SURVEY AND RESEARCH REPORT

On The

Woodlawn Avenue Duplex

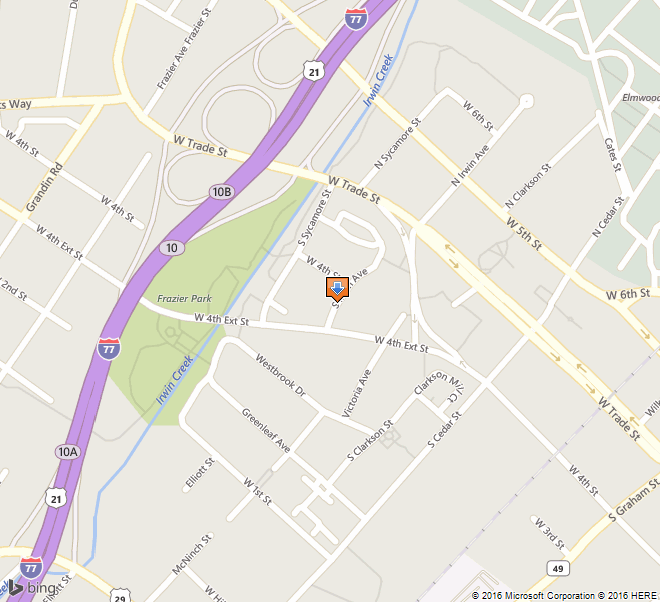

1. Name and location of the property: The property known as the Woodlawn Avenue Duplex is located at 210 South Irwin Ave, in Charlotte, North Carolina. Its UTM location is 17 513226E 3898947N

2. Name and address of the present owner of the property:

T Hardy Investment Group LLC

PO Box 621085

Charlotte, NC 28262

3. Representative photographs of the property: This report contains representative photographs of the property.

4. Maps depicting the location of the property: This report contains a map depicting the location of the property.

5. Current deed book and tax parcel information for the property:

The Tax Parcel Number of the property is 07321509. The most recent deed reference to this property is 20473-984, recorded in Mecklenburg County Deed Book

6. A brief historical sketch of the property: This report contains a brief historical sketch of the property.

7. A brief architectural and physical description of the property: This report contains a brief architectural description of the property.

8. Documentation of why and in what ways the property meets criteria for designation set forth in N. C. G. S. 160A-400.5:

a. Special significance in terms of its history, architecture, and/or cultural importance: The Commission judges that the property known as the Woodlawn Avenue Duplex does possess special significance in terms of Charlotte-Mecklenburg. The Commission bases its judgment on the following considerations:

1) The Woodlawn Avenue Duplex is a prominent reminder of the early 20th century residential nature of Charlotte, and is thus an important artifact that can help us understand the city’s built environment which has been radically altered by both the commercial development of Charlotte after World War II, urban renewal, and the recent phenomenal commercial and residential development of the Uptown.

2) The Woodlawn Avenue Duplex is a well-preserved example of a small two-story duplex, which was once a common component of the Uptown residential landscape but is now the among the rarest of the historic building types.

3) The Woodlawn Avenue Duplex demonstrates both the diversity of residential building types and the social and economic diversity that once existed in the city neighborhoods but was not found in much of the residential development in Charlotte after World War II.

4) The Woodlawn Avenue Duplex is one of the few surviving buildings that were part of Woodlawn, an early streetcar suburb.

b. Integrity of design, setting, workmanship, materials, feeling and/or association: The Commission contends that the physical and architectural description which is included in this report demonstrates that the Woodlawn Avenue Duplex in Charlotte, N.C. meets this criterion.

9. Ad Valorem tax appraisal: The Commission is aware that designation would allow the owner to apply for an automatic deferral of 50% of the Ad Valorem taxes on all or any portion of the property which becomes designated as a “historic landmark.”

Date of preparation of this report: December 2006

Prepared by: Stewart Gray

Historical Context Statement for the Woodlawn Avenue Duplex

Residential Housing in the Center City

Once largely residential, Charlotte’s urban core now contains a much-reduced collection of historic residential buildings. Due to Urban Renewal during the 1960s and 1970s, entire residential neighborhoods near the city’s urban core have been obliterated. Second Ward, which consisted of roughly a quarter of the city in the 19th century, now contains only housing in modern apartment buildings currently being constructed, The Brooklyn neighborhood occupied much of Second Ward and was once arguably the cultural center of the city’s African-American community. Today only a school gymnasium, one commercial building, and a church survive. Blandville, an African-American neighborhood that existed to the south of Morehead Street, was also negatively impacted by Urban Renewal. The building of a new expressway, warehouses, shops, and factories contributed to the conversion of the Blandville neighborhood into a strictly industrial/commercial area. Of the hundreds of homes that once populated Blandville, only one house with integrity still exists.

House on Dunbar Street in Blandville

House on Dunbar Street in Blandville

This phenomenon of neighborhood eradication in Charlotte was not limited to black neighborhoods. In the 19th Century, the homes of the city’s wealthiest and most influential citizens lined its two dominant streets, Trade and Tryon. Many of these homes survived into the middle years of the 20th century. None now exists. A collection of historic homes dating from the late nineteenth century has survived in the Fourth Ward and are part of the locally designated Fourth Ward Historic District. But outside Fourth Ward, historic residential buildings in the Urban Core are rare. The William Bratton House was built around 1923 in Charlotte’s First Ward. The home of a Duke Power engineer, it was situated amid a streetscape of single-family houses and duplexes built for middle and upper-middle class whites. Today, it is the only surviving residential building along North Brevard Street. The house, now an office, faces east on a flat lot, bordered by vacant lots and parking lots. Only one other pre-World War II home has survived in the Ward, which once featured hundreds of homes.

William Bratton House, ca. 1923

William Bratton House, ca. 1923

631 North Brevard Street

The near-complete loss of historic residential buildings in the Center City makes it difficult for the public to understand the pre-World War II history of Charlotte based on the current built environment. This scarcity of historic resources endows the surviving neighborhoods and exceptional individual buildings in those neighborhoods with special significance if they have retained their integrity.

Woodlawn Neighborhood

The development of the Woodlawn Neighborhood was part of the phenomenal growth that Charlotte experienced in the early years of the twentieth century. Between 1900 and 1910, the city’s population grew 82%, from18,091 to 34,014. In response, the city expanded physically, with its boundaries moving outward to incorporate former farmland. From 1885 to 1907, the city’s area grew 570%. This incredible growth continued with the city’s population reaching 82,675 by 1930. [1] To accommodate the new citizens, real estate developers such as F. C. Abbott, George Stephens and B. D. Heath built neighborhoods that were linked to the city by the expanding streetcar systems. [2] Some of these neighborhoods, such as Myers Park, Wilmore, and Washington Heights, have survived. Others, such as Oakhurst (now in Plaza Midwood), Piedmont Park (now part of Elizabeth), and Woodlawn (now considered part of Irwin Park or Third Ward) were absorbed into larger neighborhoods and have lost their distinct historic identities.

