- Name and location of the property: The property known as the Long Creek Mill Ruin is located approximately 1,000 feet southeast of the intersection of Mt. Holly-Huntersville Road and Beatties Ford Road in northern Mecklenburg County.

- Name, address, and telephone number of the current owner of the property: Mecklenburg County

- Representative photographs of the property: This report contains representative photographs of the property.

- A map depicting the location of the property:

- Current Tax Parcel Reference and Deed to the property: The tax parcel numbers of the property are 02516106, 02516108. The most recent deeds for the property are recorded in Mecklenburg County Deed Books 08939 page 452, and 07165 page 291.

- A brief historical sketch of the property: This report contains a brief historical sketch of the property prepared by Stewart Gray.

- A brief architectural description of the property: This report contains a brief architectural description prepared by Stewart Gray.

- Documentation of why and in what ways the property meets the criteria for designation set forth in N.C.G.S 160A-400.5.

- Special significance in terms of its history, architecture and/or cultural importance: The Commission judges that the property known as the Long Creek Mill Ruin possesses special significance in terms of Charlotte-Mecklenburg. The Commission bases its judgment on the following considerations:

1) The Long Creek Mill Ruin is significant as the site of an earlier mill that was prominent in the Colonial era of Mecklenburg County.

2) The Long Creek Mill Ruin is significant in terms of the local community. The mill was a commercial, social, and civic center of the community during the 19th century. The mill was associated with prominent families associated with Hopewell Presbyterian Church and St. Mark’s Episcopal Church.

3) The Long Creek Mill, later known as Whitley’s Mill, was the last operating grist mill in north Mecklenburg.

4) As an abandoned commercial hub, the Long Creek Mill Ruin may possess significant archeological resources.

- Integrity of design, setting, workmanship, materials, feeling and/or association: The Commission contends that the architectural description prepared by Stewart Gray demonstrates that the property known as the Long Creek Mill Ruin meets this criterion.

- Ad Valorem Tax Appraisal: The Commission is aware that designation would allow the owner to apply for an automatic deferral of 50% of the Ad Valorem taxes on all or any portion of the property which becomes a “historic landmark.” The property is exempt from the payment of Ad Valorem Taxes.

- Portion of the Property Recommended for Designation: The land and all features associated with tax parcels 02516106 and 02516108.

Historical Essay

Long Creek Mill, ca. 1900

The Long Creek Mill was a grist mill built around 1820. Its ruin is located adjacent to Long Creek in northern Mecklenburg County, approximately 1,000 feet southeast of the intersection of Beatties Ford Road and Huntersville-Mt. Holly Road. The mill ruin consists of a stone foundation, stone walls that channeled water leaving the mill, and a remarkably intact millrace of about 1,000 feet in length. Remnants of the dam or dams are scattered along the creek, but topography would dictate that the dam, or dams, were located 320’ to 450’ due east of the mill ruin. The Long Creek Mill was the second mill built on the property. The property has also been known as the Long Creek Mills, Long Creek Mill Farm, and Whitley’s Mill. The first mill was built by Captain John Long sometime before the Revolutionary War. Long Creek is named for Long who was a Revolutionary War patriot. Long died in 1799 at age fifty-five and is buried in the Hopewell Cemetery. 1 His tracts along Long Creek were sold in 1804 and 1809. 2 Long’s mill was located about 150 yards upstream from the Long Creek Mill Ruin. 3

Long’s mill would have been a significant landmark in the colonial world of Mecklenburg County. Located on the Great Road (Beatties Ford Road) approximately nine miles north of the crossroads town of Charlotte, the mill would have served the settlers of the area as they transformed the backwoods frontier into agricultural land. Long’s mill likely would have been the only commercial institutions in the area. The ca. 1760 log Hopewell Church building (non-extant), located along the Great Road 1.5 miles to the north, and Long’s mill may have been the only non-farm buildings in the community’s landscape. While wheat and corn could be ground by hand or by hand or animal powered mills, a water powered mill operated by an experienced miller was much faster and more efficient. Other grist mills that operated in colonial-era Mecklenburg included the Park’s Mill, Mitchell’s Mill, and Tomas Polk’s mill in Charlotte. 4 The proliferation of grist mills throughout the backcountry demonstrates that the grist mills, even with a one-tenth payment going to the miller, were virtually essential for successful farming.

