THE VILLALONGA-ALEXANDER HOUSE

This report was written on June 4, 1978

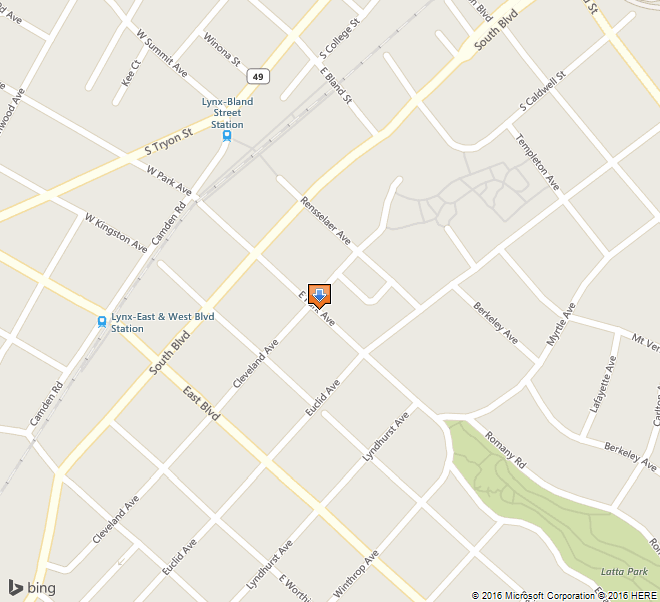

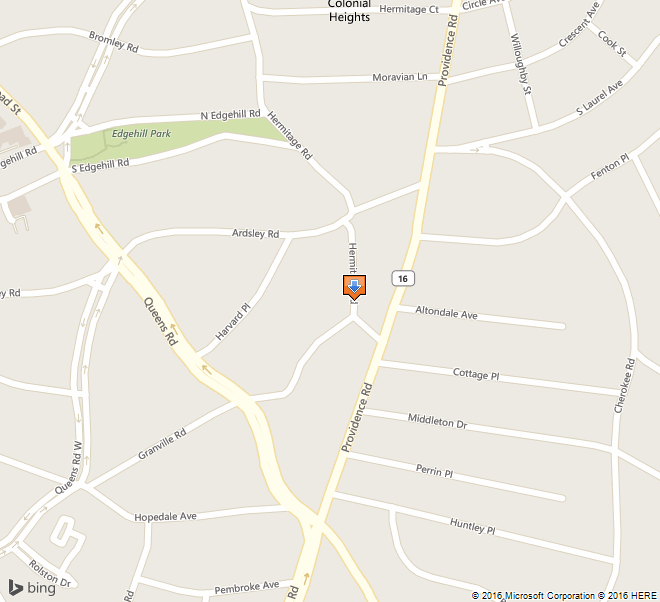

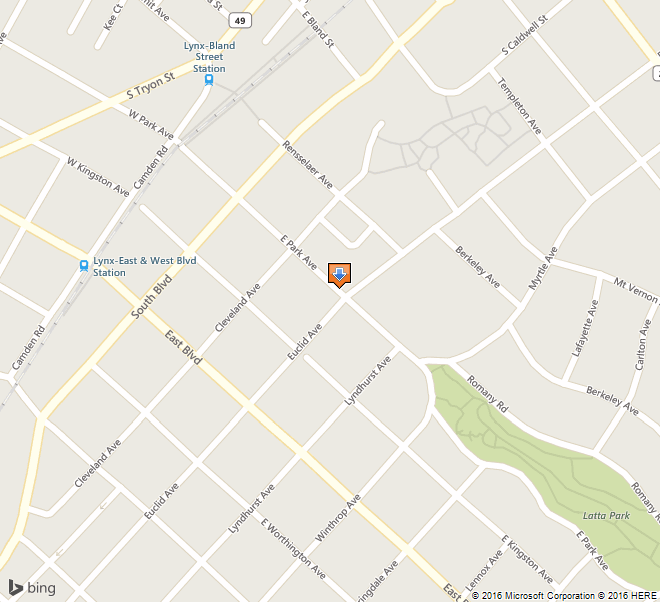

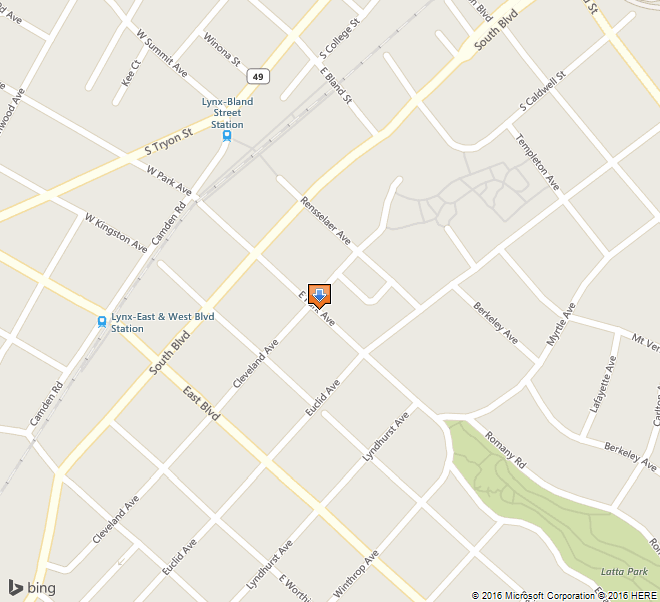

1. Name and location of the property: The property known as the Villalonga-Alexander House located at 301 E. Park Ave. in Charlotte, N.C.

2. Name, address and telephone number of the present owner and occupant of the property:

The present owner of the property is:

Mrs. Ouida Dasher Brown

301 E. Park Ave.

Charlotte, N.C. 28203

Telephone: 332-2234

The present occupants of the property are:

Mrs. Ouida Dasher Brown

Mrs. Inez Dasher

An aggregate of roomers

301 E. Park Ave.

Charlotte, N.C. 28203

Telephone: 332-2234

3. Representative photographs of the property: This report contains representative photographs of the property.

4. A map depicting the location of the property: This report contains a map depicting the location of the property.

5. Current Deed Book Reference to the Property: The most recent reference to this property is recorded in Mecklenburg County Deed Book 1625 at Page 180. The Tax Parcel Number of the property is 12307101.

6. A brief historical sketch of the property:

Mr. John L. Villalonga, president and treasurer of the Charlotte Roof and Paving Co. and president of the Charlotte Brick Co., began the construction of his residence in Dilworth in the summer of 1900.l A perusal of the local newspapers reveals that the edifice was regarded as one of the handsomest and most complete houses in Charlotte.”2 Indeed, The Charlotte Daily Observer of March 4, 1901, urged the public to visit the J. H. Wearn Co. for purposes of viewing and appreciating the “quartered oak doors” which Mr. George W. Farrington had made “for the new house of Mr. J. L. Villalonga.” The newspaper reported that the panels of the doors were fashioned from “the very finest grade of curly-quartered oak” and that the workmanship demonstrated “what North Carolina forest products and what Charlotte workmen” could accomplish.3 Mr. Villalonga and his wife, Constance M. Villalonga, moved into their home in late March or early April 1901.4 That Mr. and Mrs. Villalonga were active in community, affairs is certain. He was a member of the Vestry of St. Peter’s Episcopal Church, and she participated in the activities of the Saturday Afternoon Club, a prestigious womens organization of that era.6