Woodlawn resulted from a decision by the Continental Manufacturing Company to develop its surplus land in Charlotte’s Third Ward into a residential neighborhood. Development began around 1907. Although located inside one of the City’s original four wards, the neighborhood was promoted as a suburb, perhaps due to the developing success of Charlotte’s first true streetcar suburb, Dilworth. Streetcar lines radiated out from the center of the city, and along these lines neighborhoods called “streetcar suburbs” sprang up. Woodlawn was one of these neighborhoods, and it was served by the West Trade Street streetcar line. The close-in nature of the neighborhood may have been one of its selling points. A 1911 advertisement proclaimed “Woodlawn is the nearest suburb to the business part of the city, yet NONE is prettier.” [3]

Woodlawn was never a large neighborhood. Originally platted along just four streets, it appears that soon after the small neighborhood was built it began to loose its original identity. The 1911 Sanborn Maps show the small neighborhood labeled as Woodlawn. Virginia Woolard, who grew up in the neighborhood on Grove Street in the 1940s, does not recall that her neighborhood ever had a name.[4] Instead one would simply refer to the street name to identify where they lived. Still, the original identity of the neighborhood was retained to some extent with the name of its principal street, Woodlawn Avenue. This final link to the historic name of the neighborhood was lost when the curving Woodlawn Avenue was renamed. A short street, Woodlawn Avenue never contained more than 22 buildings. In 1953 a new road named Woodlawn Road appeared in the city directory. It also contained around 20 homes. But this new road was located to the south of the city where suburban development exploded after World War II. By 1959, hundreds of new homes lined Woodlawn Road, which became a major thoroughfare feeding the city’s new suburban residential, and commercial development. The two blocks that had been labeled Woodlawn Avenue were renamed Irwin Avenue South, to avoid confusion with the robust roadway to the south.

Duplexes

The Woodlawn Avenue Apartments is a duplex with distinct upstairs and downstairs units. While some good examples of early-twentieth-century duplexes survive in the outlying suburbs of Elizabeth, Dilworth, and Plaza Midwood, the story in the city’s historic core is quite different. A survey of Charlotte’s Center City conducted by the Charlotte Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission in 2004 identified fifty-two individual properties that could potentially be designated as historic landmarks. Of these, only two were duplexes: the Woodlawn Avenue Apartments, and the North Myers Street Duplex. This low number is especially dramatic when a review of Sanborn Maps shows that duplexes, as well as quadraplexes, were a common feature in the Center City. Identified in the 2004 survey, the North Myers Street Duplex is an important reminder of the historic residential nature of First Ward. Unfortunately, the historical context of the building has been lost, as it is now the sole survivor of a residential neighborhood and is now, like the William Bratton House, surrounded by vacant lots, parking lots, and sprawling late 20th- and 21st-century commercial buildings. In contrast, the Woodlawn Apartments is located amidst a small collection of surviving single-family homes. The remnant of the Woodlawn neighborhood around the Woodlawn Apartments concretely demonstrates what the old directories and fire insurance maps indicate that duplexes and other multi-family residential buildings were commonly intermingled with single-family homes in early twentieth-century neighborhoods.

Myers Street Duplex

Myers Street Duplex

Sanborn maps from 1953 indicate that duplexes were still a common building type in the Center City landscape at least until the middle years of the 20th century. In First Ward the block formed by 8th and 9th Streets and North Brevard and Caldwell streets contained twenty-seven closely spaced residential buildings. Of those, at least 15 appear to have been duplexes. Not all residential sections contained such a high percentage of duplexes. In the city’s Fourth Ward, the block surrounded by 9th and 8th streets, Graham and Smith Streets contained 21 residential buildings with five of those being duplexes. A review of the Sanborn maps clearly indicates that nearly every single block of residential buildings in the four wards once contained duplexes.

In Charlotte, this historic housing pattern was largely abandoned after World War II when the new suburban neighborhoods were strictly segregated into either single-family or multi-family groups.

Woodlawn Avenue Duplex

Built between 1926 and 1929[5], the Woodlawn Avenue Duplex was very much part of the “everyday” architecture of Charlotte’s urban core before World War II. Blue-collar and lower level white-collar workers lived there for much of the 20th Century. In 1934, 208 Woodlawn, the upper unit of the duplex, was occupied by Harry and Mary Fine. Harry was listed as a clerk with the Southern Public Utilities Company, which later became Duke Power. Downstairs in 210 Woodlawn lived William and Frances Craig. William’s occupation is listed as Traveling Salesman. The Fines and the Craigs lived in a neighborhood principally of singles-family houses. The only other multi-family buildings in the small Woodlawn Neighborhood were the quadraplex next door and the four-unit Woodlawn Terrace Apartments. More transitory than their neighbors who generally owned their own homes[6], the tenants in the duplex were different by 1942. That year “credit manager” James Strawn lived in 208 Woodlawn and machinist Herbert Crouch and his wife Diamond lived in 210.

The Woodlawn Avenue Duplex continued to function as a duplex through the 1960s even as the nature of the neighborhood changed. Like most of Third Ward, the Woodlawn neighborhood saw an outflow of white residents as the suburbs of the city expanded. Facing a dwindling supply of housing in the city’s Urban Core, black Charlotteans moved into the once segregated Woodlawn neighborhood.

While many of the original neighborhood homes have survived, the Woodlawn Duplex is the only multi-family residential building in the neighborhood to have survived with a good degree of integrity. The neighboring quadraplex has been significantly altered, and the Woodlawn Terrace Apartments have been lost. A wider survey of Third Ward indicates that the Woodlawn Duplex is the only surviving duplex in the entire ward.

In the context of a vastly changed city, the Woodlawn Duplex is an important artifact that can help us understand the early 20th century residential nature of Charlotte. It is a prominent relic of a reduced neighborhood whose original identity has been lost. It is helpful in understanding the many small neighborhoods that were absorbed into larger ones. It is representative of a once-common housing type that that has disappeared completely from Charlotte’s center city neighborhoods.

Woodlawn Avenue Duplex

Before 2005 Renovation

Architectural Description

The Woodlawn Duplex is a two-story brick-veneered building. Although detailing is restrained, the ca. 1928 duplex appears to be a late, vernacular example of the Mission Style, with the shaped parapet and arched porch being the most distinguishing elements. The exposed rafter ends of the duplex’s porch roofs fit with the style and would have been a feature familiar to Charlotte’s builders who, up until World War II, continued to utilize elements of the Craftsman Style. Another link with the local tenacity of the Craftsman Style is the duplex’s bracketed shed-roof over the entrance. This is an element found on several Craftsman Style duplexes and quadraplexes in the fairly intact Charlotte suburbs of Dilworth and Elizabeth.

The building faces east and is four bays wide with a two-story porch centered on the façade. The lower story of the porch features two brick posts connected with segmental-arches that appear to be supported by curved boxed-in wooden lintels. In contrast to the masonry lower porch, the upper story features square wooden posts that support a built-up exposed beam that in turn supports the shed roof’s rafters. The rafter ends are fancifully sawn with double curves. The porch ceiling and in-fill walls are covered with original tongue-and-groove narrow boards.

The façade is veneered with wire-cut brick. A watertable is delineated with a soldier-course of brick resting on a solid brick foundation that has been stuccoed smooth. All exterior doors and windows have been replaced. Wall openings on the second story are aligned with those on the first. On both stories the southernmost bay contains double metal casement windows that replaced original metal casements. The windows feature simple brick sills, and soldier-courses delineate the lintels. On both stories, the porch shelters a door opening and another double-window opening. The northernmost bay contains the main entrance to the duplex. A shed roof shelters the door and is supported by two large brackets with curved braces. The rafter ends are also sawn with a single curve. The door was originally bordered with multi-pane sidelights, which have been replaced with single-light sidelights. This doorway was originally only the entrance to the upper apartment of the duplex. The original entrance to the lower apartment was accessed through the porch. Metal railing now blocks this entrance, and both apartments share a single entrance. Above the doorway is a single metal casement.

The façade features a parapet with flat and curvilinear coping. The raised center section of the parapet is highlighted with a cross pattern in the brickwork.

South Elevation

North Elevation

The side elevations lack the architectural features of the façade. The south elevation is pierced by four window openings. The north elevation is pierced by a small window opening set between the upper and lower stories that lights the stairwell.

A narrow alley runs behind the building. Sanborn maps indicate that the duplex originally had automobile parking in the basement. The bays for the auto parking are now obscured with stucco. Unlike on the other elevations, the fenestration on the rear of the building has been somewhat altered. An original short window has been infilled, and one double-window opening has been reduced to the size of a single window opening.

