This report was written on November 20, 1998

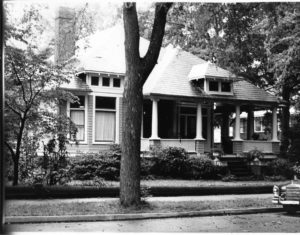

1. Name and location of the property: The property known as the S. Bryce McLaughlin House is located at 2027 Greenway Avenue in Charlotte, North Carolina.

2. Name, address and telephone number of the present owner of the property: The present owners of the property are:

Munro B. & Belva H. Sefcik

2027 Greenway Avenue

Charlotte, NC 28204

3. Representative photographs of the property: This report contains representative black and white photographs of the property. Color slides are available at the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission office.

4. Maps depicting the location of the property: This report contains three maps depicting the location of the property.

5. Current deed book reference to the property: The most recent deed to this property is recorded in Mecklenburg County Deed Book 7483 on page 827. The tax parcel number of the property is #127-046-09.

6. A brief historical sketch of the property: This report contains a brief historical sketch of the property.

7. A brief architectural description of the property: This report contains a brief architectural background and a physical description of the property.

8. Documentation of why and in what ways the property meets criteria for designation set forth in N. C. G. S. 160A-400.5:

a. Special significance in terms of its history, architecture, and/or cultural importance: The Commission judges that the property known as the S. Bryce McLaughlin House does possess special significance in terms of Charlotte-Mecklenburg. The Commission bases its judgment on the following considerations:

1) The S. Bryce McLaughlin House was built by S. Bryce and Bertha Dotger McLaughlin in 1911 on a portion her family’s land. It is the only remaining historic structure associated with the Dotger farm, which stretched between Caswell Road and Briar Creek.

2) The S. Bryce McLaughlin House predates, and is therefore the earliest house in, the Rosemont section of Charlotte’s historic Elizabeth neighborhood.

3) The S. Bryce McLaughlin House, a one and one-half story shingled bungalow, is a genuine Craftsman House and a good example of the style. It was built from a plan that was published in 1908 in The Craftsman magazine, and is thus the product of the legendary furniture designer and architect Gustav Stickley. There are no other known Stickley designs among the designated Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks.

b. Integrity of design, setting, workmanship, materials, feeling and/or association: The Commission contends that the physical and architectural description which is included in this report demonstrates that the S. Bryce McLaughlin House meets this criteria.

9. Ad Valorem tax appraisal: The Commission is aware that designation would allow the owner to apply for an automatic deferral of 50% of the Ad Valorem taxes on all or any portion of the property which becomes a designated “historic landmark.” The current total appraised value of the improvements is $ 182,200. The current total appraised value of the lot is $ 80,000. The current total value is $ 262,200. The property is zoned R-5.

10. Portion of the property recommended for designation: The interior and exterior of the S. Bryce McLaughlin House and its lot are currently being considered for designation.

Date of preparation of this report: November 20, 1998

Prepared by: Mary Beth Gatza

P. O. Box 5261

Charlotte, NC 28299

(704) 331 9660

Historical Significance

The S. Bryce McLaughlin House was built in 1911 by S. Bryce and Bertha Dotger McLaughlin on a portion of the Dotger farm. At the time, it was sited to face what is now called Caswell Road. During the mid-1910s, the house was picked up and turned around to face Greenway Avenue, which was still undeveloped at the time. It is the earliest house in the Rosemont section of Charlotte’s Elizabeth neighborhood, and is the only remaining residence associated historically with the Dotger farm (which stretched from Caswell Road to Briar Creek).