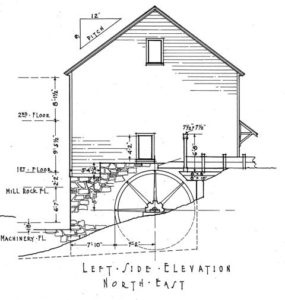

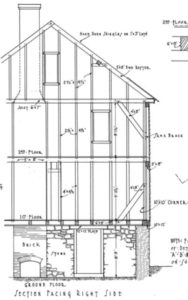

During the Revolutionary War Lord Charles Cornwallis was attracted to Charlotte and Mecklenburg County because the numerous mills along the county’s many creeks gave the promise of grain for his army. Indeed, Long’s Mill was the object of British troops advancing out of Charlotte up Beatties Ford Road in October 1780, when they were set upon by patriots at the McIntyre Farm in the skirmish known as the “Battle of the Hornets’ Nest.” 5 After Long’s death the land including Long’s mill and farm was acquired by Colonel John “Jacky” H. Davidson in 1815-1818. 6 In about 1820 Davidson replaced Long’s mill with the Long Creek Mill. 7 It is likely that Davidson used The Young Mill Wright and Miller’s Guide. The technical manual was written by Oliver Evans of Newport Delaware in 1795 and was updated in fifteen editions. 8 It was sold widely in America and revolutionized milling by separating and fully mechanizing the different functions of the mill on separate floors. 9 Davidson’s Mill was built during the height of the book’s popularity, and the tall Long Creek Mill resembled illustrations in the book.

|

|

|

| The illustration (left) from The Young Mill Wright resembles the drawings of the Long Creek Mill (center and right) | ||

It is known that the builder of the Torance Mill (1825 and rebuilt in 1844) located a few miles north of the Long Creek Mill used The Young Mill Wright and Miller’s Guide to design that mill. One remarkable element of the Long Creek Mill is the nearly 1,000’ millrace that extends roughly east from the mill site. It is possible that Davidson reused the dam from Long’s mill which may have been more than 450’ upstream. Also, The Young Mill Wright and Miller’s Guide recommends long mill races. The long mill race and separation from the dam supposedly protected the mill from being washed away during flooding. The long mill race may also have mechanical advantages in terms of capacity and consistent flow. 10

In his history of the Hopewell Community written in 1907, J. B. Alexander relates that before the Civil War the Long Creek Mill was a center of the community. Taxes were collected at the mill. Voting took place there with politicians literally speaking while standing on stumps. According to Alexander, political campaigning at the Long Creek Mill involved fighting, and “Whiskey, cider, watermelons, and ginger cakes,” being passed out. The mill was also the location of militia drills which Alexander described as “laughable burlesque.” 11

In 1835 Davidson moved to Maringo County, Alabama where he became very wealthy. Through an agent he sold his Long Creek property in 1838, and in 1839 the land including the “Grist Mill and dwelling house,” was purchased by Major John H. Caldwell. 12 Caldwell was apparently successful in business. A substantial farmer in northern Mecklenburg, he manufactured brick for the Davidson College campus buildings and for the federal mint building in Charlotte. Caldwell also contracted his slaves to work for the North Carolina Railroad. In 1860 Caldwell sold the property to Robert Davidson Whitley.

Robert Davidson “R. D.” Whitley was born in 1820 and was reared at Holly Bend, the plantation of Robert “Robin” Davidson. Robin Davidson was at one time the wealthiest planter in Mecklenburg County. Davidson owned nearly 3,000 acres and 109 slaves in Mecklenburg County in 1850, and he owned another plantation in Alabama. 13 R. D. Whitley’s mother, Jane Price Whitley, was Robin Davidson’s niece. At some point, Whitley and his mother moved to Alabama. They returned to North Carolina, and in 1860 R. D. Whitley purchased the land containing the Long Creek Mill. 14 We do not know if R. D. Whitley made any significant changes to the mill or to how the business was operated. It is likely that the mill, renamed Whitley’s Mill, continued to function as a center of the rural community. At some point in the nineteenth century a store was built across Long Creek from the mill and served as the area’s post office. 15 The Chas. Emerson & Co. Charlotte City Directory 1879-1880 gives the community around the mill the name “Martindale,” and lists R. D. Whitley as a farmer. 16 In addition to farming over 300 acres, and owning the mill and store, R. D. Whitley was active in real estate and is listed as grantee in over 30 conveyances before his death in 1900. 16 R. D. Whitley was also instrumental in the establishment of the nearby St. Mark’s Episcopal Church. In addition to helping to organize the church, Whitley and his wife Martha McCoy Whitley sold to the trustees some of the land for the sanctuary for a “modest sum,” and donated land for the rectory. 17