In February, 1903, Mr. and Mrs. Villalonga sold their home in Dilworth and moved to New York City.7 The new owner was Robert O. Alexander, a native of Sampson County, N. C., who had most recently resided in Monroe, La., where he had been a cotton broker. He practiced the same profession in Charlotte for over twenty years and was regarded as one of the best authorities on staple cotton in the state.8 Mr. Alexander also acquired the reputation of being a deeply religious and pious individual. A self-proclaimed “sanctificationist ” and member of First Presbyterian Church, he conducted revival meetings in a tent on South Boulevard in September 1903. According to the Charlotte Daily Observer, he preached to “large congregations,” telling them that material prosperity would only come to those who believed as he did. “If you prefer to live on bacon and cornbread, Mr. Alexander proclaimed, keep on living as you are living now. But if you wish to have good fat beefsteak and biscuits and butter be sanctified as I am.”9

Regardless of how one feels about Mr. Alexander’s religious proclivities, one is forced to admit that he did prosper. In addition to being a successful cotton broker, he acquired and developed large tracts of land at Black Mountain, N. C. He was also largely responsible for the development of the Presbyterian Assembly Grounds at nearby Montreat.10 Mr. Alexander died on November 13, 1926, at the age of sixty-three,11 leaving behind a widow and several children.12 May Herndon Alexander, daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Edward Beverly Herndon, was born on July 1, 1876, in Shreveport, LA. It was her that she would meet and marry R. O. Alexander. She moved with her husband to Charlotte in 1901.13 One can imagine the excitement which Mrs. Alexander must have experienced when occupying her new home in February 1903. According to some sources, Mrs. Alexander had told her husband that she would be happy to live in North Carolina if she could reside in the house which Mr. J. L. Villalonga had erected in Dilworth. Local tradition holds that it was this news which prompted Mr. Alexander to purchase the structure.14 Of course, he always insisted that Divine Providence had played a part in the transection.15 A glimpse into the lavish social life which occurred in the Alexander’s new abode is provided by an article which appeared in the Charlotte Daily Observer on April 24, 1903. It described a reception which had taken place in the house the previous evening. The rooms, the article reported, were beautifully decorated, the color scheme of pink, white and green being exquisitely carried out in roses, carnations and smilax.” The newspaper went on to relate that palms were placed throughout the house and that “music was furnished by the Academy orchestra.” 16 Mrs. Alexander lived in the house until 1936, when the Federal Government foreclosed a mortgage which it held on the property. 17 She rented a room in an apartment house next door and continued to reside there until her death on May 10, 1958.18 Despite the urgings of the subsequent owners of the property, Mrs. Alexander never entered the home again. Apparently, her emotions would not allow her to do so. 19 Mrs. Alexander was survived by seven children, four daughters and three sons. They included Mrs. T. E. Hemby, Mrs. McAlister Carson, Mrs. Ruth A. Roberts, Mra. Phillip Hasel, Mr. E. Herndon Alexander, Mr. Robert O. Alexander, Jr. and Mr. John McKnitt Alexander. All had grown up in the home at 301 E. Park Ave.20

In 1938, the property was purchased by Julian E. Dasher and his two sisters, Doris and Ouida.21 They in turn granted a life estate in the property to their mother, Clara E. Dasher.22 The younger Dashers and their spouses resided in the house, and Clara Dasher began to rent rooms to boarders. This practice continued until May 21, 1953, when Mrs. Dasher expired.23 Ouida Dasher Brown and her husband, J. Arthur Brown, assumed the responsibility of managing the property. Mr. Brown, who was in the wholesale lumber business, died on August 24, 1964, at the age of seventy-seven. Mrs. Brown continues to reside in the structure and to rent rooms to boarders.24 The most dramatic event in the physical history of the Villalonga-Alexander House occurred on March 14, 1948. A fire destroyed the greater portion of the interior of the center of the structure, including the roof and dormers.25 “Fire gutted the old Alexander home at 301 East Park Avenue early yesterday morning,” the Charlotte Observer reported. “A stairway leading to the second floor,” the newspaper explained, “acted as a perfect draft, drawing the flames upward through the roof. The rear of the house wee damaged slightly by water.”26 The owners of the property were forced to live in a small house on Cleveland Ave. while extensive repairs were made to the main house. Financial considerations made restoration of the structure impossible. However, the owner did attempt to be sensitive in the changes and alterations which they were compelled to make.27