Land History

At the turn of the twentieth century, the land surrounding downtown Charlotte was overwhelmingly rural. Andrew J. Dotger owned a farm where the Rosemont section of Elizabeth now stands. Andrew Dotger was originally from the Philadelphia, Pennsylvania area, and ultimately returned to the northeast. During his stay in Mecklenburg, however, he purchased three tracts on Monroe Road in the 1890s.1 Together they totaled 89 acres and included an old plantation house on Monroe Road.2 It is unknown whether Andrew Dotger ever resided in the house, but what is known is that by 1899, he had left Charlotte and settled in Essex County in northern New Jersey.3

“Because of my love and affection,” Andrew J. Dotger granted a life estate4 to his brother, Henry C. Dotger (1862-1936), Henry’s wife, Bertha M. Dotger (1861-1932), and their heirs. In the deed, Andrew stated that Henry, Bertha and their survivors “may occupy and use the said plantation as a home” rent free (provided they pay the taxes) “as long as they…may elect to live upon the said place.”5 Andrew’s gift of tenure to his brother was not without conditions. Andrew was specific on a number of points, as follows: 1) The title to the land would transfer to the children of Henry and Bertha Dotger upon their deaths 2) “No partition of said land nor any sale thereof shall be made…until the youngest child shall arrive at the age of twenty-one years…” 3) “Upon my death…the title to the said land shell vest in the executor of my will to be held by him…” In making these stipulations, Andrew effectively prevented Henry from controlling the future disposition of the property.6

By the first decade of the twentieth century, Charlotte’s urban development pressed outward, inching closer and closer to the Dotger Farm. Dilworth, Charlotte’s first suburb, had opened in 1891, and various other neighborhoods around town experienced their genesis within the next two decades. Four of the five developments which make up the neighborhood now called Elizabeth were started in the decade surrounding the turn of the century. They are: Highland Park (Elizabeth Avenue), 1897; Piedmont Park (Sunnyside Avenue, Central Avenue), 1900; Oakhurst (Bay Street, Hawthorne Lane), 1903; and Elizabeth Heights (East Eighth Street, Clement Avenue), 1904.7 The fifth and final section, Rosemont, was yet to be.

In 1907, the boundaries of the burgeoning city of Charlotte were extended in all directions, greatly enlarging the size of the city. To the southeast, the city line now came right up to Henry’s side yard (near present-day Ridgeway Avenue), and included a portion of the Dotger land. Henry, no doubt, was aware of the development opportunities and the potential for profit therein. Due to the terms of the life estate, however, Henry’s ability to sell the land was restricted, forcing him to petition the courts for permission to subdivide. The Mecklenburg Superior Court ruled in January 1912 that the land could indeed be sold. The court order reads, in part, that “the interest of all parties concerned would be materially enhanced if the lands…were sold…”8 Purchase offers were already pending for three tracts in 1912. One offer was from S. Bryce McLaughlin for .45 acres near what was then described as the intersection of East Sixth Street and Old Monroe Road (now Greenway Avenue and Caswell Road).9

The deed to the McLaughlin property was not in fact delivered until 1915. The reason for this delay is unclear. A court document dated October 1915 authorizes again the sale of “the said property to the said Bertha Dotger McLaughlin, wife of S. Bryce McLaughlin…” This document mentions that “the said lot has a residence upon it of the value of about $5000.00 which was erected…by the said S. Bryce McLaughlin at his own cost and expense with the understanding…that a deed to said lot would be made to him or his said wife at a fair price when the same could be done legally…” The deed was finally executed on October 20, 1915, to a home that the McLaughlins had lived in for four years.10

Later sections of this same court document address the lots and houses of two of Bertha’s sisters. Freda L. (Mrs. A. W.) Burch and Anna C. (Mrs. W. C.) Kirby both had homes on East Seventh Street that they desired legal title to. In both sections, the legal language and the description of the house is the same as for the McLaughlin House. In both cases, the court ordered the sales–for the Burch House in 1919 and for the Kirby House in 1920.11 Neither house is still standing.

