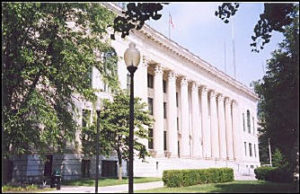

THE MERCHANTS AND FARMERS NATIONAL BANK BUILDING

Click here to view photo gallery of the Merchants and Farmers National Bank Building.

1. Name and location of the property: The property known as the Merchants and Farmers National Bank Building is located at 123 East Trade Street, in Charlotte, North Carolina.

2. Name, address, and telephone number of the present owner of the property:

The present owner and occupant of the property is:

Mr. Robert T. Glenn

123 E. Trade Street

Charlotte, NC 28202

Telephone: (704)375-5549 (business)

3. Representative photographs of the property: This report contains representative photographs of the property.

4. A map depicting the location of the property: This report contains a map which depicts the location of the property.

5. Current Deed Book Reference to the property: The most recent deed to this property is listed in Mecklenburg County Deed Book 4447 at page 552. The Tax Parcel Numbers of the property are: 080-012-12 and 080-012-13.

6. A brief historical sketch of the property: This report contains a brief historical sketch of the property prepared by Mrs. Janette Thomas Greenwood.

7. A brief architectural description of the property: This report contains an architectural description of the property prepared by Thomas W. Hanchett.

8. Documentation of why and in what ways the property meets the criteria set forth in N.C.G.S. 160A-399.4:

a. Special significance in terms of its history, architecture, and/or cultural importance: The Commission judges that the property known as the Merchants and Farmers National Bank Building does possess special significance in terms of Charlotte-Mecklenburg. The Commission bases its judgment on the following considerations: 1) the Merchants and Farmers National Bank Building, erected in 1871-72, is the oldest commercial building in the central business district of Charlotte; 2) the Merchants and Farmers National Bank Building possesses iron trim which was manufactured by the Mecklenburg Iron Works, an enterprise of regional importance; 3) the front facade of the Merchants and Farmers National Bank Building is one of the finer local examples of the Italianate style; 4) the Merchants and Farmers National Bank Building served as headquarters for that financial institution from 1872-1921; 5) the third floor of the Merchants and Farmers National Bank Building was an Odd Fellows Hall for many years.

b. Integrity of design, setting, workmanship, materials, feeling and/or association: The Commission contends that the attached architectural description by Mr. Thomas W. Hanchett demonstrates that the Merchants and Farmers National Bank Building meets this criterion.

9. Ad Valorem Tax Appraisal: The Commission is aware that designation would allow the owner to apply for an automatic deferral of 50% of the Ad Valorem taxes on all or any portion of the property which becomes “historic property.” The current appraised value of the .084 acres of land is $87,600. The current appraised value of the building is $11,050. The total current appraised value is $98,650. The property is zoned B3.

Date of Preparation of this Report: February 1, 1983

Prepared by: Dr. Dan L. Morrill, Director

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Properties Commission

218 N. Tryon Street

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

Telephone: (704) 376-9115

The Civil War brought about the end of an era in North Carolina banking history. Every bank in the state failed when the federal government imposed a 10% tax on bank notes soon after the war ended in 1865.1 However, Charlotte soon had a national bank, The First National Bank of Charlotte, which opened in August 1865. Four years later a state bank, The Bank of Mecklenburg, opened for business.2 The Merchants and Farmers National Bank was Charlotte’s second national bank, and the city’s third bank since the Civil War. It was organized in January 1871 and officially chartered by the Federal government of February 1, 1871.3 The original officers of the bank were Clement Dowd, president, J. Harvey Wilson, vice president, and Archibald McLean, cashier. Dodd, a member of a prominent Moore County family, left his hometown of Carthage after the Civil War to join his old army Zebulon B. Vance, North Carolina’s war governor, in a law practice in Charlotte.4 Dowd quickly rose to prominence in the community; in the last quarter of the century he was considered to be one of Charlotte’s most influential men, J. Harvey Wilson was a lawyer in a practice with his son. The board of directors was made up of Wilson, Allen Macauley, James H. Carson, William J. Yates, Thomas H. Brem, S.P. Smith and R.M. Miller. Most were local businessmen; Macauley was a cotton buyer and Brem was a partner in a dry goods business. In addition, Brem served on the first board of directors of the First National Bank of Charlotte. Miller was a wholesale dealer in flour and provisions. Yates was editor of a local newspaper and Smith was a lawyer.5