Footnotes:

1 Charlotte City Directory 1902, p. 460. The Charlotte Daily Observer (September 11, 1900) p. 5.

2 The Charlotte Daily Observer (February 3, 1903) p. 5.

3 The Charlotte Daily Observer (March 4, 1901) p. 6.

4 The Charlotte Daily Observer (March 10, 1901) p. 6.

5 The Charlotte Daily Observer (January 7, 1902) p. 5.

6 The Charlotte Daily Observer (November 6, 1901) p. 5.

7 Mecklenburg County Deed Book 174, p. 318. The Charlotte Daily Observer (February, 3, 1903) p. 5.

8 Mecklenburg County Death Book 26, p. 1036. The Charlotte Observer (November 14, 1926) sec. 1, p. 4.

9 The Charlotte Daily Observer (September 21, 1903) p. 5.

10 The Charlotte Daily Observer (November 14, 1926) sec. 1, p. 4.

11 Mecklenburg County Death Book 26, p. 1036.

12 The Charlotte Daily Observer (May 11, 1958) p. 15E.

13 Ibid.

14 The Charlotte News (March 15, 1948) p. 5A.

15 The Charlotte Daily Observer (September 21, 1903) p. 5.

16 The Charlotte Daily Observer (April 24, 1903) p. 5.

17 Mecklenburg County Deed Book 901, p. 154.

18 The Charlotte Observer (May 11, 1958) p. 15E.

19 Interview of Mrs. Ouida Dasher Brown by Dr. Dan L. Morrill (May 16, 1978). Hereafter cited as Interview.

20 The Charlotte Observer (May 11, 1958) p. 15E.

21 Mecklenburg County Deed Book 953, p. 67.

22 Mecklenburg County Deed Book 953, p. 66.

23 Interview

24 Ibid.

25 For a photograph of the structure immediately following the fire, see The Charlotte News (March 15, 1948) p. 5A.

26 The Charlotte Observer, (March 15, 1948) p. 1B.

27 Interview.

7. A brief architectural description of the property: This report contains an architectural description prepared by Ms. Ruth Little-Stokes, architectural historian.

8. Documentation of wky and in that ways the property, meets the criteria set forth in N. C. G. S. 160A-399.4:

a. Historical and cultural significance: The historical and cultural significance of the property known as the Villalonga-Alexander House rests upon three factors. First, it is an early example of Colonial Revival style architecture in the City of Charlotte. Second, it is one of the oldest mansions which survives in Dilworth, Charlotte’s initial streetcar suburb. Third, it has associative ties with individuals of local prominence.

b. Suitability for preservation and restoration: The structure and grounds are in an excellent state of repair. On balance, the house is well preserved, except for damage which resulted from the fire on March 14, 1948. Sufficient documentation exists to permit the restoration of the exterior of the structure.

c. Educational value: The Villalonga-Alexander House has educational value because of the historical and cultural significance of the property.

d. Cost of acquisition, restoration, maintenance or repair: At present, the Commission has no intention of securing the fee simple or any lesser included interest in this property. The Commission presently assumes that all costs associated with restoring and maintaining the property will be paid by the owner or subsequent owner of the property.

e. Possibilities for adaptive or alternative use of the property: The Villalonga-Alexander House is currently zoned for office use (O6 ). The Commission believes that the structure is best suited for residential use, either single or multi-family.

f. Appraised value: The Current tax appraisal of the improvements on the property is $710. The current tax appraisal of the .312 acres of land is $22,410. Tho most recent annual tax bill on the property was $388.42. The Commission is aware that designation would allow the owner to apply for a deferral of 50% of the Ad Valorem taxes on all or any portion of the property which becomes “historic property”.

g. The administrative and financial responsibility of any perrson or organization willing to underwrite all or a portion of such costs: As stated earlier, the Commission presently has no intention of purchasing the fee simple or any lesser included interest in this property. Furthermore, the Commission presently assumes that all costs associated with the property will be paid by the present or subsequent owners of the property.