Rosemont Company

The Rosemont Company incorporated on February 20, 1915. 1,250 shares of stock were authorized, valued at $100 each (total $125,000). There were seven original stockholders, who divided 500 shares unequally among themselves. They were: George W. Watts (200 shares); G. C. White (100 shares); C. B. Bryant (50 shares); Cameron Morrison (50 shares); W. S. Lee (34 shares); Z. V. Taylor (33 shares); and E. C. Marshall (33 shares). The Rosemont Company was empowered to do the following:

1) buy and sell land

2) lay out lots, block and streets

3) own, construct, sell or lease buildings

4) buy and sell their capital stock

5) enter into contracts

6) issue bonds

No doubt the Rosemont Company was created specifically in order to develop the Dotger farm, because they purchased the remainder of the Dotger tract in March of 1915, and made no other major purchases. Since they paid $110,000 for the land, they apparently were able to sell more shares or otherwise raise capital quickly.12

Developing the Dotger tract took the Rosemont Company a good six years. The earliest plat on file in the Mecklenburg County courthouse is dated May 1921.13 By then the development was officially named “Rosemont.” The map is labeled as a revised plat, implying that an earlier plan existed. Research done in the 1980s states that a map was drawn in 1913 and another in 1916. The 1916 plat, which has never been found, was reportedly drawn by noted landscape architect John Nolen,14 who designed Independence Park (1905) on East Seventh Street and was chief planner of the Myers Park neighborhood (1911). Earliest lot sales in Rosemont, as listed in the deed indexes, were in March of 1921.15

Greenway Avenue was created in the 1910s. The first mention of it in the city directories is in 1916, at which time it was named as the address for the S. Bryce McLaughlin House. Although the house had been standing since 1911, it had originally faced Monroe Road (now Caswell Street). It was moved sometime between 1914 and 1916–it was reportedly lifted and rotated on its site to face the new and as-yet-undeveloped Greenway Avenue. No other houses show up in the city directories on Greenway Avenue until 1923/24, at which time seventeen addresses were listed. Thus, the S. Bryce McLaughlin House stood alone facing Greenway between the time it was moved in the mid-1910s and 1923–almost ten years.

Henry Dotger Family

Henry Casper Dotger (1862-1936) was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on September 12, 1862. It was there, presumably, that he met and in 1884 married another Philadelphian, Bertha Marie Shutt (1861-1932). They arrived in Charlotte in the 1890s and by 1899 were settled on the Monroe Road tract of land Dotger’s brother owned. Henry worked the land as a dairy farm and raised his family there. Four of the Dotger’s five children made the move to Charlotte with their parents, the youngest child was born here. The children were: Freda (1885-1973), Anna (1887-1953), Frederick (1888-1969), Bertha (1886-1919) and Dorothy (1901-1989).16 Fred became a dairy farmer in his own right, leaving the family land but remaining in Mecklenburg County. All four daughters attended Elizabeth College in Charlotte. At that time, the college was located at the end of Elizabeth Avenue at Hawthorne Lane (now Presbyterian Hospital), and thus was within walking distance for the girls.17

Freda Dotger (1885-1973) was married twice–first in 1908 to Albert Waterman Burch (1861-1924), and second to Charles R. Nisbet (1871-1943) in 1931. Together A. W. and Freda had two daughters, and built and lived in a house (no longer standing) on East Seventh Street and Caswell Avenue.18

Anna Dotger (1887-1953) was well-educated–she attended Swarthmore College and Columbia University before returning to Charlotte to teach at Elizabeth College. She married William C. Kirby (1872-1967), and they built and resided in a home next to her sister, Freda, on East Seventh Street near Caswell Avenue. This house is no longer standing. Anna and William Kirby had three children, a son and two daughters.19

Dorothy (1901-1989), the youngest daughter, achieved success as a professional golfer. She married Richard Thigpen, and had three children with him.20 Together they resided in the Dotger farmhouse after the death of Henry and Bertha Dotger.

Bertha Dotger (1886-1919) chose for her husband Samuel Bryce McLaughlin (1886-1969). They were wed “on the lovely green in front of her father’s house” on May 24, 1911. The “beautiful setting” was “redolent with the fragrance of honeysuckle and magnolia;” the ceremony itself was “marked with charming simplicity.” At the time, the bride was described as “cultured and charming,” “gifted with beauty of face and grace” and “exceedingly popular.” After the “elegant reception” at her parent’s house, the couple departed for their honeymoon to three northern cities–New York, Philadelphia and Washington, DC.21

In preparation for their life together, Bryce and Bertha built a house in 1911 on her family’s land. Their wedding announcement in the Charlotte News mentioned that after their honeymoon “they will occupy their pretty new bungalow near the Dotger home.”22 Bryce and Bertha built from a plan that had been published in The Craftsman magazine in December 1908. They sited the house facing, yet well back from, what was then called Monroe Road (now Caswell Road). Just a few years later, in the mid-1910s, they turned the house to face what was to become Greenway Avenue.

