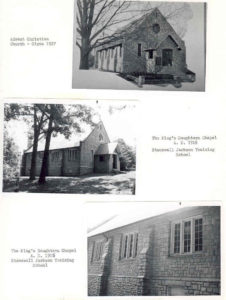

The Agricultural Education buildings (“Ag” buildings) at Huntersville and Long Creek Elementary Schools were both built in 1938. 1 The construction of these buildings was apparently funded by the Public Works Administration (PWA), a component of the National Industrial Recovery Administration (NIRA), one of the New Deal agencies created by Franklin Delano Roosevelt during the first “One Hundred Days” of his first presidential term.2 Plans for the building at Long Creek Elementary are available at the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools Physical Facility; the plans for the Huntersville building are lost.

The “Ag” Building at Long Creek Elementary is one of the oldest structures on campus. It is pre-dated only by the Boiler Room (1923) and the Gymnasium (1932). The “Ag” Building cost $11,000.00 to build. The Agriculture Education Building at Huntersville Elementary is the oldest extant building on its campus, a site which has been home to the Huntersville High School Academy, Huntersville High School and Huntersville Elementary School. Both of these “Ag” Buildings, now located at elementary schools, were originally part of high school campuses.

The high school for Huntersville moved from its original site to the North Mecklenburg High School campus in 1950. Up until that time, classes in agriculture and shop were taught in the old “Ag” Building by Arthur Meachum. Orland Gabriel taught agriculture and shop classes at Long Creek High School until 1951 when the high school was also moved to North Mecklenburg High School.

Vocational and Agricultural courses were introduced into the high school curriculum in the late 1920s. The students who took these courses were from rural families; many of them were from farm families. Former instructor Orland Gabriel believes that 85%-90% of the boys at Long Creek High School enrolled in his classes. These classes were optional; however, the consistently high enrollment suggests that these courses were not merely popular but necessary.4

In Agriculture classes, boys learned about field crops, and animal husbandry. Their education took advantage of the new technology available to farmers, particularly in horticulture and farm machinery. The students learned which variety of staple crop grew best in this region and what kind of mechanized equipment could help them farm efficiently. They also learned about the breeding, growth, and feeding of livestock. For the classroom segment of agriculture and shop classes, text book sets were available on field crops, animal industry, and shop projects.5

Part of the “Ag” students’ education took place outside of the classroom. The boys frequently went on field trips to neighboring farms to assist farmers with dehorning cattle, canonizing chickens, castrating cattle, swine, and sheep, and docking sheep. Cattle were dehorned to protect the herd and the farmer from being gored; the horns were removed with a large pair of pincers. Sheep had to have their tails shortened, or docked, for sanitary purposes. No anesthetics were used on the animals for these procedures; anesthesia was performed only by veterinarians, and the animals seemed to recover from these ordeals within thirty minutes. The students did have to catch the animals, and tie them up to prevent their escape and the likelihood of injury to those on the verge of removing various body parts from the captive livestock. Mrs. Orland Gabriel recalls that her husband often came home from these outings with his overalls and face covered with blood from a dehorning exercise.

In shop, boys learned to make such practical items as bookcases, corner cabinets, kitchen cabinets, and “whatnots” (small wall shelves used to display household items). Larger community-oriented projects included calf shelters for dairy farmers, and picnic tables. Most of the instruction in shop revolved around wood working, but the boys learned some metal work as well. Welding was a useful skill to know, and students often repaired items that required welding for area farmers or from their own homes in the school shops.

During the depression, the Long Creek “Ag” students ran a cannery as part of the curriculum for practical education and as a service to the surrounding community. The canning was not done in the “Ag” Building. Individuals who used the canning facilities at Long Creek High School paid a small fee to cover the expenses of cans and coal.8

The purpose of the vocation courses taught in the Ag buildings was to provide a practical education about crops, livestock, and home manufacture for young men who grew up in agricultural communities and who would probably inherit and work the family farm. The scientific management of domestic occupations was popular in the modern school curriculum, and such classes were not restricted to young men. The practical education for females, Home Economics, taught girls how to effectively run the household just as Agricultural and Industrial classes taught boys how to run a farm. Both of these curricula were aimed at self-sufficiency.9

The students involved in these classes not only learned skills that would help them as farmers; they also made regular contributions of their skills to the surrounding area. Their field trips, repair services, and large woodshop construction projects gave them practical experience, and at the same time assisted farmers who needed extra hands at critical times of the year to take care of livestock or crops. Agricultural education was offered in Mecklenburg County through the late 1970s.10

Both buildings have been in continuous use, even though Agriculture and Shop classes are no longer taught on these campuses. Huntersville Elementary uses the “Ag” Building as a Fine Arts Center. Long Creek uses its “Ag” Building for Academically Gifted classes. Both schools also use their “Ag” Buildings as centers for computer education, the practical curriculum of our times.