[1] Dan Morrill “Center City Housing” http://landmarkscommission.org/uptownsurveyhistoryhousing.htm

[2] Tom Hanchett “The Growth of Charlotte: A History” http://www.cmhpf.org/educhargrowth.htm

[3] Ibid

[4] Conversation with Virginia Woolard, October 2006. Notes on file with the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission.

[5] The building is not listed in the 1926 City Directory, but does appear in the 1929 Sanborn Maps.

[6] Home ownership indicated in 1942 City Directory.

.jpg)

This report was written May 6, 1981.

1. Name and location of the property: The property known as the Atherton Mill House is located at 2005 Cleveland Ave. in Charlotte, N.C.

2. Name, address and telephone number of the present owner and occupant of the property:

The present owner and occupant of the property is:

Ruth A. Purser

2005 Cleveland Ave.

Charlotte, N.C. 29203

Telephone: none

3. Representative photographs of the property: This report contains representative photographs of the property.

4. A map depicting the location of the property: This report contains a map which depicts the location of the property.

5. Current Deed Book reference to the property: The most recent deed to this property is listed in Mecklenburg County Deed Book 3090 on Page 540. The Tax Parcel Number of the property is 121-067-11.

6. A brief historical sketch of the property:

The Atherton Cotton Mill in Dilworth, which opened in April 1893, was the first mill which the D. A. Tompkins Company, named for its founder and president, Daniel Augustus Tompkins (1851-1914), owned and operated. 1 A native of Edgefield County, S.C., and graduate of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, N.Y., Tompkins had arrived in Charlotte in March 1883. 2 Having served for several years as a chief machinist of the Bethlehem Iron Works in Bethlehem, Pa., he secured a franchise from the Westinghouse Machine Company to sell and install steam engines and other industrial machinery, and selected Charlotte as the location for his company because of the excellent railroad facilities which the community possessed. 3 The D. A. Tompkins Company opened for business on March 27, 1883. 4

D. A. Tompkins

Daniel Augustus Tompkins exercised a profound influence upon the socioeconomic development of the South during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Through such organs as the Charlotte Observer, which he established in February 1892, he became an effective advocate of the industrialization and agricultural diversification of his native region. 5 In keeping with his commitment to these priorities, Tompkins promoted and encouraged the establishment of cotton mills and cotton seed oil mills throughout the South. In 1887, he became a co-founder of the Southern Cotton Oil Company, which constructed and operated eight cotton seed oil mills covering a region from Columbia, S.C., to Houston, Tex. Indeed, Tompkins is regarded as a pioneer in the cotton seed oil business. 6 Between 1885 and 1895, for example, the D. A. Tompkins Company designed and erected at least forty-seven mills for processing cotton seeds. 7 In October 1906, Tompkins stated that his firm had “built something over 100 cotton mills and not less than 250 cotton seed oil mills. “ 8

Construction of the Atherton Mill at Dilworth began on August 23, 1892. 9 Containing ten thousand producing spindles and five thousand twisting spindles, the plant manufactured two to four ply yarns, sizes twenty to fifty. 10 An essential component of the operation was the mill village. On February 23, 1893, the D. A. Tompkins Company purchased an entire block in Dilworth on which to erect twenty houses for its workers at the Atherton. 11 Remarkably, seven of these dwellings survive, six on Euclid Ave. and one on Cleveland Ave. 12

The houses in the Atherton mill village attained regional importance, because D. A. Tompkins used them as illustrations in textbooks, most notably his Cotton Mill: Commercial Features (1899), which he published to instruct and assist the builders of cotton mills. 13 According to one scholar, Tompkins’ books were the “most influential of all publications in this period. ” 14 In Cotton Mills: Commercial Features, Tompkins provided specifications and plans for five types of mill houses. 15 He also set forth the fundamental principle which undergirded his concepts of design. “The whole matter of providing attractive and comfortable habitations for cotton mill operatives in the South,” Tompkins asserted, “may be summarized in the statement that they are essentially rural people. ” 16 He spoke to the same point in a letter which he wrote on October 15, 1906, to a textile official in Patterson, N.J. Tompkins defended his practice of not placing closets, bathrooms or hot water in his mill houses by explaining that the majority of his laborers had grown up in rural areas, where such “modern improvements” were unknown. “Sometimes they would object to ordinary clothes closets,” he reported, “on the plea that they were receptacles for worn out shoes and skirts that ought to be thrown away and destroyed.” In the same letter, Tompkins answered the charge of those who insisted that he was derelict in not erecting brick row houses like those found in the industrial cities of the North. Again, he justified his actions by emphasizing the rural background of his mill workers. He argued that frame cottages on individual lots were more in keeping with the desires and proclivities which his laborers had brought from the farm. Tompkins went on to explain that his mill villages contained “three or four different standard houses” which were scattered throughout the community to create the impression that they had been built “by individuals instead of by the corporation. ” 17

|

| Plan for Mill House published in D. A. Tompkins’s Cotton Mills: Commercial Features |

The D. A. Tompkins Company took pride in its ability to create what it regarded as an hospitable environment for its workers. The Atherton Lyceum on South Boulevard offered evening courses for the mill hands, many of whom were women and children. 18 Indeed, examples of paternalism abounded at the Atherton. “Arrangements should be made to inspect at regular intervals the operatives houses and yards,” Tompkins exclaimed. 19 Tompkins often boasted about the nurturing relationship which he had with his mill hands. For example, he acquired flower seeds and vegetable seeds for them and even gave them trees to plant in their yards. He went so far as to award an annual cash prize for the best garden in the village. On July 4, 1907, he sponsored a picnic at the Catawba River, where his workers were served sandwiches and lemonade. 20 No doubt Tompkins was pleased by the comments of a group of textile executives who visited the Atherton community in May 1900. “The Atherton and its surroundings are marvels of beauty,” one declared. “There is nothing to approach it in any factory settlement I have seen in the North. ” 21

There is ample reason to believe that life in the Atherton mill village had its disadvantages. Tompkins used the so-called “rough rule” in assigning families to his residential units, meaning that a mill hand was to be supplied for every room in the house. The rent ranged from 75 cents to $1.00 per room per month. 22 Cotton mills were noisy and dangerous places. Indeed, the people of Charlotte called them “hummers” because of the deafening din which their machines produced. 23 Accidents at the Atherton were numerous, such as the mangling of a worker’s hands in June 1893 or the death of an overseer in the carding room in October 1902, when he became entangled in the belting apparatus. “He was dead in six seconds,” the Charlotte Observer reported. 24

Daniel Augustus Tompkins died on October 18, 1914, at his home in Montreat, N.C. 25 The Atherton Mill continued to operate until the mid 1930’s, however. 26 And the factory building still stands at 2136 South Boulevard. 27 According to Tompkins’ biographer, the three textile mills which Tompkins owned and operated, including the Atherton at Dilworth and mills at High Shoals, N.C., and Edgefield, S.C., “were the enterprises which, in large measure, molded Tompkins’ social and political philosophy. ” 28 Consequently, these mills and their attendant mill villages possess enormous historic significance in terms of the evolution and development of the Southern textile industry in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This truth is even more obvious when comes to understand that houses like those at 2005 Cleveland Ave. in Charlotte were manifestations of standards which had a regional impact.

Notes

1 Howard Bunyan Clay, “Daniel Augustus Tompkins: An American Bourbon,” (An unpublished doctoral dissertation at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, N.C.), p. 103. Charlotte Observer (April 12, 1893), P. 4.

2 Clay, p. 25.

3 Ibid., p. 24.

4 Ibid., p. 25.

5 Ibid., p. 59.

6 Ibid., p. 32.

7 Ibid., p. 34.

8 “D. A. Tompkins to R. T. Daniel,” (A letter in the D. A. Tompkins Papers in the Southern History Collection at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, N.C.).