S. Bryce McLaughlin Family

S. Bryce McLaughlin was the son of Margaret Gillespie and John B. McLaughlin (1855-1937). J. B. McLaughlin served as alderman for the city of Charlotte for fourteen years, and as chairman of the board of county commissioners for four years. Bryce was well-educated–he attended Baird School for Boys, Brown University, Davidson College, and Erskine College. Upon the occasion of his marriage, it was said of Bryce that he was “of Mecklenburg traditions and inherits with them the characteristics of his forebears–high integrity, honor, strong convictions and close adherence to principle.”23 Years later, his daughter would describe him as “a wonderful man,” “stately,” “dignified,” and very “knowledgeable.” She remembers him as “loving” and extremely kind to others.24

As a young man, Bryce McLaughlin worked in his father’s store, Cochrane & McLaughlin Company, on College Street. Bryce was listed in the city directories at various times as salesman, bookkeeper or manager. At some point, he shifted careers and went into real estate loans and insurance. He is known to have worked for the Federal Land Bank (Columbia, SC) from 1917-1919, and for the State and City Bank and Trust Company (Richmond, VA) from 1922-1924.25 Although it involved much travel away from his family, McLaughlin stayed in this line of work for many years. He employed a housekeeper who lived in the house and helped look after the children.26 Bryce McLaughlin died at home in 1969 at the age of 83.

Bryce and Bertha McLaughlin had three children: S. Bryce, Jr. (1914-1921), Harry (1916-1989) and Bertha (b. 1919). Bryce died at age seven of spinal meningitis. Harry graduated from Davidson College in 1938, fought in World War II, worked for the post office, and served as a church elder. He lived in Waxhaw at the time of his death in 1989.27 Daughter Bertha eventually married and moved away. Young Bertha never knew her mother, because, tragically, Bertha, Sr. died only hours after giving birth to her only daughter.

Bertha’s death on February 12, 1919, at age 28, was sudden and unexplained. The newspaper reported that it “was a shock to scores of friends.” She was described as “delightful in personality and possessing of the love and esteem of many friends.” Her obituary further noted that “she loved the home life and was a devoted mother.”28

Bryce McLaughlin mourned the loss of both his eldest son and his wife. Eventually, though, he got remarried to Miss Anne Graham Kyle (1895-1973). They were wed on April 15, 1927 at her father’s home near Lynchburg, Virginia. She reportedly hailed “from families widely known in this section of Virginia” and was a graduate of Agnes Scott College in Decatur, Georgia.29

After graduating from college in 1917, Anne relocated to Richmond, Virginia, where she worked for the YWCA in 1917 and 1918. She then moved to Charlotte, where she remained in the employ of the YWCA from 1918-1921. She was active in the Daughters of the American Revolution both here and in Virginia. She died on May 6, 1973.30

After the death of Anne McLaughlin, the S. Bryce McLaughlin House passed to Bryce’s surviving children, Harry and Bertha, who sold the property in 1973. It passed through a succession of owners between 1973 and 1993 when it was purchased by the current owners.

Gustav Stickley

Gustav Stickley (1858-1942) was one of eleven children born on a farm in Wisconsin to Leopold and Barbara Stoeckel. The family moved to Pennsylvania in 1874 or 1875, and there Gustav began the first phase of his career–making furniture. For the next decade and a half, Stickley produced and sold wooden furniture, working at times with various partners, including an uncle and a brother.31 From these inauspicious beginnings, Stickley would parlay his interest and experience in furniture design into an historic empire. Within two short decades, the name Gustav Stickley would become synonymous with the Craftsman Movement, which had a major impact on early-twentieth century furniture, decorative arts, textile design and architecture.