1 Records of Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, Bank Street Physical Facility. The plans were drawn in 1934 for the building at Long Creek. Interview with Charles Allison, 10-14-91.

2 The Public Works Administration was created to put people to work on public buildings and in flood control.

3 Interview with Bill Presson, Principal of Huntersville Elementary School and former Principal of Long Creek Elementary School.

4 Interview, Orland Gabriel. Mr. Gabriel was educated at North Carolina State University.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid. Less dramatic field exercises included pruning fruit trees and digging irrigation terraces.

7 Ibid.

8 Bill Presson and Orland Gabriel.

9 By the 1920s, education was compulsory for everyone seven to fourteen years old. Once an education was available to the masses, the traditional university preparatory curriculum (Greek, Latin, mathematics, literature, grammar, astronomy) was impractical for everyone. Education in how to manage a farm or household became an important and necessary element of the high school curriculum for those students who were not college bound. See: Edgar T. Thompson, Agricultural Mecklenburg and Industrial Charlotte: Social and Economic (Published by the Charlotte Chamber of Commerce, 1926), p. 101,115.; Legette Blythe, “Flames Take Huntersville Education Landmark” Charlotte Observer February 24, 1929, p. 9.

10 Orland Gabriel. After Long Creek High School was consolidated into North Mecklenburg High School, the “Ag” students at North Mecklenburg organized “Ag Day”. This day was devoted mostly to displays of farm machinery, and students from surrounding schools came to participate. North Mecklenburg also sponsored Hog Killing Day on which a slaughtered hog was brought to school and a representatives from a local abattoir came to school to demonstrate how to butcher slaughtered animals.

Architectural Sketches: Agriculture Education Buildings Located at Long Creek Elementary School and Huntersville Elementary School

Prepared by:

Ms. Nora M. Black

The Agriculture Education Buildings, located at Long Creek Elementary School and Huntersville Elementary School, are similar in appearance as well as original function. Both buildings are constructed of brick and feature an upper story set over a raised daylight basement. The windows have square cornerblocks and sills of cast limestone. The exterior of each building is belted between the daylight basement and the first floor with a soldier course of brick. To provide ample light, all sides of both buildings are pierced with large window openings to hold single, double, or triple sets of 6 / 6 double hung wooden sash. Each building has a low hipped roof covered with asphalt composition shingles. The front entries have small covered porches and double doors. Interiors of both Agriculture Education Buildings are constructed with two classrooms on the first floor and separate rest rooms for males and females on either side of the first floor entry foyer. The daylight basement of each building contains two classrooms, storage closets, and some physical plant space.

Long Creek Agriculture Education Building

The twenty-two acre campus of the Long Creek Elementary School is located at 9213 Beatties Ford Road at the intersection of Midas Springs Road. The Long Creek Agriculture Education Building is located on the southeast corner of the campus; the east wall of the building is parallel with Beatties Ford Road. The front of the Long Creek Agriculture Education Building, which faces north, is five bays wide. The center bay is dominated by a small hipped roof porch supported by white wooden piers set on a porch balustrade of brick. The solid double doors are painted blue. A wooden half-ellipse above the doors and all the building’s trim are white. The fourteen concrete steps leading to the porch landing have a white pipe railing. On the upper story, there are four windows; each is a 6/6 double hung wooden sash. The north facade of the daylight basement has two windows. One is a six-pane fixed sash; the other has an infill of wood with a center vent. A small brick room has been added at ground level on the west side of the entry porch. This one story addition houses a gas furnace. The access door is on the north side of the room; a vent pipe emerges from the roof and snakes around the Agriculture Education Building’s overhang.

The east and west sides of the building are roughly identical. Both sides are divided into three bays. The northern bay has a single window on each level; the other two bays have groups of three windows on each level. On the west side of the building, a single window air conditioning unit has been installed in the top half of a window in the center bay. On the east side, a window air conditioning unit has been installed in the rear or southernmost bay on each level. The main difference seen in the sides is ground level. On the eastern side of the building, ground level is two to three feet below the window sills; ground level on the western side is at the cast stone sills. The back (southern) facade of the building is dominated by two black metal fire escapes with white pipe railings. Each fire escape begins at a door on the upper level set in the center of two windows. Each door has a transom light above. Directly below the doors on the upper level are doors to the raised daylight basement classrooms. These doors also have transom lights and are flanked by a single window. The two doors of the lower level are set in a well with steps to reach ground level.

