This report was written on March 7, 1988

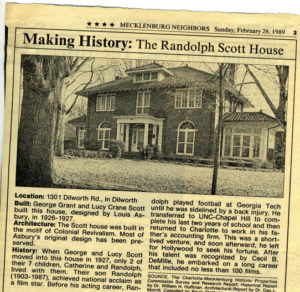

1. Name and location of the property: The property known as the Randolph Scott House is located at 1301 Dilworth Road in Charlotte, North Carolina.

2. Name, address, and telephone number of the present owner of the property: The owner of the property is:

Mr. and Mrs. James A. Haynes

1301 Dilworth Road

Charlotte, NC, 28203

Telephone: (704) 375-3313

3. Representative photographs of the property: This report contains representative photographs of the property.

4. A map depicting the location of the property: This report contains a map which depicts the location of the property.

5. Current Deed Book Reference to the property: The most recent reference to this property is recorded in Mecklenburg Deed Book 5203, page 437. The Tax Parcel Number of the property is: 123-102-01.

6. A brief historical sketch of the property: This report contains a brief historical sketch of the property prepared by Dr. William H. Huffman, Ph.D.

7. A brief architectural description of the property: This report contains a brief architectural description of the property prepared by Dr. Dan L. Morrill, Ph.D.

8. Documentation of why and in what ways the property meets the criteria for designation set forth in NCG.S. 160A-399.4:

a. Special significance in terms of its history, architecture, and/or cultural importance: The Commission judges that the property known as the Randolph Scott House does possess special significance in terms of Charlotte-Mecklenburg. The Commission bases its judgment on the following considerations: 1) the Randolph Scott House, erected in 1926-1927, was briefly the home of Randolph Scott (1903-1987), noted cinema actor; 2) George Grant Scott (1867-1936), the initial owner, was an influential resident of Charlotte, including representing Fourth Ward on the Board of Aldermen; 3) the Randolph Scott House was designed by Louis H. Asbury (1877-1975), an architect of local and regional significance; and 4) the Randolph Scott House occupies a strategic location in terms of the townscape of Dilworth, Charlotte’s initial streetcar suburb.

b. Integrity of design, setting, workmanship, materials, feeling, and/or association: The Commission contends that the architectural description by Dr. Dan L. Morrill, Ph.D. which is included in this report demonstrates that the Randolph Scott House meets this criterion.

9. Ad Valorem Tax Appraisal: The Commission is aware that designation would allow the owner to apply for an automatic deferral of 50% of the Ad Valorem taxes on all or any portion of the property which becomes “historic property.” The current appraised value of the improvement is $163,540. The current appraised value of the .537 acres of land is $60,000. The total appraised value of the property is $223,540. The property is zoned R9.

Date of Preparation of this Report: March 7, 1988

Prepared by: Dr. Dan L. Morrill

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Properties Commission

1225 S. Caldwell St.

Charlotte, NC 28203

Telephone: (704) 376-9115

Dr. William H. Huffman

The Scott House was built in 1926-27 by George Grant and Lucy Crane Scott, and was designed by the noted Charlotte architect Louis Asbury. The Scotts were the parents of film star Randolph Scott, who lived in the house as a young man and returned for frequent visits after achieving stardom. Local lore has it that Randolph built the house for his mother and sister, but in fact it was built by his parents before he started his film career.

George G. Scott (1867-1936) was born in Norfolk, VA of Quaker parents, and was educated at Guilford College and West Town Friends school in Western Pennsylvania. In 1891, he and Lucy Lavinia Crane, of Charleston, WV, were married. In the 1890s, Scott set up a public accountant firm in Charlotte, and in 1907 was elected to a term on the Board of Aldermen from Fourth Ward. As Chairman of the Finance Committee, he oversaw the city’s first published financial statement, and modernized the accounting systems of the administration and waterworks departments. His statewide reputation resulted in his drafting of North Carolina’s first certified public accountant law, and he was appointed by the governor to the state board of accountancy, which he chaired for a number of years. Recognized as an expert in accounting procedures and income tax law, Scott was a frequent contributor to accounting journals. By the 1920s, his firm, Scott, Charnley & Co., had offices in Brevard Court in Charlotte, as well as branch offices in Greensboro, Raleigh and Columbia. 1