9 Charlotte Observer (August 31, 1892), p. 4. 10 Clay, p. 104.

11 Mecklenburg County Deed Book 90, Page 310. Charlotte Observer (March 22, 1893).

12 The houses are at 2005 Cleveland Ave. and at 2000, 2004, 2016, 2020, 2024 and 2028 Euclid Ave. The house at 2005 Cleveland Ave. is the least altered from the original.

13 D. A. Tompkins, Cotton Mill: Commercial Features (Observer Printing House, Charlotte, N.C., 1899).

14 Brent Glass, “Southern Mill Hills: Design in a ‘Public’ Place” in Doug Swaim, ed., Carolina Dwelling (The Student Publication of the School of Design, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, N.C., 1978) vol. 26, p. 143.

15 Sketches of these designs are included in this report.

16 Tompkins, p. 117.

17 “D. A. Tompkins to J. A. Barbour,” (A letter in the D. A. Tompkins Papers in the Southern History Collection at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, N.C.).

18 Clay, p. 106. For a photograph of the Atherton Lyceum, see Tompkins, Cotton Mill: Commercial Features, Fig. 44.

19 Tompkins, p. 118.

20 Clay, pp. 110-111.

21 Charlotte Observer (May 12, 1900), p. 8.

22 Clay, p. 105.

23 Charlotte Observer (November 27, 1892), p. 4.

24 Charlotte Observer (June 28, 1893), p. 4. Charlotte Observer (October 14, 1902), p. 5

25 Clay, p. 317. His house at Montreat survives.

26 Hill’s Charlotte City Directory 1934 (Hill Directory Co., Richmond, Va., 1934), p. 602. Hill’s Charlotte City Directory 1935 (Hill Directory Co., Richmond, Va., 1935), p. 645.

27 The old Atherton Mill is at 2136 South Boulevard and houses the Stacey Knit Company.

28 Clay, p. 164.

7. A brief architectural description of the property: This report contains an architectural description of the property prepared by Dr. Dan L. Morrill, Director of the Commission.

8. Documentation of why and in what ways the property meets the criteria set forth in N.C.G.S. 160A-399.4:

a. Special significance in terms of its history, architecture, and/or cultural importance: The Commission judges that the property known as the Atherton mill house does possess special significance in terms of Charlotte-Mecklenburg. The Commission bases its judgment on the following considerations: 1) it is one of the few extant mill houses in Charlotte-Mecklenburg which was initially owned by the D. A. Tompkins Company; 2) it is the best preserved remnant of the Atherton mill village; 3) it is one of the oldest houses in Dilworth, Charlotte’s initial suburb; and 4) it is one of the earliest examples of a type of mill house which D. A. Tompkins promoted in his influential textbooks for mill owners.

b. Integrity of design, setting, workmanship, materials, feeling and/or association: The Commission judges that the architectural description included in this report demonstrates that the property known as the Atherton mill house meets this criterion.

9. Ad Valorem Tax Appraisal: The Commission is aware that designation would allow the owner to apply annually for an automatic deferral of 50% of the Ad Valorem taxes on all or any portion of the property which becomes “historic property.” The current Ad Valorem Tax appraisal on the Atherton mill house is $860. The current Ad Valorem Tax appraisal on the .146 acres of land is $5,080. The land is zoned for industrial use.

Bibliography

Charlotte Observer.

Howard Bunyan Clay, “Daniel Augustus Tompkins: An American Bourbon.” (An unpublished doctoral dissertation at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, N.C.).

Brent Glass, “Southern Mill Hills: Design in a ‘Public’ Place,” in Doug Swaim, ed., Carolina Dwelling (The Student Publication of the School of Design, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, N.C., 1973) vol. 26.

Hill’s Charlotte City Directory 1934 (Hill Directory Co., Richmond, Va., 1934).

Hill’s Charlotte City Directory 1935 (Hill Directory Co., Richmond, Va., 1935).

Records of the Mecklenburg County Register of Deeds Office.

Records of the Mecklenburg County Tax Office.

D. A. Tompkins, Cotton Mill: Commercial Features (Observer Printing House, Charlotte, N.C., 1899).

D. A. Tompkins Papers in the Southern History Collection at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, N.C.

Date of the Preparation of this Report: May 6, 1981.

Prepared by: Dr. Dan L. Morrill, Director

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Properties Commission

3500 Shamrock Dr.

Charlotte, N.C. 28215

Telephone: (704) 332-2726

In his Cotton Mill: Commercial Features, D. A. Tompkins sets forth the plans and specifications for what he calls a “Four-Room Gable House.” Moreover, he includes a photograph of this type of abode (Fig. 37). The house at 2005 Cleveland Ave. is a remarkably well-preserved example of this style, which Tompkins estimated in 1899 would cost $400 to erect. It is a one-story frame house with horizontal clapboard siding which is painted white. The structure rests upon brick piers, some of which have been replaced, with cinder or concrete block in-fill of more recent origin. The roof of the three-bay wide by one-bay deep main block is a gable roof of asbestos shingle with a cross gable at the center front. Diamond-shaped ventilators appear in the gable ends and in the cross gable. Rear ells extend from both sides of the back. The windows are four-over-four, double-hung sash throughout. Two brick chimneys with simple, corbeled caps pierce the roof. The original rear porch is unchanged except for the addition of a water closet.

This writer was unable to obtain permission to enter the house. However, he did talk with the daughter of the owner, and she indicated that the interior was essentially unchanged from the original. Initially, the house would have contained four bedrooms, two on each side of a center hall. it is reasonable to infer that they would have been devoid of ornamentation.

This report was written July 14, 1997

1. Name and location of the property: The property known as the Atherton Cotton Mills is located at 2108 South Boulevard in Charlotte, North Carolina.

2. Name, address and telephone number of the present owners of the property:

The owners of the various units in the building and the adjacent parking lot are listed on the attached sheet. The Atherton Condominium Owners Association can be contacted through:

Atherton Condominium Owners Association

c/o Meca Properties

908 South Tryon Street

Charlotte, N.C., 28202

Telephone: 704/372-0005

3. Representative photographs of the property: This report contains representative photographs of the property.

4. A map depicting the location of the property: This report contains a map which depicts the location of the property.

5. Current Deed Book Reference to the property: The most recent references to this property are recorded in Mecklenburg Deed Books by individual unit.

6. A brief historical sketch of the property: This report contains a brief historical sketch of the property prepared by Dr. Richard Mattson and Dr. Dan L. Morrill.

7. A brief architectural description of the property: This report contains a brief architectural description of the property prepared by Dr. Richard Mattson and Dr. Dan L. Morrill.

8. Documentation of why and in what ways the property meets the criteria for designation set forth-in N.C.G.S. 160A-399.4.

a. Special significance in terms of its history, architecture, and/or cultural importance: The Commission judges that the property known as the Atherton Cotton Mills does possess special significance in terms of Charlotte-Mecklenburg. The Commission bases its judgment on the following considerations: 1) the Atherton Cotton Mills was one of only three spinning mills owned and operated by Daniel Augustus Tompkins (1851-1914), a New South industrialist of profound importance in the economic development of Charlotte and its environs, 2) the Atherton Cotton Mills documents the emergence of Charlotte as a major textile manufacturing center in the later nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and 3) the Atherton Cotton Mills was the first industrial plant in the industrial district of Dilworth, Charlotte’s initial streetcar suburb.

b. Integrity of design, setting, workmanship, materials, feeling, and/or association: The Commission contends that the architectural description by Dr. Richard Mattson and Dr. Dan L. Morrill which is included in this report demonstrates that the Atherton Cotton Mills meets this criterion.

9. Ad Valorem Tax Appraisal: The Commission is aware that designation would allow the owner to apply for an automatic deferral of 50% of the Ad Valorem taxes on all or any portion of the property which becomes “historic property.” The current appraised value of the improvement is $3,771,620. The current appraised value of the land is $1,213,000. The total appraised value of the property is $4,984,620. The property is zoned UMUD.