9. Documentation of why and in what ways the Property meets the criteria established for inclusion in the National Resister of Historic Places: The Commission judges that the property known as the Villalonga-Alexander House does meet the criteria of the National Register of Historic Places. Basic to the Commission’s judgment is its knowledge that the National Register of Historic Places, established by the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, represents the decision of the Federal Government to expand its recognition of historic properties to include those of local, regional and State significance. The Commission believes that its investigation of the property known as the Villalonga-Alexander House demonstrates that the property possesses local historical and cultural importance. Consequently, the Commission Judges that the property known as the Villalonga-Alexander House does meet the criteria of the National Register of Historic Places.

10. Documentation of why and in what ways the property is of historical importance to Charlotte and/or Mecklenburg County: The property known as the Villalonga-Alexander House is historically important to Charlotte and Mecklenburg County for three reasons. First, it is an early example of Colonial Revival style architecture in the City of Charlotte. Second, it is one of the oldest mansions which survive in Dilworth, Charlotte’s initial streetcar suburb. Third, it has associative ties with individuals of local prominence.

Chain of Title

1. Mecklenburg County Deed Book 1625, Page 180 (August 7, 1953).

Grantors: Doria Dasher Henley & husband, John D. Henley Julian E. Dasher & wife, Florine Hallman Dasher, Alva Lee Dasher & wife, Inez Long Dasher

Grantees: Ouida Dasher Brown

2. Mecklenburg County Deed Book 953, Page 66 (July 22, 1938).

Grantors: Ouida D. Brown & husband J. Arthur Brown Doris Dasher Henley & husband, John D. Henley Julian E. Dasher & wife, Florine H. Dasher

Grantee: Clara E. Dasher (Life Estate)

3. Mecklenburg County Deed Book 953, Page 65 (July 22, 1938).

Grantor: Ouida D. Erown & husband, J. Arthur Brown Doris Dasher Henley & husband, John D. Henley Julian E. Dasher & wife, Florine H. Dasher

Grantee: Alva Lee Dasher (one-fourth interest)

4. Mecklenburg County Deed Book 953, Page 67 (July 22, 1938).

Grantee: C. O. Dulin & wife, Eva Faubert Dulin

Grantor: Ouida Dasher Brown, Doria Dasher Henley & Julian E. Dasher

5. Mecklenburg County Deed Book 944, Page 29 (March 11, 1938).

Grantor: Hoae Owners’ Loan Corporation of Washington, D.C.

Grantee: C. O. Dulin & wife, Eva Faubert Dulin

6. Mecklenburg County Deed Book 901, Page 154 (November 28, 1936).

Grantor: T. C. Abernethy, Commissioner

Grantee: Home Owners’ Loan Corporation of Washington, D.C.

7. Mecklenburg County Deed Book 797, Page 235 (December 8, 1933).

Grantor: Mrs. May Herndon Alexander (Widow)

Grantee: Home Owner’s Loan Corporation of Washington, D. C. (Deed of Trust)

8. Mecklenburg County Deed Book 617 , Page 427 (June 24, 1926).

Grantor: E. B. Herndon

Grantee: Hay Herdon Alexander

9. Mecklenburg County Deed Book 624, Page 250.

Grantor: Wardlaw P. Thomson, Trustee

Wardlaw P. Thomson & wife, Elizabeth Alexander Thomson May H. Alexander (widow)

Grantee: E. B. Herndon .