|

Long Creek Mill in operation ca.1915 |

When R. D. Whitley bought the mill in 1860, water powered milling was in its ascendancy with nearly 14,000 thousand mills operating in the country, most of them isolated country mills like the Whitley’s Mill, with a potential to produce up to 50 barrels of flour a day. 18 The world was very different when Joseph S. Whitley took over operation of the mill and store after his father’s death in 1900. Larger mills producing flour for the domestic market and for export, such as the massive 1915 Interstate Milling Company located in the Fourth Ward in Charlotte, began to dominate. Where there had been at least five grist mills operating in northern Mecklenburg in the nineteenth century, by 1918 the Whitley’s Mill was the only one still operating. The 1918 “Biennial Report of The North Carolina Department of Agriculture” lists just three mills in all of Mecklenburg County: the Interstate Milling Company, Charlotte; DA Henderson, Matthews; and Whitley Mill, Long Creek. Around 1919 the mill ceased to operate, perhaps due to a storm that damaged either the mill or the dam. 19 In 1927 the estate of R. D. Whitley was divided among his heirs. 20

In 1934 Whitley’s Mill was inventoried by the Historic American Buildings Survey. By that point the tall building was in decay with a notably sagging roof. The building was photographed and measured drawings were made. A 1938 U.S. Parks Service publication used the mill’s HABS photograph to illustrate the overall deterioration of the nation’s historic buildings. At some point after the survey work was completed, the metal waterwheel, gears and other machinery were removed. It is believed that the mill workings were reinstalled in a reproduction grist mill south of Charlotte by Dr. Charles D. Lucas around 1935. 22

Above: the ruined Lucas Mill in Charlotte with machinery that may have been removed from the Long Creek Mill around 1935.

- Lee Kemp Ramsey, “The Long Creek Settlement and the Gum Branch East of the Catawba River, Mecklenburg County, North Carolina: A Genealogical Survey of the Neighbors and Allied Families of William and Nancy Ramsey,” Mecklenburg County NC Geneology Project, accessed May 20, 2012, http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~ncmeckle/longcrk.htm

- Mecklenburg County Old Real Estate books/pages: 18-52 and 19-517

- J. B. Alexander, Biographical Sketches of the Early Settlers of the Hopewell Section (Charlotte: Observer Printing and Publishing House, 1897) 31.

- C. L. Hunter, Sketches of Western North Carolina, Historical and Biographical: Illustrating Principally the Revolutionary Period of Mecklenburg, Rowan, Lincoln, and Adjoining Counties, Accompanied with Miscellaneous Information, Much of it Never Before Published(Raleigh: Raleigh News Steam Job Print, 1877) 132, 137, 298.

- Dan L. Morrill, Historic Charlotte: An Illustrated History of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County (San Antonio: Historical Publishing Network, 2001) 13.

- Mecklenburg County deeds 20-103 and 19-56

- Alexander, p. 31.

- “Who Was Oliver Evans?” accessed on May 20, 2012 at http://www.greenbankmill.org/oliverevans.html.

- “Colvin Run Mill,”The Fairfax County Park Authority Division of History, Annandale, Virginia, accessed on May 20, 2012 at http://gfhs.org/local_lore/colvin_mill.htm.

- Dan L. Morrill, “Torrence Mill” (Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Properties Commission, 1978) accessed on May 20, 2012 at http://www.landmarkscommission.org/S&Rs%20Alphabetical%20Order/surveys&rtorrancemill.htm. Alexander p.31.

- Alexander, p. 31.

- Deed 25-192

- “Survey and Research Report on Holly Bend,” (Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Properties Commission, 1974?) accessed on May 20, 2012 at http://www.landmarkscommission.org/essays/HollyBend.html.

- Deed 4-386

- Interview by Stewart Gray with Brown D. Whitley, May 7, 2012.