Arts & Crafts Movement

By the end of the century, Stickley had developed an active interest in the Arts & Crafts Movement, which had enjoyed a steady following in England since the 1860s. Proponents of the Arts & Crafts Movement argued for a departure from the fussy, mass-produced, and often poor-quality objects that were abundant during the Victorian era. They desired, instead, a more prideful, professional approach to the decorative arts, such as was found in the medieval crafts guilds.

After a trip to Great Britain in 1898, Stickley expressed the design ideals and philosophy of the Arts & Crafts Movement through his furniture. He abandoned the standard ornate Victorian motifs and constructed furniture that was simple, robust and straightforward. His designs were unique and represented a complete departure from all that was popular at the time. “Craftsman” was the name he gave to his style, though it is sometimes generically referred to as mission furniture. Stickley stamped or labeled each piece with his own maker’s mark–a drawing of a medieval joiner’s compass and the motto “Als ik kan” (as I can).

The Craftsman

In 1901, Stickley created a magazine with a dual purpose–to preach the Arts & Crafts philosophies and to market his own furniture. The premier issue of The Craftsman appeared on October 1, 1901. The magazine was widely distributed and proved to be immensely popular. During its fifteen-year run, The Crafstman magazine featured articles on many diverse topics, but always retained its focus on Arts & Crafts ideals. The magazine was so influential that eventually the Arts & Crafts Movement came to be called the Craftsman Movement.

It was only natural that Stickley’s interest in home furnishings would expand to include architectural design. In August of 1902, the first house plan appeared in the pages of The Craftsman magazine. In mid-1903, he hired two professional architects, Ernest G. W. Dietrich (1857-1924) and Harvey Ellis (1852-1904), and published plans in the magazine for the first of many “Craftsman Houses.” In November of 1903, The Craftsman readers saw the introduction of the Homebuilder’s Club. In this program, subscribers could order any published house plan free of charge. The Homebuilder’s Club was so successful that it remained active for the remainder of the magazine’s run. Stickley boasted in 1915 that over $20 million dollars worth of Craftsman homes had been built that year across the United States and in such far-flung places as Fiji.32

Craftsman Houses

At the turn of the century, a brand-new house type, called a bungalow, was on the horizon. The bungalow represented a radical change from Victorian architecture not just stylistically, but also functionally. It was anticipated that the modern twentieth-century family would not rely as heavily on domestic servants, and would lead a less formal lifestyle than their parents did. Voices of progressive reformers, feminists and home economists were all calling for a new, modern, efficient home environment. Bungalows were thus streamlined and designed to make housework simpler and easier. This was achieved, in part, by building smaller houses with fewer, larger rooms and by opening up floor plans. Architects strove to minimize clutter and dust-catching surfaces. They dispensed with elaborate moldings and woodwork, and reduced the need for free-standing furniture by incorporating built-ins (bookcases, cabinets, seating, dressers, etc.). This new approach to domestic architecture fit nicely with the Arts & Crafts ethic, and Stickley quickly gravitated toward it.

The bungalow aesthetic included simple lines, low-pitched gable roofs, engaged porches (where the porch is sheltered by the main roof, with no change in pitch), dormers and grouped windows. Honest, natural materials were favored, especially wood, brick and uncut stone. Architects were not afraid to show construction details, like exposed roof rafter ends on the outside and boxed ceiling beans on the inside. Design lines were kept simple–straight lines and clean surfaces.

Stickley’s Craftsman houses, like his furniture, focused on strength and simplicity. He made full use of the bungalow vocabulary, and yet created plans with his own unique style. Believing that the hearth was the center of the home, Stickley’s plans featured predominant fireplaces, and he included fireside inglenooks wherever possible. Stickley’s hallmark was interior woodwork, virtually always stained in a dark finish. His designs included liberal use of door and window trim, hardwood floors, wainscoting, ceiling beams, staircases, and built-in furniture. He always drew clean, simple lines. The overall effect was richness without fussiness.