The Charlotte Democrat welcomed the city’s new bank, and asserted, “The large and growing business of Charlotte affords ample room for suing all the Banking capital that can be secured by the city.”6 The establishment of a second national bank in Charlotte less than six years after the Civil War ended reflects the city’s rapid growth in the Reconstruction era. Instead of quashing economic and industrial enterprise, the postwar years brought rampant growth. Charlotte escaped the war relatively unscathed. Thousands of people took refuge in Charlotte to escape Sherman’s army and many of them stayed on. By 1871, Charlotte’s population was 5-6000 people, nearly quadruple its Civil War size of 1500 people. Charlotte’s position on a number of rail lines enhanced its growth and it soon became a “cotton center.”7

“Up to, and even to the close of the late war, the commercial interests of Charlotte were of much smaller significance than they are now. Ten years of trade, which has poured into her lap since the last gun was fired on the 24th of April, 1865, has added materially to the wealth, influence, prosperity, and prospects of the City of Charlotte.”8

Merchants and Farmers Bank, hoping to take advantage of Charlotte’s remarkable growth, first operated in the Springs Building on the corner of N. Tryon and E. Trade Streets, the business axis of Charlotte.9 An indication of the bank’s immediate success is a notice published six months after it opened announcing “a dividend of 4 percent declared by Board of Directors, payable on and after 10th July, 1871.”10 This was the same dividend offered by the six year old First National Bank. By September 1871, the board of directors announced an increase in stock by $50,000.11 Finally, in December, 1871, the bank offered a 5% semi-annual dividend.

In June of 1871, the directors of the Merchants and Farmers Bank purchased a lot in the first block of East Trade Street from R.M. and Ellen Oates, L.W. and Harriet Saunders, and D.W. and Anna Oates, at a cost of $5,000.00.13 Construction of a new banking house was started soon after. The new bank, which originally had a pressed iron front, one of many constructed in Charlotte that year,14 was a source of pride for Charlotteans, and was a symbol of industrial rebirth in Reconstruction North Carolina. The Charlotte Democrat remarked,

“The Iron columns for the new building of the Merchants and Farmers National Bank on Trade St., are as fine as anything of the kind ever brought from the North. There is no further necessity of sending North for such work. It can be done here.”

The Democrat explained that “the iron fronts for the new buildings now being erected were cast at the Foundry of Capt. John Wilkes in this city.”15 Wilkes owned and operated the Mecklenburg County Iron Works on East Trade St., which housed the Confederate Naval Yard from 1862-65. Merchants and Farmers opened its new building around February 1872. In late January the Democrat reported, “The three story iron front building for the Merchants and Farmers National Bank is about completed and business will be transacted therein hereafter.”16 Around the time the new banking house opened, the Augusta Chronicle took note of the Merchants and Farmers Bank in an article entitled, “Trip to Charlotte, NC,” which the Charlotte Democrat reprinted. Charlotte, the Chronicle noted, was “a live and progressive city…rapidly looming into distinction as one of the leading commercial and railroad centers of the South.” The city “possesses ample banking facilities,” with three banks, “aggregating $1,000,000 or more of capital.” The Chronicle continued:

“The Merchants and Farmers Bank is a new institution having having been in operation only about a year. It has a paid up capital of $200,000, is well-officered, and enjoys a liberal share of public patronage and confidence. Its organization is mainly due to the public spirited efforts of T.H. Brem, R.M. Miller, A. Macauley, and S.P. Smith. The banking house of the company is a handsome new three-story brick building finished in elegant style on the interior.”

Thomas H. Brem rose to the presidency of the bank in 1874 when Clement Dowd became president of the Commercial National Bank, Charlotte’s third national bank.18 Brem served as president until 1879. Charlotte added another bank, in addition to Commercial National, by 1875, Farmer’s Savings Bank. Both Commercial and Farmer’s were located on East Trade Street. The Bank of Mecklenburg had its offices on Tryon between Trade and Fourth.19 Thus, an early banking district emerged around East Trade Street with Merchants and Farmers at the center of activity. For the next forty years, from the 1870s through 1910, Merchants and Farmers was Charlotte’s second largest bank, second only to First National. The 1879 City Directory reported First National with $400,000 of capital; Merchants and Farmers had $200,000 of capital.20 That same year druggist J.H. McAden was elected president. McAden, who ran a pharmacy on Independence Square, served longer than any other president, from 1879 through 1904. By 1896, the City Directory reported that the banking capital of Charlotte “is by far the largest in the state, the sum total which, including surplus, is $1,243,500.”21 By 1910, Merchants and Farmers slipped to fourth place in capital behind American Trust Co., Commercial National, and First National.22