Date of Preparation of this Report: July 14, 1997

Prepared by: Dr. Dan L. Morrill

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission

2100 Randolph Road

Charlotte, N.C., 28207

Telephone: 704/376-9115

The Atherton Cotton Mills facility also has architectural significance. This well-preserved factory, recently converted into condominiums, clearly represents in its basic form, materials, construction, and restrained design elements textile mills erected throughout Charlotte and the region during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The mill illustrates the “slow burn,” “standard mill construction” promoted by the New England Mutual fire insurance companies. In a fire, the stair tower, for example, could be closed off from the main facility, thus confining the spread of flames. The hardwood floors and thick structural timbers would char but retain their strength rather than collapsing as iron did in intense heat. The rows of windows along the long brick walls of the mill provided air and natural light for the men, women, and children who typically labored 60 hours per week producing yarn at the Atherton plant.

Young workers at the Atherton Mills

Location and Site Description

The Atherton Cotton Mills occupies a parcel of land along the South Boulevard industrial corridor of the Dilworth neighborhood in Charlotte. Located approximately in the middle of the block, the tract is bounded by the Norfolk Southern Railway right-of-way to the west, and the Parks-Cramer Company property to the north. Large, paved parking lots have been constructed on the east and west side of the buildings as part of the conversion of the Atherton Cotton Mills into condominiums. The proposed designation includes the exterior of the Atherton Cotton Mills building and all the land beneath and in the parking lots adjacent to the structure.

Architectural Description of the Atherton Cotton Mills Building

The exterior of the Atherton Cotton Mills building is remarkably intact, having undergone little alteration since the turn of the century, except for loss of its tower and the destruction of part of the powerhouse and machine shop during the conversion of the structure into condominiums. The Atherton Cotton Mills was housed in a single building with the longitudinal plan common to nineteenth century textile factories. Oriented north-south, the building was constructed on a slope, which provided two floors of work space on the west side and a single story on the east, facing South Boulevard. The plan is rectangular although the powerhouse and machine shop and several stairwells and additions do project from the west side, and a small office extends from the east elevation. The building measures 498 feet long and 78 feet wide. The building has a structure of heavy mill construction, reflected in the pilastered brick exterior walls covered in stucco. The foundation is also brick. The roof is a shallow pitched gable, supported by wooden trusses. On the north and south elevations, the roof line is defined by stepped parapets, while on the east and west sides, the gable roof ends in exposed wooden rafters and a wooden fascia. The main floor has numerous tall, recessed, segmental arch windows. New wooden platforms with pipe balustrades and modified doorways have been built to permit access to the condominiums. All the entrances are elevated over a paved drainage ditch which runs the length of the east elevation and the half windows which provide light to the lower floor. The powerhouse and machine shop form one extension from the northwest side of the main mill. On the south side of the powerhouse is a tall, massive square, brick smokestack with flared base and corbeled cap.

Development of the Atherton Cotton Mills

On July 18, 1892, Daniel Augustus Tompkins, R.M. Miller, Jr., and E.A. Smith, business associates in the D.A. Tompkins Company, filed incorporation papers for “The Atherton Mills,” Charlotte’s sixth cotton mill (Mecklenburg County, Record of Incorporations 1892). The factory location was just off South Boulevard at the south edge of Dilworth, a new streetcar suburb of Charlotte. The steam-powered mill, which drew its water from the old Summit Hill Gold Mine, was one of a host of new textile factories taking shape around the city at this time. At the end of July, 1892, the Charlotte Observer enthusiastically declared:

What other city in North Carolina can boast of starting two new factories in one week? The articles of incorporation of the ‘Atherton Mills’–the sixth factory–had scarcely been filed, before a seventh factory was [organized] and in the course of a few months there will be seven cotton factories in full operation in Charlotte. There’s no doubt about it, things are “humming” in the Queen City, and “humming” to the tune of lively progress (Charlotte Observer, July 21, 1892).

Tompkins, Miller and Smith, were New South entrepreneurs who were at the forefront of industrial development in Charlotte and the Piedmont. Miller (1856-1925), a graduate of Davidson College, was secretary-treasurer of the D.A. Tompkins Company, and later headed Charlotte’s tenth mill, the Elizabeth Cotton Mill (Huffman 1983; Morrill 1983). Smith (1862-1933) was a native of Baltimore who first came to Charlotte as sales representative for Thomas K. Carey and Son, an industrial supply firm in Baltimore. After 1901, Smith organized the Chadwick and Hoskins mills in Charlotte, and by 1907, was head of the Chadwick, Hoskins, Calvine (formerly Alpha), and Louise mills in and around Charlotte, and the Dover Cotton Mill in nearby Pineville, North Carolina. When these factories consolidated into the Chadwick-Hoskins Company in 1908, it was the largest textile firm in North Carolina (Huffman 1987; Morrill 1983).

Daniel Augustus Tompkins (1851-1914) played a particularly significant role in the development of the Piedmont textile industry. The son of an Edgefield, South Carolina planter, Tompkins studied engineering at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York. He arrived in Charlotte in 1883, as a representative of the Westinghouse Corporation, selling steam engines and machinery to the mills. In 1884, Tompkins launched his own business enterprise in Charlotte and began a remarkable career as one of the leading New South businessmen. In that year he organized the D.A. Tompkins Company, a machine shop and among the most influential contracting and consulting firms for the rising textile industry in the South. Glass (1992, 44) writes that this company was “at the forefront” of machinery manufacturing for the southern textile mills, offering mills “a local alternative to their dependence upon northern suppliers.”

D. A. Tompkins

Few locations have a prettier site than the Atherton Mills. The building is in the southern part of the city, just beyond the old fair ground, a few minutes walk off the car lines, and a short distance from the Charlotte, Columbia and Augusta Railroad, which has built a side track to the mill… The management of the business will devolve upon Mr. R.M. Miller, Jr., vice-president and treasurer. Mr. A.M. Price will be superintendent. The company has commenced the construction of the houses for operatives to live in, one cottage being already completed… There will be built twelve four-room houses, six three-room cottages and four two-room cottages (Charlotte Daily Observer, November 27, 1892).

The Atherton Cotton Mills complex developed steadily in the 1890s. Operations began in January, 1893, with 5,000 spindles manufacturing yarn goods. The floor space was equipped for expanding production, and by 1896, the mill housed machinery for 10,000 spindles. In that year, Atherton Mill employed about 300 operatives and included a mill village. This village comprised a school and 50 one-story, frame mill houses, situated along straight streets (mostly Euclid, Tremont, and Cleveland avenues) on the east side of South Boulevard. The village school, called the Atherton Lyceum, was a two-story, frame, multi-purpose facility that taught evening class in the basics of reading and writing and also housed a general store, town hall, and Sunday School classroom (Charlotte Daily Observer, November 17, 1896; April 3, 1897; Thompson 1926, 145; Hanchett 1986).

Atherton Lyceum

The mill complex was both typical of the textile-mill operations appearing throughout the Piedmont, as well as a model which Tompkins could describe in his books on mill construction and design (Glass 1978, 139-142, 147-148; Hall et al. 1987, 115-116; Crawford 1992). Some of the two, three, and four-room mill houses in the Atherton village were illustrated in Tompkins’ s book Cotton Mill: Commercial Features. The mill’s siting in a rural setting outside the city limits of Charlotte was also a common practice, which avoided local property taxes and helped control the activities of workers outside the mill (Tompkins 1899; Hanchett 1985; Glass 1992, 41-42).