10. Mecklenburg County Deed Book 614, Page 203 (August 1, 1925).

Grantor: E. B. Herndon

Grantee: Wardlaw P. Thomson

11. Mecklenburg County Deed Book 445, Page 443 (May 16, 1921).

Grantor: Thaddeus A. Adams, John A. Coke, Jr., Trustees

Grantee: E. B. Herndon

12. Mecklenburg County Deed Book 358, Page 157 (March 15, 1916).

Grantor: R. O. A1exander & wife, May H. Alexander

Grantee: Thaddeus A. Adams & John A. Coke, Jr. (Deed of Trust)

13. Mecklenburg County Deed Book 174, Page 318 (February 2, 1903).

Grantor: J. L. Villalonga & wife, Constance M. Villalonga

Grantee: Robert O. Alexander

14. Mecklenburg County Deed Book 168, Page 178 (Apri1 28, 1902).

Grantor: Charlotte Consolidated Construction Co.

Grantee: Constance M. Villalonga, wife of J. L. Vlllalonga

15. Mecklenburg County Deed Book 156, Page 227 (May 10, 1900).

Grantor: Walter Brem & wife, H. C. Brem

Grantee: Mrs. Constance M. Villalonga

16. Mecklenburg County Deed Book 150, Page 609 (May 10, 1900).

Grantor: Charlotte Consolidated Conatruotion Co.

Grantee: Mrs. Constance M. Villalonga

Date of Preparation of this Report: June 4, 1978

Prepared by: Dr. Dan L. Morrill, Director

Charlotte Mecklenburg Historic Properties Commission

139 Middleton Dr.

Charlotte, N.C. 28207

Telephone: (704) 332-2726

Architectural Description

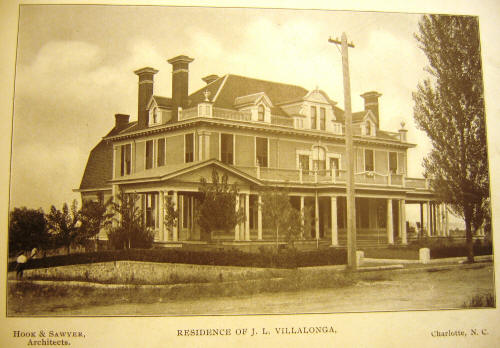

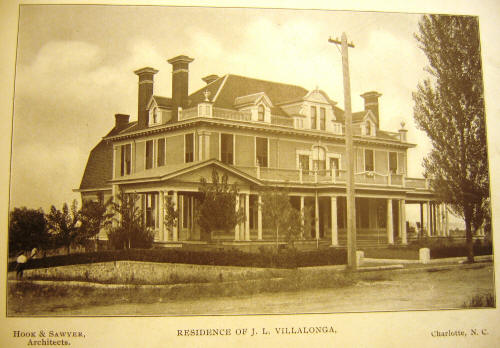

Residence of J.L. Villalonga was featured in “Some Designs,” a promotional booklet published by Hook & Sawyer ca. 1902.

The Villalonga-Alexander House, 301 East Park Avenue, Charlotte, built in 1900-1901, is the largest remaining private residence in the early suburb of Dilworth. The Colonial Revival style two and one-half story frame house has an unusually wide classical front porch which extends on the west side as a porte-cochere and on the right side as a balancing side porch. The well-preserved site contains a formally landscaped lawn, divided by a low rusticated granite retaining wall with granite cornerposts. A wide sidewalk leads to the center entrance and a driveway leads beneath the porte-cochere. Although the entrance hall, stair well, and roof of the house were destroyed by a 1948 fire and rebuilt, the remainder of the interior and exterior is well-preserved. The Villalonga-Alexander House is a product of the turn-of-the-century industrial boom which marked the beginning of the New South, yet retains the polite dignity and generosity of scale expressive of the Old South. The main block, five bays wide and four bays deep, rests on an unusually deep full brick basement, laid in random common bond, and is surmounted by a deep gable-on-hip (British gambrel) roof. The main facade is strongly centralized by the ornate center entrance, the scrolled pediment design of the porch balustrade above the center bay, the Palladian window in the center bay of the second story, and the large center roof dormer. The entrance consists of a replacement door (due to fire damage) set within an interesting classical framework, with fluted pilasters resting on a chair rail which continues across the entire main facade beneath the front porch. Flattened Ionic capitals cap the pilasters and support a lintel with an applied garland motif giving the appearance of hanging from the capitals. The Palladian window is a two-over-two round-arched sash with flanking one-over-one rectangular sash, set within a surround with a keystone over the center window. The gabled dormer, a replacement following the fire, has a solid curvilinear bargeboard and a one-over-one sash. A comparison of the present main facade with a photograph of the house in Art Work of Charlotte, North Carolina, a photographic album published in 1905, indicates that the roofline is considerably less ornate than it was originally. The flanking sash of the Palladian window originally had lozenge window panes, the newels of the porch balustrade were crowned with wooden finials, the dormers had ornate pediments, the center pediment adorned with a swag and scroll brackets, and a balustrade stretched between the dormers along the eaves, with heavy corner newels surmounted by large metal urns, These decorative details were not replaced after the 1948 fire, although the urns were rescued and are now stored in the basement.