That year, Merchants and Farmers reported a total of $340,000 in assets. George E. Wilson, a prominent Charlotte lawyer, took over as president. In 1904 and served through 1918. W.C. Wilkinson took over in 1918 and served through 1933.23 In addition to housing the Merchants and Farmers National Bank in this period, the building at 123 East Trade Street served as a meeting place for fraternal and civic organizations. The third floor was an Odd Fellows Hall. The Independent Order of Odd Fellows, Mecklenburg Declaration Lodge #9, the city’s oldest Odd Fellows lodge, met at “Odd Fellows Hall over Merchants and Farmers Bank” from 1875 through 1914.24 Charlotte Lodge #88, IOOF, met there from 1918 through 1920. The Catawba River Encampment #21 IOOF used the hall in 1879 and 80. From 1904 through 1914, the Rosalie Lodge #22, Daughters of Rebekah, an IOOF women’s organization, met at the hall as well.25 Many other organizations used the IOOF hall, including the Mecklenburg Literary Society, the North Carolina Scotch-Irish Society, the Carpenters and Joiners Union’ and The Improved Order of Heptasophs. The YMCA used the hall “over the Merchants and Farmers Back”. in 1879/80, before its own hall was built on S. Tryon Street.26 In addition, offices were available for organizations. Charlotte’s first Chamber of Commerce, the forerunner of the Greater Charlotte Club, and the present day Chamber of Commerce had offices in the bank building in 1889.27 In 1921, Merchants and Farmers National Bank moved to a new location, 5 West Trade Street. From 1921 through 1934, the bank rented its old building to two businesses. From 192l-24, the U.S. Fidelity and Guaranty Co. of Baltimore occupied the building. Askin’s Clothing rented from Merchants and Farmers from 1925-34.28

The demise of Merchants and Farmers took place in March of 1933 when President Franklin D. Roosevelt declared a “bank holiday.” All banks in North Carolina were closed and by March 18, the state banking commissioner allowed those with sufficient funds to reopen, a total of 222 banks. The Merchants and Farmers Bank was not among these, one of many bank casualties in the spring of 1933. On February 1, 1934, J. A. Stokes, as conservator of the Merchants and Farmers Bank, and “vested with all rights, powers, and privileges now possessed by receivers of insolvent banks, sold the property at 123 E. Trade Street to Fred Y. and Florence B. Bradshaw of Charlotte for $35,000.30 The Bradshaws continued to rent the building to the current tenant, Askin’s Clothing, until 1939. The building was vacant in 1940. Bradshaw Millinery, owned and operated by Fred Y. Bradshaw, occupied the building from 1941-1952. From 1953 through 1972, Belk’s Children’s Shoes Annex rented the structure.31 On September 30, 1974, North Carolina National Bank, the executor of Fred Y. Bradshaw’s estate, sold the property to Sidney and Tena Levin of Cocoa Beach, FL.32 The Levins rented the building to The Shoe Mart, which had rented the building since 1973. The Levins sold the property on July 3, 1981 to Robert T. Glenn of Charlotte, who continues to rent the building to The Shoe Mart.33 Glenn is interested in preserving the structure.

NOTES

1 T. Harry Gatton, “Banking History in North Carolina: The Story of Creative Enterprise,” The Tar Heel Banker, September, 1981, p.20.

2 Charlotte City Directory, 1875/76.

3 Charlotte Democrat, Jan. 24, 1871, p.3; February 7, 1871, p.3.

4 “Dowd Family,” Vertical Files, Carolina Room, Public Library of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County.

5 Charlotte City Directory, 1875/76.

6 Charlotte Democrat, January 24, 1871, p.3.

7 History of Charlotte. Charlotte City Directory, 1875/76.

8 Ibid.

9 Charlotte Democrat, February 7, 1871, p.3.

10 Ibid., July 4, 1871, p.3

11 Ibid., September 26, 1871, p.3.

12 Ibid., December 23, 1871, p.3.

13 Mecklenburg County Deed Book 11, p.38.

14 The Charlotte Democrat reported an “iron front” buildings going up in Charlotte in the winter of 1871/72, including Brown and Brem’s store on E. Trade St. and Mr. Joseph Henderson’s 2 story store.