The interior of the upper level has the original hardwood floor in the foyer. Carpet covers the hardwood floors in the classrooms. A dropped ceiling has been installed to improve heating efficiency; the original ceiling is still in place above. Five-panel wooden doors open from the foyer into the classrooms. A narrow staircase leads from the first floor down to the raised daylight basement level. The basement level has modern heating vents installed along the exterior exposed brick walls. Round steel columns support the floor above.

The Long Creek Agriculture Education Building has 4116 square feet according to the tax card. It has no decorative lintels over any of the windows; instead, the varied-colored face brick continues in running bond. The cast stone cornerblocks are placed outside the frames of the windows that they decorate. Each corner of the building has an engaged brick pilaster in running bond. The deeply recessed mortar joints lend shadow detail to the walls. The brick pilasters and the limestone cornerblocks are the only decoration for this utilitarian building.

Huntersville Agriculture Education Building

The thirty acre campus of the Huntersville Elementary School is located at 504 Gilead Road at the intersection of Sherwood Drive within the city limits of Huntersville. The Huntersville Agriculture Education Building is located on the east side of the campus; the front of the building faces Gilead Road. The front, which faces south, is three bays wide. The center bay is dominated by a large hipped roof porch supported by square white wooden columns with slanting sides; wide staircases flank the porch. The solid double doors are painted blue; the door surround has three sidelights with a lower wooden panel on each side. All the building’s trim is painted white. The concrete steps leading to the porch landing have a pipe railing painted white set behind the concrete coping of the brick balustrade. On the upper story, there are two groups of windows; each group consists of three 6 / 6 double hung wooden sash. The lower half of the windows has been painted white; this provides privacy for the rest rooms in which the windows are located. The south facade of the daylight basement has two windows. One is a six-pane fixed sash; the other has an infill of brick that does not match the rest of the building.

As with the Agriculture Education Building previously discussed, the east and west sides of the building are roughly identical. The southernmost bays on the first floor level have a single window. The upper level has two other bays with a group of three windows as well as a triple window area that has been covered with wood. The raised basement area has seven single 6/6 double hung sash on each side of the building. The exception is the southernmost window on the lower level of the west facade that has been replaced with a vent for the furnace room. The smokestack for the furnace exits the basement level near the vent and pierces the overhang of the building to rise above the roof.

The window and door arrangement of the back (northern) facade of the Huntersville Agriculture Education Building is asymmetrical. There is a single black metal fire escape exiting the western classroom on the first floor level; a metal awning extends over the landing. Two 6 / 6 double hung sash help provide light to the western classroom. The first floor level also has a group of three 6/6 double hung wooden sash providing light to the eastern classroom. Doors to the raised daylight basement classrooms are also covered with metal awnings. The westernmost door has a large awning that also covers an area beside the door that has an infill of new brick. Three small single windows are spaced unevenly between the two doors. The two doors of the lower level exit the basement at ground level. Air conditioning is provided to the classrooms by units located in windows on the north facade.

The interior of the Agriculture Education Building has a dropped ceiling to improve heating efficiency; the original ceiling is still in place above. Five-panel wooden doors are found on both levels of the buildings as well as flush doors for the storage closets. Windows and doors have surrounds of a single board trimmed with a narrow piece of molding. The entire southern end of the raised daylight basement level is separated from the classrooms by horizontal board walls to provide rooms for the physical plant and storage closets. The daylight basement level has interior walls of exposed brick and round steel columns that support the floor above.

The Huntersville Agriculture Education Building has 4032 square feet according to the tax card. The front door and all windows have lintels constructed of a soldier course of brick. The corner blocks of the openings are placed within the width of the door and window frames. The surface of the building is constructed of varied-colored face brick laid in running bond. Downspouts are placed randomly at corners of the building.

Conclusion

The Agriculture Education Buildings at Long Creek and Huntersville provide a solid architectural link to the era of the yeoman farmer in Mecklenburg County. The Neoclassical touches seen in these two utilitarian buildings show strong ideas of tradition expressed in educational facilities. Most of the original fabric is relatively unchanged and in very good condition; that may be a simple result of the need for space to house a growing student population. The importance of the two Agriculture Education Buildings, however, is reflected in the fact that they are still serving as functional, viable classrooms even after a revolution in Mecklenburg County — the revolution that swept citizens from cotton fields and hog killings to computers and bank mergers.