A second front entrance is located in the western bay of the main facade, This double glazed door, located in the front face of the bay, has a single pane transom and replaces an original window. A corresponding bay is located on the other side of the main facade, but contains sash windows, The windows of the main block are one-over-one sash, with plain surrounds with molded lintels. These originally had louvered shutters. The door surrounds are identical to those of the windows, The walls are covered with narrow German siding. At each corner is a fluted cornerboard with an Ionic capital, echoing the main entrance treatment, eave treatment consists of a wide frieze and a boxed, molded cornice. The original roof was covered with wooden shakes, the post-fire replacement is covered with composition shingles. The three dormer windows of the main facade, also replacements, have one-over-one sash windows and gabled roofs with solid, curvilinear bargeboards. Two tall brick, interior end chimneys project from each side elevation, An additional chimney projects from the rear slope of the roof near the junction of the rear wing, Each chimney stack has a molded metal collar. The one-story rear wing is treated identically to the main block, except that the roof has a gambrel form, with dormer windows along the flanks, and an interior end chimney on the gambrel end. A door in the center west side bay of the wing leads to a rear stair. The outside steps which originally provided exterior access to this stair have been removed. The shed porch along the east side of the wing is a later addition. The one-story porch which stretches the length of the main facade is supported on Doric posts, paired on each side of the main entrance and tripled at the corners. The porch gives a tripartite division to the facade design, for the west porte-cochere bay and the east porch bay are each capped by a shallow pediment with a rough finish stucco tympanum and overhanging boxed, molded eaves. Between the pedimented bays is a roof balustrade with turned balusters, square newels with molded caps, and a scrolled pediment design in the railing above the entrance bay.

The twelve foot wide porch matches the other measurements of the house in scale. The porch originally extended partially along the east elevation, but has been enclosed. The wooden carriage steps leading from the driveway up to the porch floor, beneath the porte-cochere, are still in place. The interior finish of the Villalonga-Alexander House represents the lavish eclecticism of turn-of-the-century American architecture. The plan, true to the pre-Revolutionary houses which the Colonial Revival style was based upon, has no center hall. A series of rooms is arranged in a circular pattern around the fireplace and stair in the center of the house. Unlike Colonial floor plans, the rooms of the Villalonga-Alexander House were originally linked by double sliding doors so that the entire first floor became a relatively continuous open space. All of these double doors remain except those in the side walls of the entrance hall, which were not replaced during the post-fire reconstruction. The plan consists of a center entrance hall, at the rear of which is the main stair, with a parlor and library on the west, another parlor and dining room on the east The rear wing contains the kitchen with a butler’s pantry between the main block and the kitchen. Directly behind the entrance hall is a room which was originally the conservatory, with two-over-two sash windows lining the east wall. The partition between the butler’s pantry and conservatory was removed and this large room is now a den. The second floor contains a large center hall, with a narrower hall extending to a bathroom on the east end, with five bedrooms flanking the hall. In the northwest corner of the stair landing to the second floor is a stair leading to the large attic. The rear wing has a narrow hall along the east side and a large bedroom and bath. The rear stair, accessible from the outside, opens into this hall. The rear wing probably served as servants’ quarters. The center area of the house, including the entrance hall and stair, a portion of the dining room, and the second floor hall and attic, was destroyed by the 1948 fire. This has been rebuilt in a compatible style but is obviously of more recent vintage. The entrance hall, originally the most ornate room in the house, had a parquet floor, a carved oak wainscot, exposed ceiling joists, ornate paneled oak doors, and an unusual brick fireplace. The only original feature which survived the fire is the fireplace, which did not burn because it is constructed completely of brick and terra cotta tile.