In May, 1896, the Charlotte Daily Observer described the Atherton Cotton Mills as “situated in a beautiful oak grove in the southern suburb [Dilworth] of the city,” with mill housing “kept in good repair, neat and nicely painted.” The newspaper declared that “the product of the mill has an enviable reputation; it is well-known in all markets and one hears of it in the East, as much, possibly more so, than any other yarn mill in the South” (Charlotte Daily Observer, May 20,1896). Yet this glowing account obscures the sometimes harsh realities of working in the southern textile industry in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Work was often tedious and dangerous, and men, women, and children labored at low wages, 10 to 12 hours each weekday, and six hours on Saturday. And, while mill families achieved a measure of independence, life in the company-owned mill village was also largely regulated by mill owners and their supervisors. Guided by a combination of paternalism and pragmatism, owners sought to develop a stable and loyal work force by creating villages which were a tightly controlled and all-encompassing social system (Hall et al. 1987, 114-182). Newspaper accounts of injuries and fatalities at the Atherton Cotton Mills documented the perils of working in the textile factories. Through the years, reports appeared of picking room fires, mangled fingers, and even the death of an overseer, who was entangled in the steam-driven belts in the carding room (Charlotte Daily Observer, June 28, 1893; October 14, 1902).

The location of the Atherton Cotton Mills clearly reflected Charlotte’s emerging status as the hub of the Piedmont textile industry, as well as Dilworth’s role as an industrial as well as residential suburb. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Charlotte was transformed from being principally a trading town for local cotton farmers to a major textile center and symbol of the New South.

After the Civil War and the rebuilding and expansion of railroads in the South, leaders of the region began a drive for a New South based on manufacturing and urban growth rather than agriculture (Lefler and Newsome 1954, 474-489). The South’s new economic base was to rest largely on cotton textile production. The Piedmont region was particularly well suited for the textile industry, possessing a good supply of local capital, access to raw materials, good rail connections, and a great supply of labor drawn from nearby tenant farms and the Appalachian mountains (Mitchell 1921; Crawford 1992, 141). Charlotte’s central location in the region led to its rapid industrial growth. Between 1889 and 1908, 13 textile mills and a host of support industries appeared in the city or at its outskirts. As early as 1906, Charlotte boosters celebrated the fact that “within the radius of 100 miles of Charlotte, there are more than 300 cotton mills, containing over one-half the looms and spindles in the South” (Hanchett 1985, 70). By 1910, Charlotte had surpassed the port of Wilmington as the largest city in the state. By the 1920s, the Piedmont South had become the world’s preeminent textile manufacturing region, and Charlotte, boasted a local newspaper article, had become “unquestionably the center of the South’s textile manufacturing industry” (Charlotte Observer, October 28, 1928; Mitchell 1921). The city had become a major New South metropolis, with a population that had skyrocketed from approximately 7,000 in 1880, to over 82,000 by 1929, the largest urban population in the Carolinas (Sixteenth Census 1940).

The New South investors in Charlotte funded not only factories but also a ring of streetcar suburbs, which both reflected and contributed to the local prosperity. Dilworth, situated southeast of downtown Charlotte, was the first of these neighborhoods, beginning in 1891, the same week that trolley or electric streetcar service went into operation. Developed by the Charlotte Consolidated Construction Company (locally known as the Four Cs), whose president was Edward Dilworth Latta, the original Dilworth plan included not only residential streets and a recreational park, but also a factory district. A predecessor of the modern suburban industrial park, this district was located at the western edge of Dilworth, between South Boulevard and the Southern Railway (Morrill 1985, 302-303; Hanchett 1986; Oswald 1987). The first factory established in Dilworth, the Atherton Cotton Mills and its village provided the impetus for both industrial and residential development in the new suburb. Until Tompkins announced the construction of this textile factory complex, the sale of lots in the suburb had been slow, and the Four Cs was in financial peril. Writes Morrill (1985, 303), “[Tompkins’s] mill marked the beginning of the factory district that saved Dilworth from financial failure.” Within a few years this district also included such factories as the Charlotte Trouser Company, the Southern Card Clothing Company, the Charlotte Pipe and Foundry Company, a sash cord plant owned by O. A. Robbins, the Charlotte Shuttle Block Factory, and the Park Elevator Company, producers of pumps, heaters, and elevators (Morrill 1980; Morrill 1985, 302-304; Hanchett 1986) . In October, 1895, the Charlotte Daily Observer described Dilworth as “the Manchester of Charlotte,” and several months later the newspaper observed, “It does one good to go out to Dilworth and see the signs of prosperity and progress. The factories draw the people. Dilworth is beginning to be not only a social but an industrial center” (Charlotte Daily Observer October 23, 1895, January 31, 1896).

The corridor between South Boulevard and the railroad tracks continued to expand throughout the early twentieth century. By the 1920s, the district had also attracted not only the Parks-Cramer complex, but the Lance Packing Company, makers and distributors of snack-food crackers which occupied the 1300 block of South Boulevard, the Tompkins foundry and machine shop (located just north of Parks-Cramer), the Nebel Knitting Mill, the Hudson Silk Mill, a pipe and foundry plant, and assorted laundries, wholesalers, building suppliers, stores, and residences.

The first suburban fire station in Charlotte was located near the north end of the corridor, near Morehead Street, while just west of South Boulevard stood the Exposition Hall for the Made-in-the-Carolinas expositions, which were held during the 1920s to promote the industrial progress of the Carolinas (Miller’s Charlotte City Directory 1929; Bradbury 1992, 53-63). The Atherton Cotton Mills and the Dilworth industrial corridor thrived into the post-World War I years. In 1922, as part of the continuing process of consolidation of individual mills into chains of ownership or large corporations, the Atherton Cotton Mills was purchased by a group of Gaston County textile plant operators headed by John C. Rankin and S.M. Robinson, and reorganized as Atherton Mills, Inc. The Atherton corporate headquarters were also moved to Lowell, North Carolina, in Gaston County (Mecklenburg County, Record of Corporations 1922). The Dilworth industrial corridor began to lose factories by late 1920s and during the Great Depression, as firms shut down or started relocating to larger industrial tracts. In 1933, Atherton Mills, Inc. lost ownership of the South Boulevard plant in foreclosures on deeds of trust that occurred throughout the city. Vacant until 1937, the factory was then owned and operated until the early 1960s by J. Schoenith Company, Inc., manufacturer of “high grade” candy, baked goods, and peanut products. During the Schoenith tenure, a warehouse was constructed north of the mill, on the site of a cotton warehouse, and an office building was erected immediately east of the mill, facing South Boulevard. In recent years the main factory and warehouse have been used by wholesaling and textile-related manufacturing companies, and the former office building has been converted to a restaurant. More recently, the Atherton Mill has been converted into office and residential condominiums.

Notes

1 The authors wish to acknowledge the 1987 draft of the “Survey and Research Report on the Atherton Cotton Mill,” written by Dr. William H. Huffman and Nora Mae Black, and prepared in 1988 by Dr. Dan L Morrill. In particular, the present “Historical Sketch” is based largely on Huffman’s well-researched essay, and, upon consultation with the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission, is meant to be considered a final edition of that work. A copy of the draft report is available at the Historic Landmarks Commission, Charlotte, North Carolina.

References

Bradbury, Tom. Dilworth, The First 100 Years. Charlotte, N.C.: The Dilworth Community Development Association, 1992.

Charlotte Daily Observer (Charlotte, N.C.).

Clay, Howard Bunyan. “Daniel Augustus Tompkins: An American Bourbon.” Doctoral dissertation, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, 1950. Crawford, Margaret. “Earle S. Draper and the Company Town in the American South.” In The Company Town : Architecture and Society in the early Industrial Age. Ed. John S. Gamer. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992, 139-172.

Glass, Brent D. “Southern Mill Hills: Design in a Public Place.” In Carolina Dwelling: Towards Preservation of Place: In Celebration of the North Carolina Vernacular Landscape. Ed. Doug Swaim. Raleigh, N.C.: North Carolina State University School of Design, 1978, 138-149.

The Textile Industry in North Carolina, A History. Raleigh, N.C.: Division of Archives and History, North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, 1992.