- The Chas. Emerson & Co. Charlotte City Directory 1879-1880 (Charlotte: Charlotte Observer Steam Job Print, 1879) 138.

- Dan Morrill, “Survey and Research Report on the St. Mark’s Episcopal Church,” (Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission, 1983) accessed on May 20, 2012 at http://www.landmarkscommission.org/S&Rs%20Alphabetical%20Order/surveys&rstmarks.htm. Grantee Index to Real Estate Conveyances – Mecklenburg County, NC, p. 138-139

- St. Mark’s S&R

- Robert Lundegard, “Country and City Mills in Early American Flour Manufacture and Export.” Report for the Colvin Mill Historic Site, 2007.

- HABS Report on Whitley’s Mill, State Route 2074, Charlotte vicinity, Mecklenburg, NC, 1934. Also, Interview BR Whitley.

- Mecklenburg County Map Book 345.

- Interview by Stewart Gray with Dr. Dan L. Morrill, May 15, 2012.

Architectural Description

The Long Creek Mill Ruin is located on the north bank of Long Creek in northern Mecklenburg County. The mill ruin lays due east of Beatties Ford Road, approximately 375 feet from the edge of the pavement. Once open farm land, the area is covered with second-growth forest. The most substantial element of the mill ruin is the mill building’s stone foundation which sits only about ten feet from the north bank of the current channel of Long Creek. It is composed of rough-cut granite laid in irregular courses. The walls are approximately two foot thick. The foundation is nearly square, thirty-two feet wide by twenty-nine feet deep. The stone walls are broken in places, with only the northeast corner, built into the hillside, having retained its original height. Much of the stonework appears to have fallen inward into the foundation. The foundation was stepped with a ten foot tall section in the northeast corner. The remainder of the foundation walls were originally eight feet tall.

The land rises steeply to the north of the ruin and the northeast corner of the foundation is level with grade. The southwest corner of the foundation rises from the grade five feet, and the stone work is in good condition and not obscured by ruble. The southeast corner of the foundation is buttressed by an irregularly coursed rubble stone wall that extends toward the creek. This wall formed the western edge of a five-foot-wide discharge chute, or tailrace. The eastern wall of the tailrace is formed by a partially extant retaining wall of unshaped stones.

The building foundation is bordered on the east by a wheel pit. The wheel pit is relatively intact, perhaps because the stonework of the wheel pit was built into the hillside, as opposed to being freestanding stonework. The pit is five feet six inches wide. Ruble from the collapsed east wall of the foundation has partially filled the pit. Yet even with the ruble, the rear or north wall of the pit features approximately eight feet of exposed rock.

The red square is the location of the mill ruin. Long Creek is shown in blue. The approximately 1,000′ millrace is depicted in pink. Evidence of dams are shown in orange.

The millrace joined the mill at the northern edge of the wheel pit. The millrace was an elevated flume (no longer extant) where it joined the mill , but for most of its approximately 1,000 foot length, it is a channel. The existing channel width varies from six to ten feet wide, but because of erosion and sediment it is difficult to determine the original dimensions of the channel. Portions of the millrace channel are a simple ditch. Other sections of the millrace channel feature significant earthen retaining walls. Other sections of the millrace channel are lined with stones. Approximately 320 feet from the mill, the millrace shows evidence of a gate and a stone discharge flume. This gate may have allowed the millrace to be stopped or discharged back into the creek below the dam but before it reached the mill. The millrace has very little slope, dropping in elevation less than ten feet over its entire length.

Evidence of two dams is located along the creek in the form of rock piles and borings in the bedrock. One dam may have been located approximately 320 feet upstream from the mill ruin. Another possible site is located approximately 450 feet upstream of the mill ruin.

While the mill is a ruin, early-20th-century photographs of the mill exist, and measured plans for the mill were produced as part of the Historic American Building Survey (HABS) in 1934. The stone foundation was pierced by three small window opening on the south elevation and was topped with a side-gabled two-story frame building. The building was two bays wide and two bays deep. A brick chimney was located on the west elevation. The building incorporated heavy timber construction. The roof was covered with wooden shake. Aside from the stonework described above, no elements of the mill building appear to have survived. Other buildings such as a house and a store were once located near the mill. No prominent visible elements of these structures have survived.

.jpg)