The origin of its design and placement beneath the staircase is in the Colonial Revival style houses constructed in the 1880s in New England by H. H. Richardson. In his designs, he intermingled round brick arches and richly molded tilework derived from Romanesque European architecture with native 18th century forms. He also favored the use of the medieval entrance hall, with the fireplace and stair as the physical and symbolic core of the house. His houses were the models for many Colonial Revival architects during the late 1900s and early 1900s. Most notable were McKim, Mead, White, who worked primarily in New York and New England. Designers in Norch Carolina generally followed the Queen Anne and Neo-Classical Revival styles, and the Colonial Revival style did not attain general popularity in the South until the 1920s. The Villalonga-Alexander House entrance hall fireplace consists of a broad, elliptically arched opening with four molded tile archivolts (semicircular molded bands), a brick shelf with a double egg and dart cornice, and a flat-paneled brick overmantel outlined by a rich tile surround with interlace designs. It was probably imported from the North. The dining room, the largest room in the house and now the most ornate room in the house, has a parquet floor, paneled doors with applied, hand-carved wooden garland ornament, and a magnificent Renaissance Revival style mantel with overmantel. This room also had a paneled wainscot, but it was removed because of damage during the 1948 fire. The mantel is executed in darkly stained oak, and contains terns (pedestals tapering towards the base and merging at the top into a mythical animal) which support the frieze and shelf. The shafts of the terms are decorated with applied floral ornament reflecting the influence of Pompeiian wall decoration which was revived in the Renaissance. At the top of each tern is a ferocious lion with bared teeth. This mantel was probably also imported. The light fixture of Tiffany design which originally hung above the dining room table is now in storage, and is the only original light fixture which has survived. The decorative finish of the remaining rooms is Neo-Classical Revival in style, and is typical of the woodwork found in most North Carolina houses of this period. It is in sharp contrast with the New England flavor of the entrance hall fireplace and the Baroque richness of the dining room mantel.

The mantels, no two of which are alike, have free-standing or engaged classical columns or posts, friezes adorned with applied floral and garland ornament, and molded shelves, often with a paneled overmantel. The first floor mantels are more ornate than those on the second floor. The hearth and fireplace surrounds are paved with ceramic tile, and have iron surrounds. At least one of the fireplaces has an ornate metal lining. The other fireplace openings have been sealed, and are not visible. The walls and ceilings throughout are plastered. The first floor main block rooms have parquet floors in a herring bone pattern of identically stained oak strips, with a herring bone border of oak strips of alternating dark and light stains around tile perimeter of each room. Throughout the remainder of the house are narrow plain oak floors. The original door and window trim of the first floor main block consists of wide surrounds with small egg and dart moldings. The second floor of the main block and both floors of the rear wing have simple molded door and window surrounds. The single doors throughout the house are flat-paneled. The aprons of the windows in the two front parlors and the library are flat-paneled, with flanking wide pilasters supporting wide window sills. Several of the pilasters have a fluted effect created by attached wooden strips. Several of the bathrooms retain interesting, original built-in marble sinks. The kitchen has a huge gas hotel range bought in 1938. This was necessary to feed the numerous boarders that the present owner and her mother before her have kept. The basement, which occupies the entire space beneath the main block, is one of the most unusual areas of the house because of its height…approximately fifteen feet.

Victoria

Victoria