Hall, Jacquelyn Dowd et al. Like A Family, The Making of a Southern Cotton Mill World. Chapel Hill, N.C.: The University of North Carolina Press.

Hanchett, Tbomas W. “Charlotte: Suburban Development in the Textile and Trade Center of the Carolinas.” In Early Twentieth-Century Suburbs in North Carolina. Eds., Catherine W. Bishir and Lawrence S. Early. Raleigh, N.C.: Division of Archives and History, North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, 1985, 68-76.

“Charlotte and Its Neighborhoods: The Growth of a New South City, 1850-1930.” Charlotte, N.C., 1986. (Typewritten.) Huffman, William H. “Survey and Research Report on the Atherton Cotton Mill.” Charlotte, N.C.: Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Properties Commission, 1988. Lefler, Hugh, and Albert Newsome. The History of a Southern State: North Carolina. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1954.

Mecklenburg County. Record of Corporations, Book A, p. 258.

Miller’s Official Charlotte, North Carolina City Directory. Asheville, N.C.: E. H. Miller, 1920,1929.

Mitchell, Broadus. The Rise of Cotton Mills in the South. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1921.

Morrill, Dan L “A Survey of Cotton Mills in Charlotte.” Charlotte, N.C.:Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Properties Commission, 1979. Survey and Research Report on the Park Manufacturing Company.” Charlotte, N.C.: Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Properties Commission, 1980.

“Survey and Research Report on the Atherton Mill House.” Charlotte, N.C.: Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Properties Commission, 1981.

“Edward Dilworth Latta and the Charlotte Consolidated Construction Company (1890-1925): Builders of a New South City. The North Carolina Historical Review. 62 (July 1985): 293-316.

Oswald, Virginia. “National Register Nomination for the Dilworth Historic District.” Raleigh, N.C.: Division of Archives and History, North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, 1987.

Smith, Doug. “Historic Mill to House Home Furnishing Center.” Charlotte Observer. February 8, 1993.

Thompson, Edgar T. Agricultural Mecklenburg and Industrial Charlotte, Chapel Hill, N.C.: The University of North Carolina Press, 1926.

Tompkins, D.A. Cotton Mill: Commercial Features. Charlotte, N.C.: Observer Printing House, 1899.

Sanbom Map Company. Charlotte, Mecklenburg County, North Carolina. 1929, 1946, 1953.

U. S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940. Population, vol. 1.

Winston, George T. A Builder of the New South: Being the Story of the Life Work of Daniel Augustus Tompkins. Garden City, New York: Doubleday, Page and Company, 1920.

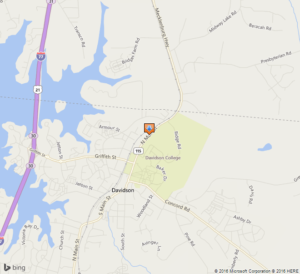

- Name and location of the property: The Armour-Adams House is located at 626 North Main Street in Davidson, North Carolina.

- Name, address, and telephone number of the present owner of the property: The present owners of the Armour-Adams House are

- David Sitton and Camilia Meador

626 North Main Street

Davidson, NC

Representative photographs of the property:

This report contains representative photographs of the property.

- A map depicting the location of the property: The following is a map of the location of the property. The UTM coordinates for the property are 17 514069E 3929184N.

- Current deed book references to the property: The most recent deed to this property is recorded in the Mecklenburg County Deed Book 15850, page 177-179. The tax parcel number of the property is 003-161-04.

- A brief historical sketch of the property: This report contains a brief historical sketch of the property.

- A brief architectural description of the property: This report contains a brief architectural description of the property by Stewart Gray.

- Documentation of why and in what ways the property meets the criteria set forth in NCGS 160A-400: Special significance in terms of historical, architectural, and/or cultural importance:

The Commission judges that the property known as the Armour-Adams House does possess special historic significance for Charlotte-Mecklenburg. The Commission bases its judgment on the following criteria:

- The Armour-Adams House is representative of the evolution of the built environment of Davidson in terms of the emergence of the town’s merchant class.

- The Armour-Adams house is a locally distinctive example of the Folk Victorian style of architecture that was made possible by innovations in technology and transportation, and retains a high degree of integrity.

- The Armour-Adams House was the long-time home of Margaret H. Adams, a beloved first grade teacher for decades at the Davidson Elementary School.

- Integrity of design, setting, workmanship, materials, feeling and/or association.

The Commission judges that the architectural description included in this report demonstrates that the property known as the Armour-Adams House meets this criterion.

- Ad Valorem Tax Appraisal: The current assessed value of the property is $321,000 ($156,300 building; $162,500 land). The property is zoned residential.

This report was prepared by Jane Starnes and revised by Dr. Dan Morrill and Jennifer Payne.

Date of Report: 24 April, 2006

A Brief Historical Sketch of the Property

The Armour-Adams House, built circa 1900 by Davidson merchant Holt Armour, can best be understood within the context of the evolution of the built environment of Davidson, North Carolina. The two-story, Folk Victorian style dwelling, which faces west on North Main Street, is representative of the shift in Northern Mecklenburg County during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries from an agrarian tradition to a way of life that was increasingly rooted in commerce and industry. In Davidson, this change was facilitated by the establishment of Davidson College, and was strengthened by the reactivation of the railroad in 1874. One of the many results of these forces was the emergence of a diverse commercial class in Davidson, of which Holt Armour was a member. In addition, Davidson is a community that has been historically committed to education, and the Armour-Adams house served as the home of a long-time Davidson teacher who was a part of the movement to bring quality education to the children of Davidson.

Prior to the foundation of Davidson College in 1835, the area surrounding Davidson was rural, fertile farmland.[1] Farmers such as Robert Armour lived and worked on large swaths of land. The Armours, whose association with the region dates to as early as the 1820s, acquired holdings that stretched “along North Main Street as far south as the cemetery” and “extended westward beyond the railroad and eastward over the area where Davidson College dormitories and Patterson Court now stand.”[2]

The traditional, agricultural life that families like the Armours lived for generations began to be altered in 1835, when a group of Presbyterians chose the spot as the location of their second attempt at providing higher education imbued with Presbyterian values to the youth of the region. The result of this decision was Davidson College, envisioned as a manual labor institution, and named for William Davidson, who died at the Battle of Cowan’s Ford in the Revolutionary War.[3] The construction of the first College buildings followed; and when Davidson College opened its doors in 1837, several edifices had been constructed for the purposes of housing, educating, and supporting student life. Twelve buildings had been erected on campus by the close of the antebellum period, including the Chapel, five dormitory rows (of which Elm Row and Oak Row alone still stand), Tammany Hall ( a faculty residence destroyed in 1906), the Old Chambers Building (destroyed by fire in 1921), and the President’s House.[4]

The College drew new residents to the town, some from the surrounding rural environs and some who were associated with the faculty and student populations of the school. The re-activation of the railroad in 1874 quickened the pace of the town’s growth, and established the community as the commercial center of northern Mecklenburg County. Residents like the Armour family, who had lived and worked on the land for generations, were drawn to the thriving town in search of new forms of employment in the fledgling merchant class that provided goods and services to the growing population of the town, but whose fortunes were not directly linked to the everyday operations of the College.