15 Charlotte Democrat, October 10, 1871, p.3.

16 Ibid., January 23, 1872, p.3.

17 Ibid., March 12, 1872, p.2.

18 Charlotte City Directory, 1875/76.

19 Ibid.

20 Ibid., 1879.

21 Ibid.,1896.

22 Ibid.,1913.

23 Ibid.,1904, Lyle, 1933.

24 Ibid.,1875-1914.

25 Ibid.,1904-1914.

26 Ibid.,1879/80.

27 Ibid.,1889.

28 Ibid.,1921-34.

29 Gatton, “Banking History,” p.22.

30 Mecklenburg City Deed Book p.349, p. 281.

31 Charlotte City Directory, 1941-1972.

31 Mecklenburg County Deed Book 3711, p. 281.

32 Ibid., Book 4447/552.

The 1871 Merchants and Farmers National Bank Building is a three story brick loft structure in the heart of the business district of Charlotte, North Carolina, the oldest commercial building in the central city. Its stuccoed front is decorated in the Italianate style with iron trim manufactured by the Mecklenburg Iron Works, believed to be the oldest surviving example of locally produced architectural ironwork. Though changes have been made to the first story over the years, the upper facade is in excellent original condition and the second and third floors of the interior retain much period trim, including fireplace mantels In addition, the third floor walls are painted with mystic symbols of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows Lodges which met there from the 1870s through 1920. The front of the Merchants and Farmers Bank is a flat-stuccoed wall pierced by three windows on the second floor and three on the third. To this flat wall is applied iron decoration. At the top is a sheet iron cornice with modillion brackets between heavy end blocks. Cast iron quoins define the two sides of the facade. Windows are tall and narrow double-hung one-over-one pane sash. They have cast iron lintels at the top and cast iron sills at the bottom.

Originally the first floor shopfront had five square cast iron columns topped by a sheet iron cornice. Like the rest of the building’s ironwork, the columns were cast at the nearby Mecklenburg Iron Works. This shopfront is now gone, replaced by glass show windows that curve in to a recessed entry. The shopfront appears to date from the early 1950s, probably part of remodeling done when Belk’s children’s shoe shop moved into the structure in 1953. Behind the facade the Bank is a simple three story brick structure with a flat roof. Side walls butt against the adjoining buildings and have no windows. Between 1900 and 1905, according to Sanborn Insurance maps, a large two story brick addition was made at the rear, nearly doubling the building’s size. It has one-over-one pane double-hung windows set in arched openings, unlike the flat-topped six-over-six pane windows at the back of the original structure. Inside, the first floor of the building appears to date from the same early 1950s remodeling that produced the shopfront. At one time the stairs from the second floor came down to a door opening onto the street. In the remodeling this stairway, inside the original building along the east side wall, was removed to add retail space and new stairs were built in an old airshaft running along the side of the rear addition. Both the second and third floors, vacant for many years, remain much as they were in the nineteenth century.

The second floor is made up of one large room and a bathroom in the addition and three rooms in the original building. These consist of a large room across the front of the building, a small glassed-in office across the middle, and a medium sized room across the back. Along the east wall of the front room is a wood and glass partition that originally surrounded the stairwell to the street. Wood and glass doors open from the old landing into the front room, the office, and the back room. Along the west wall of the second floor are three fireplaces, all of which retain their mantels. Two are in the front room, one in the back. The front and back fireplaces were evidentially converted to gas at one time, for they contain curved cast iron inserts. All three fireplace openings have been closed up. Besides the mantels, second floor trim consists of wooden molding around the windows and doors, and a high wooden baseboard topped by molding. Mid-twentieth century electric light fixtures of milky white glass hang from the ceiling, an Art Deco touch probably from the 1953 remodeling. The staircase to the third floor runs up the east wall toward the rear of the building, rising from the old landing. At the top of it is the third floor with two rooms. The rear room has a small enclosed toilet at the back west corner with the remains of an overhead flush tank and a wooden sink. Next to it on the west wall is the building’s only open fireplace, brick-hearthed but now missing its mantel.

From the back room two glass-transomed doorways open onto the IOOF Lodge Hall. Each has a four-panel mortise-and-tenon door, with the panels surrounded by raised molding. Each door has a peephole associated with lodge rites. The Lodge Hall occupies the front two-thirds of the floor, a large room approximately twice as deep as it is wide. It is lit by three tall windows looking onto the street. Two small pipes protruding from the ceiling indicate the room once had gas lights. A heavy molded chair rail showing traces of gold paint runs around the room. A bright metal picture molding runs around the room about four feet below the high ceiling. The west wall has traces of only one fireplace, now closed up and lacking its mantel, compared with two fireplaces in the same area on the second floor. Partially revealed beneath peeling wallpaper is the Lodge Hall’s most striking feature. The plaster walls are painted red with lodge symbols starkly painted in black and white. Visible are a pair of angels with arms crossed on breasts, an hourglass, an all-seeing eye, a row of numerals, a sun, and a skull and cross bones. The symbols are evenly spaced five to six feet apart on the east and west walls of the Hall, about ten feet from the floor so as to command the viewer to look up.