Stickley’s mating of the Arts & Crafts idiom with the bungalow house type was a success. He was not the first or only architect using the bungalow house type or the Arts & Crafts style. Stickley was, however, the most influential, since it was he who disseminated the Craftsman House across America. Through The Craftsman magazine, he brought his unique style to the forefront by giving it wide distribution. Never before had an architectural style been popularized in such a manner.

PHYSICAL DESCRIPTION

Architectural Significance

The S. Bryce McLaughlin House has architectural significance as a good example of a genuine Craftsman House with exceptional integrity. The one and one-half story wood-shingled bungalow was built in 1911 following plans printed three years earlier in The Craftsman magazine. The plan was published by Gustav Stickley, whose influential magazine, The Craftsman, popularized his unique Craftsman House style and ultimately spawned an empire revolving around Stickley’s own designs in architecture, furniture and decorative arts.

S. Bryce McLaughlin House

S. Bryce McLaughlin based his modern new home on a plan that first appeared in The Craftsman magazine in December of 1908. It was described there as “a roomy, inviting farmhouse, designed for pleasant home life in the country.”33 Some minor modifications were made to the plan–namely McLaughlin’s choice to eliminate a fourth bedroom upstairs and to use the big room on the first floor (originally planned as a kitchen) for living space and build a smaller kitchen next to it, in an area that had been planned as an outside kitchen. He also opted to reverse the plan, flopping it so the entry would be on the right instead of the left. Otherwise, the S. Bryce McLaughlin House is identical to the published plan.

The house is a one and one-half story bungalow with a low-pitched, side-gabled roof. A full-width front porch shields the entire facade, and is composed of a broad shed roof supported by tapered, square wood columns. Windows throughout the house are four-over-one double-hung sash, placed in groups. The facade wears two sets of two windows and a group of three windows. A very broad shed dormer pierces the roofline and holds similar grouped windows–two sets of two and a group of three. Exposed roof rafter ends delineate the eave line all around the house. The entry is located in the right (east) bay of the facade and features a wide, glazed front door. The exterior of the house is clad with wood shingles. There is a wide, brick exterior end chimney with gently sloping shoulders on the east side elevation.

The only modification to the exterior of the house in its eighty-seven year history is the enclosing of a screened porch on the left rear (northwest) corner. This was accomplished by using wood-shingled walls and one-over-one double-hung sash windows of a similar size and shape to the original. As a result, the alteration blends almost seamlessly with the original fabric.

On the interior, Stickley’s trademark emphasis on dark-stained woodwork is apparent. Every surface in the living room is trimmed in dark woodwork–the floors are hardwood, the ceiling in beamed, the walls are sheathed with board-and-batten wainscot. The same dark trim surrounds the doors and windows, including the panelled pocket doors to the dining room.

Dining Room

Built-In Window Seat

The central focus, of the room, however, is the fireplace inglenook at the left (east) end of the room. Here Stickley placed a brick fireplace in an alcove and surrounded it with built-in benches, creating a cozy, intimate space. Stickley favored enclosed stairways in his Craftsman Houses, and that inclination is seen here. The stair begins in the living room, takes a quarter-turn and rises up through the wall cavity to the second floor. There is no newel post or balustrade, but instead the stringer (the side piece of the staircase) extends upward high enough to function as a railing.

The second floor holds three rooms and a bath. Originally, there were three bedrooms, but the wall between the center room and the hallway was removed by previous owners. It is still a distinct room, but is now open to the stairway. The characteristic dark wood found downstairs is also repeated on the second floor in the panelled doors and trim. In the bathroom, the original clawfoot tub is still in place.

A few alterations have taken place on the interior since the house was built in 1911. They include: the addition of a few closets and a second bathroom; the removal of a wall on the second floor; and a kitchen remodeling. Virtually no original material has been removed.

A two-car garage stands to the rear of the lot (northwest corner). It is a rectangular frame building with a front-gabled roof and is covered with German siding. It is not thought to have been built at the same time as the house (1911), since it is positioned relative to the current, and not the original, siting. It is, however, thought to date from the repositioning of the house in the mid-1910s, and should therefore be considered contemporary with the house.