The earliest of the Davidson’s merchants was Thomas Sparrow, who operated the first in a long tradition of boarding houses in Davidson.[5] The Helper Hotel, or Carolina Inn, as it is alternatively known, was established in the 1850s by Lewis Dinkins as a store that provided goods to the College population, and was expanded and reestablished as a hotel in the 1860s by Hanson Helper.[6] The commercial sector of Davidson was augmented in 1890, with the construction of the Delburg Cotton Mill, followed in 1908 by the addition of the Linden Cotton Mill. By 1910, Davidson, once a relatively isolated college town, had grown into a thriving commercial and industrial center. Holt Armour took advantage of these circumstances in 1912, when he established Armour Brothers and Thompson, a general retail store that operated out of the brick structure that still stands on the north corner of Brady’s Alley.[7] Armour Brothers and Thompson was one of several local retail and service firms that operated on the North Main Street commercial corridor, and which also included Goodrum and Company, the White Drug Store, the Jetton Drug Store, and the general merchandise firm of Knox and Brown.[8] The commercial district that was established by 1920, and which included the Armour Brothers and Thompson store, retains much of the same character that is evident on North Main Street today, because it was hemmed in to the east by the College, to the north and south by residential development, and to the west by the railroad.[9]

The distinctive Armour-Adams House was erected on a lot that Holt Armour received from his father, Robert Armour, in 1899.[10] Constructed in the popular Folk Victorian style, the Armour Adams House stands as a testament to the innovations in transportation and technology that made the style possible. The movement stemmed from the Victorian-era architectural forms, such as Queen Anne, that were popular in the last decades of the nineteenth century, in combination with the simple and widespread National or vernacular styles that brought more highly stylized dwellings into the reach of the middle class.[11] The advent of the railroads made lumber and machinery more accessible; the use of manufactured nails replaced the hewn joints which required skilled labor. The mechanical jigsaw and lathe were two of the most important innovations which aided the growth of this style, and Queen Anne-like scrollwork and brackets, as well as turned porch supports, which were previously only accessible to a few, were now within the realm of possibility for the masses.[12]

In 1919, Holt Armour purchased from his sister, Margaret Armour, the lot adjoining 626 North Main Street to the north. He sold the original home to J. Hope Adams, who moved with his two adult children to Davidson from York, South Carolina. The Adams family became longtime residents of the town, and J. Hope’ son, Albert, served as mayor from 1931 to 1933.[13]

- Hope’s daughter, Margaret Adams, was a part of the movement in the town to provide a quality education to the town’s children. Just as the Presbyterians were responsible for bringing higher education to Davidson, they were also the force behind the primary education movement for some of the town’s children. Public instruction in Davidson from 1835 until the 1890s was initially reliant upon individual citizens who operated schools out of their homes or buildings provided by the community for the purpose of education. However, by the turn of the century, a movement was well under way to provide a consistent public education to the white children of the town. The cause of public education was spearheaded by the trustees of Davidson College, who in 1892 established the Davidson Academy, which was initially located in the Masonic Hall near the intersection of South Street and South Main Street. The new schoolhouse, which stood on the site of the present Davidson IB Middle School, was completed in 1893 and expanded in 1924.[14] Unfortunately, in a pattern that was familiar to the older residents of Davidson, the expanded school was destroyed by fire in 1946, and classes were held in the gymnasium and in the basement of the Presbyterian Church. Its replacement, which serves today as the Davidson IB Middle School, was completed in 1948.[15] Margaret Adams was a part of the early growth of Davidson education in the twentieth century. She taught generations of first grade students in Davidson from 1930 until her retirement, and is remembered in town as a “diminutive and greatly loved teacher.”[16]

The Armour-Adams House is an illustration of the evolution of the Town of Davidson from the turn of the twentieth century until the present day. Its earliest inhabitant, Holt Armour, was a part of the shift from an agrarian tradition to a town life that was centered on commerce and industry and that was facilitated by the establishment of Davidson College and by the reactivation of the railroad. In its architectural style, the home is evidence of the effect that changes in transportation and technology had on middle class citizens and their ability to build stylized dwellings. Finally, in its connection to Margaret Adams, the home retains a link to the Presbyterian fervor for quality education for the town’s citizens.

[1] Mary D. Beaty, Davidson: A History of the town from1835 to 1927 (Davidson: Briarpatch Press, 1979), 3. Information in this report is taken largely from an initial survey and research report prepared by by Jane Starnes in December, 2005, and from Jennifer Payne and Dr. Dan L. Morrill, “ The Evolution of the Built Environment of Davidson, NC,” available at http://www.cmhpf.org/surveydavidsonpayne.htm.

[2] Ibid., 15.

[3] Cornelia Rebekah Shaw, Davidson College (New York: Fleming H. Revell Press, 1923), 7-16.

[4] Beaty, A History of the Town, 181.

[5] Ibid., 11.

[6] Payne and Morrill.

[7] Beaty, 82.

[8] Starnes; Beaty, 180.

[9] Beaty, 134.

[10] Starnes.

[11] Virginia and Lee McAlester, A Field Guide to American Houses ( New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1984), 310.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Starnes.

[14] Beaty, 64, 171.

[15] Kristin Stakel and Dr. Dan L. Morrill, “Survey and Research Report on the Davidson IB Middle School,” December, 2005; Beaty, 64.

[16] Ibid., 82.

Architectural Description

The Armour-Adams House is a very well preserved example of late Queen Anne Style architecture. While more restrained in terms of ornamentation than many earlier Queen Anne Style houses, the Armour-Adams House demonstrates the asymmetrical massing and machine-made woodwork typical of the style. In addition, the house is situated in a prominent position on North Main Street. The house has retained a high degree of integrity in terms of its appearance and historic building material.

The house sits close to the sidewalk of North Main Street in Davidson and is setback about 40’ from the street, as are most of the neighboring houses. The house faces west on a lot that slopes down towards the rear of the lot.

The one-and-one-half-story frame house is notable for its asymmetrical massing, and its various roof profiles. One of the house’s prominent features is the one-story wrap-around hipped-roof porch. Unlike the typical pier supports found on many early-twentieth-century house, the porch of the Armour-Adams House is supported a continuous single-wythe curtain wall. Turned post support the porch roof, and are decorated with sawn brackets. Low guardrails connect the posts, and feature turned balusters and a moulded handrail. The porch follows the contour of the house, and projects out from a three-sided projecting bay. The porch is accessed by non-original brick steps. A small gable, featuring a recessed triangular panel, is located over the porch entrance.

Behind the porch, the façade is dominated by a projecting gabled bay that contrasts with a taller hip roof that covers the principal section of the house. The house is three bays wide. A doorway is centered between the three-sided projecting bay on the southern side of the façade, and a single window to the north. The tall windows appear to be original one-over-one double-hung units, with louvered shutters. The façade has retained its original three-panel two-light door. In contrast to the turned woodwork, the fenestration is surrounded with simple trim. All of the exterior walls are covered with simple weatherboard accented with moulded corner boards.

Above the porch, the front gable is pierced with a single narrow double-hung window. The gable is accented with wide and moulded barge and soffit boards, as well as gable returns. Located over the front entrance is a hipped dormer with two swing-in single-light casements with screens decorated with sawn-work. Moulded trim and a wide freeze-board separates the dormer’s siding from the soffit. With the exception of the porch, the house is covered with metal shingles decorated with a fish-scale pattern. Two interior chimneys pierce the roof the northern chimney features a corbelled band, and a corbelled flared top. The southern chimney is plain and of more recent construction.

South Elevation

The south elevation of the original house is only two bays deep, with just two windows piercing the wall. The wrap-around porch extends over only a part of the elevation. A hipped dormer, like the one on the front of the house, is located on the south side of the house. Like the south elevation, the north elevation is simple in comparison with the façade. Just two bays wide with a single window in the north-facing gable, the north elevation demonstrates the brick-pier construction of the foundation, the wide water table, and wide freeze board. An original one-room-deep gabled rear wing is setback slightly from the north elevation.

Front Elevation

Rear Elevation

The rear elevation is the most altered part of the largely original house. A single six-over-six is centered in the rear wall of the rear wing. A similar window is located in the gable. A shed roof extends from south side of the rear wing, and may have once been a porch. An enclosed porch extends from the rear of the hipped-roof principal section of the house. A recent deck is located on the rear of the house. A narrow hipped dormer with a single window is roughly centered over the principal section of the house.