Lucy Crane Scott (1866-1958) was born in Luray, VA, in the Shenandoah Valley, the daughter of Col. Joseph Minor Crane and the former Barbara Lavinia Lineberger, and attended Hollins College in Roanoke, VA. Mrs. Scott was very interested in her heritage, and belonged to the D. A. R., the Magna Carta Society, the Plantagenet Society (the membership to which she willed to her daughter Barbara) and the Knights of the Order of the Garter. The Scotts had seven children: Luciele (Mrs. T. T. Perry), Margaret (Peggy), Catherine Strother, Sarah Virginia, Barbara, George Randolph, and Joseph Crane. At the time of her death at the age of 92, Mrs. Scott had fourteen grandchildren and sixteen great-grandchildren. 2

For many years, the Scotts lived on 10th Street in Fourth Ward, in a large Victorian House that is no longer extant. In 1923, however, they took an interest in moving to Charlotte’s first streetcar suburb, Dilworth, by investing five thousand dollars in a lot on Dilworth Road, which they bought from the Charlotte Consolidated Construction Company (commonly Known as the 4 C’s).3 The 4 C’s was a development company founded by Edward Dilworth Latta (1851-1925) and five associates in l890. In 1893, Latta, a Princeton-educated South Carolina native, had built a trouser manufacturing plant in Charlotte that prospered. He and other entrepreneurs of the city were convinced of the great potential for growth in the wake of New South industrialization, based on cotton mill production and distribution that took off in Charlotte in the 1880s, and sought to capitalize on that growth. 4

Thus the 4 C’s bought a 422-acre farmland site on the southwest edge of town and began to promote the sale of lots in 1891. To entice potential buyers out to the suburb, they built a new electric trolley line that ran from the Square into and around the new development, which included its attractive park Latta Park was at the heart of the development, and it boasted a pond for boating, an outdoor pavilion that hosted traveling shows, and strolling pathways. The development was designed to have a true mix of housing, with the fine houses located on the main boulevards and more modest dwellings on the side streets. 5

In October, 1925, when the Scotts were ready to move ahead with building their Dilworth Road house, they selected the versatile local architect Louis Asbury to do the design. Asbury (1877-1975) was the city’s first professionally-trained architect. A Charlotte native who used to help his father build houses in the city as a youth in the 1890s, he attended Trinity College (now Duke University), and completed his architecture studies at MIT. After gaining practical experience with some architectural firms in New York, Asbury returned in Charlotte in 1908 to begin a nearly fifty-year career in the city. Of the more that one thousand designs that came from his studio, many are landmarks in Charlotte and surrounding towns. In Charlotte, they include the old County Courthouse, the C. P. Moody and Jamison houses on Providence Road, the McAden House on Granville, the Myers Park Methodist Church, the Law Building, the Hawthorne Lane Methodist Church, the Garibaldi-Bruns facade at the Square, and numerous other institutional, church and private home designs. 6

By January, 1926, the design was complete, and local builder Thies-Smith Realty Co. took out a building permit, and estimated the cost of construction to be $25,000.7 The next year, the house, with its distinctive dual stairway with spiral rails that ascends from the front entry, was finished, and the Scotts moved into their fine new ten-room home. By this time, only Catherine and Randolph lived at home. Randolph (1903-1987) had attended private college-prep schools, and went to Georgia Tech, where he played football and dreamed of becoming an all-American. After a back injury ended his football career, he transferred to UNC-Chapel Hill for his last two years, then returned to Charlotte to work in his father’s firm. But business did not interest the restless young man, so, in 1928, he set off for Hollywood with best friend Jack Heath and a letter of introduction to Howard Hughes from his father. After getting a bit part from Hughes and coming to the attention of Cecile B. DeMille, (who sent him to the Pasadena Playhouse for two years to get acting experience), Randolph Scott launched a long acting career that included some one hundred films. Tall, slim, and handsome, he embodied the American ideal of the hero in the same way as Charles Lindbergh, and enshrined that image in many classic westerns. His visits to Charlotte to see his family and friends were often an occasion for stories in the local press. 8

George G. Scott died unexpectedly in Raleigh in 1936, and Lucy Crane Scott lived in the house until her own death in 1958. Two years later, it was sold to Frank O. Alford, whose heirs sold the house to the present owners, James and Ellen Haynes, in 1986.9 The Haynes have restored the house and grounds in a sensitive way that allows the architecture and the setting to stand out once again.