Notes

1 Mecklenburg County Deed Book 104, page 122; Mecklenburg County Deed Book 110, page 306; Mecklenburg County Deed Book 134, page 497.

2 In current terms, the Dotger house was located on East Seventh Street between Ridgeway and Laurel Avenues. Demolished in the 1960s, it is now the site of the Carolina Eye Associates building.

3 Mecklenburg County Deed Book 134, page 497.

4 A life estate is an arrangement where the first party gives the second party the legal right to occupy the property for the remainder of the second party’s life, without actually transferring legal ownership to the second party.

5 Mecklenburg County Deed Book 134, page 497; Mecklenburg Superior Court Civil Minute Book 18, page 175.

6 Mecklenburg Superior Court Minute Book 18, page 175; Mecklenburg County Deed Book 134, page 497.

7 Thomas W. Hanchett, “Charlotte and Its Neighborhoods: The Growth of a New South City, 1850-1930” (draft manuscript for the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Properties Commission, 1985), pp. 5-11.

8 Mecklenburg Superior Court Minute Book 18, pages 174-78.

9 One offer was from the Sisters of Mercy for five and one-third acres (most likely the site of the present-day Mercy Hospital), and another was from a W. L. Nicholson for 1.87 acres on East Seventh Street.

10 Mecklenburg Superior Court Minute Book 24, page 75; Mecklenburg County Deed Book 351, page 188.

11 Mecklenburg Superior Court Minute Book 24, pages 75-77.

12 Mecklenburg County Records of Corporation, Book 4, pages 270-71; Mecklenburg County Deed Book 337, page 455.

13 Mecklenburg County Map Book 322, page 230.

14 Hanchett, “Charlotte and Its Neighborhoods” (draft), pp. 20-21.; Black & Black, “Elizabeth Historic District National Register Nomination,” p. 8.7.

15 Mecklenburg County Grantor Index, 1919-1936.

16 The Charlotte News, 11 October 1936, p. 1B; The Charlotte Observer, 11 October 1936, p. 1; The Charlotte Observer, 10 September 1932, p. 7; The Charlotte News, 1 January 1970, p. 4A.

17 Interview with Bertha McLaughlin Johnson, 25 October 1998.

18 The Charlotte Observer, 5 November 1924, p. 1; The Charlotte Observer, 6 June 1943, sec. 2, p. 1.

19 The Charlotte News, 19 October 1967, p. 8A.

20 The Charlotte Observer, 5 October 1989, p. 9B.

21 The Charlotte News, 25 May 1911, p. 2.

22 The Charlotte News, 25 May 1911, p. 2.

23 The Charlotte News, 25 May 1911, p. 2, The Charlotte News, 6 September 1969, p. 3A.

24 Interview with Bertha McLaughlin (Mrs. Grant) Johnson, 25 October 1998.

25 Charlotte City Directories, various years; The Charlotte News, 6 September 1969, p. 3A.

26 Johnson interview, 25 October 1998.

27 The Charlotte Observer, 3 June 1989, p. 12A.

28 The Charlotte Observer, 13 February 1919, p. 5.

29 The Charlotte Observer, 17 April 1927, sec. 2, p. 3.

30 The Charlotte Observer, 9 May 1973, p. 18B.

31 Barry Sanders, A Complex Fate: Gustav Stickley and the Craftsman Movement (New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1996), pp. 4-9; Mary Ann Smith, Gustav Stickley, The Craftsman (New York: Syracuse University Press, 1983), pp. 1-7; Jeff Wilkinson, “Who They Were: Gustav Stickley.” Old-House Journal Vol. XIX No. 4. (July/August 1991), pp. 22, 24.

32 Sanders, Complex Fate, pp. 85-88; Smith, The Craftsman, pp. 45, 54-57, 77.

33 Gustav Stickley, Craftsman Homes (NY: Craftsman Publishing Co., 1909; reprint ed., NY: Dover Publications, Inc., 1979) pp. 52-3.