NOTES

1 Charlotte Observer ,March 5, 1935, p. 1; ‘Charlotte Builders,’ undated Charlotte Observer article on file in Public Library.

2 Charlotte Observer, June 25, 1958, p. 1B.

3Deed Book 526, p. 88.

4 Dan L. Morrill, “Edward Dilworth Latta and the Charlotte Consolidated Construction Company (1890-1925); Builders of a New South City,” The North Carolina Historical Review, 62 (July, 1985), 293-316; Thomas W. Hanchett, “Charlotte Neighborhood Survey,” Charlotte, Mecklenburg Historic Properties Commission, 1984.

5 Ibid.

6 Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Louis Asbury Papers. Architectural Job List, 1629, 13 October 1925; information on file at the Charlotte Mecklenburg Historic Properties Commission.

7 City of Charlotte Building Permit dated 5 January 1926.

8 Interview with Virginia Heath, Matthews, NC 22 June 1987.

9 Deed Book 2132, p. 129; Deed Book 5203, p. 437.

|

|

Louis Asbury |

Dr. Dan L. Morrill

The Scott House, a two and one-half story, three bay wide by two bay deep, running bond brick dwelling with a tiled tripped roof, plain external end chimneys, a one story enclosed sunroom on either end of the main block, a centered tripped dormer, and broad eaves with decorated exposed rafter ends, was erected in 1926-27 for George Grant Scott and Lucy Crane Scott, the parents of film star Randolph Scott.1 It was designed by Louis H. Asbury (1877-1975), an architect of local and regional importance.2 The Scott House has experienced alterations over the years, most notably with the enclosure of a porch (now sunroom) on the left end of the main block, the modernization of the kitchen, and the placement of a table in what is now a breakfast room. The overall integrity of Asbury’s design survives, however.

The Scott House belongs to a broad and diverse category of so-called “period houses” which were erected in the affluent suburbs of early twentieth-century North Carolina.3 Situated on a tree-shaded lot at the corner of Dilworth Road and Arosa Avenue in the curvilinear section of Dilworth, Charlotte’s first streetcar suburb, the house is inspired primarily by the decorative vocabulary of Colonial Revivalism.4 Colonial Revivalism, which emphasizes classical ornamentation, geometric massing and, at least in North Carolina, simplicity of detail in comparison with the more adventuresome specimens of this motif found in the major cities of the North and Midwest, was probably the most popular example of historic eclecticism which emerged in the late 1800s and early 1900s in the United States, including the South. This widespread acclaim was in no small part due to the fact that Colonial Revivalism provided compelling images which enabled wealthy suburbanites to satisfy their “search for order” and their desire to live in an “idyllic escape from the overcrowding, crime, and ethnic strife identified with the city.”5

Its Colonial Revival details notwithstanding, such as its columned entrance portico, entrance door with sidelights and fanlight with tracery, semi-circular voussoirs with keystones above fanlights atop the double doors on the side bays of the front facade, and smaller fanlights on the enclosed sunrooms, the Scott House, like many of Louis Asbury’s early houses, also exhibits qualities of the Rectilinear style, especially in the box-like severity of its overall form and massing.6 Particularly noteworthy in this regard are the second floor windows, which are quite simple, almost bungaloid, in appearance.

Again, in keeping with many of Asbury’s other house designs, the Scott House is more purely Colonial Revival on the inside, even emulating the restrained elegance associated with the Federal style. A spacious entrance hallway leads to a pair of graceful, dramatic stairways which rise to a landing and then delicately join to continue to the second floor. Large, fluted Ionic columns and pilasters with egg and dart moulding, and an exquisite but essentially unencumbered cornice adorn the wide passageways that open from the entrance hallway to the living room, on the left, and the dining room, on the right, each of which contains a fireplace with a Colonial Revival mantelpiece.

An especially striking feature of the Scott House, and one which demonstrates Louis Asbury’s skill and flare as an architect, is the interface between the stairwell and the second floor hallway. Situated to allow the morning sunlight to pour through double doors with a fanlight above, the space creates a feeling of being suspended in air. A balustrade with thin pickets borders the landing and then sweeps with compelling and dramatic impact to the stairway and then suddenly downward.

The garage, an original outbuilding, is located on the southeastern corner of the property. Mimicking the main house, it is a running bond brick structure with a tiled tripped roof, side windows, and three large entrance doors. The landscaping of the house is quite elegant. A low, rock rubble wall extends across the front, and a metal and brick wall extends along the northern or Arosa Avenue side of the property and encloses a portion of the backyard. A serpentine walkway extends from the Dilworth Road sidewalk to the front portico. The property contains several large trees. Finally, the Scott House occupies a strategic location in terms of the overall Dilworth townscape, because it is the first residence on the southern side of Dilworth Road as one travels south from Morehead Street; and it is also situated immediately across Arosa Avenue from the parking lot for Covenant Presbyterian Church.

NOTES

1 Dr. William H. Huffman, “Historical Sketch of the Scott House” for the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Properties Commission (June, 1987).

2 For additional information on Louis H. Asbury, see “Survey and Research Report on the Old Advent Christian Church” for the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Properties Commission (November 2, 1987); Thomas W. Hanchett, “Charlotte And Its Neighborhoods: The Growth of a New South City, 1850-1930” for the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Properties Commission (1986), hereinafter cited as Hanchett.

3 For a detailed analysis of the architecture of North Carolina’s early twentieth century suburbs, see Catherine W. Bishir and Lawrence S. Early, Early Twentieth-Century Suburbs in North Carolina: Essays on History, Architecture and Planning (Raleigh: Archeology and Historic Preservation Section, Division of Archives and History, North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, 1985), hereinafter cited as Suburbs. For an explanation of the term “period house”, see John Poppeliers, S. Allen Chambers, and Nancy B. Schwartz, “What Style Is It? Part Four.” Historic Preservation (January-March, 1977), pp. 14-23.

4 The Colonial Revival style arose in the 1880s and is attributed to the architectural firm McKim, Mead and White (Charles Follen McKim, W. R. Mead, Stanford White). For additional information, see Marcus Whiffen, American Architecture Since 1780: A Guide to the Styles (Cambridge: M.l.T. Press, 1969), pp.159-165. In Charlotte, the Colonial Revival style, called initially the “true classical style”, was introduced in 1894, by Charles Christian Hook (1869-1938), the first architect who resided in Charlotte throughout his career ( Charlotte Observer, September 19, 1894). For a history of the evolution of Dilworth, see Dan L. Morrill, “Edward Dilworth Latta and the Charlotte Consolidated Construction Company (1890-1925): Builders of a New South City” The North Carolina Historical Review (July, 1985), pp. 293-3167. For a comprehensive analysis of the built environment of Dilworth, see Thomas W. Hanchett, “Charlotte And Its Neighborhoods” for the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Properties Commission (March 1985) Chapter 5.

5 Bishir, “Introduction”, Suburbs. David R. Goldfield,” North Carolina’s Early Twentieth-Century Suburbs and the Urbanizing South”, Suburbs, p. 9. Margaret Supplee Smith, “The American Idyll in North Carolina’s First Suburbs: Landscape and Architecture”, Suburbs, p. 23.

6 Hanchett. The term “Rectilinear” was coined by Wilbert R. Hasbrouk and Paul E. Sprague in A Survey of Historic Architecture: the Village of Oak Park, Illinois (Oak Park, Illinois: Landmarks Commission, Village of Oak Park, 1976), pp. 8-14, 16-19. Most approximating the Scott House among Louis Asbury’s houses in Charlotte are the J. M. Jamison House (1912), the Charles Philo Moody House (1913), and the Henry M. McAden House (1917-1918).