Click here to view the photo gallery of the Little Rock A.M.E. Zion Church.

This report was written on February 4, 1981.

1. Name and location of the property: The property known as the Little Rock A.M.E. Zion Church is located at 403 N. Myers St. in Charlotte, NC.

2. Name, address, and telephone number of the present owner and occupant of the property:

The present owner of the property is:

City of Charlotte

600 E. Trade St.

Charlotte, N.C. 28202

Telephone: (704) 374-2241

The present occupant of the property is:

Little Rock A.M.E. Zion Church

403 N. Myers St.

Charlotte, N.C. 28202

Telephone: (704) 334-3782

3. Representative photographs of the property: This report contains representative photographs of the property.

4. A map depicting the location of the property: This report contains a map which depicts the location of the property.

5 Current Deed Book Reference to the property: The current deed to this property is recorded in Mecklenburg County Deed Book 4210, page 954. The original deed to this property on behalf of Little Rock A.M.E. Zion Church is recorded in Mecklenburg County Deed Book 60, page 395. The Tax Parcel Number of the property is: 080-104-08.

6. A brief historical sketch of the property:

Little Rock A.M.E. Zion Church was established in the early 1870’s, as the black people of Charlotte were struggling to fashion an identity outside of the shackles of slavery. Its founder was Thomas Henry Lomax (1832-1908), a remarkable and resourceful human being.1 A native of Cumberland County, North Carolina, Lomax had come to Charlotte to advance the interests of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, a denomination which had its roots in the antebellum North but which began to penetrate coastal North Carolina when Union forces occupied Beaufort and New Bern. After the Civil War, A.M.E. Zion preachers moved inland to rally the former slaves to a Christian institution which was entirely devoid of white influence or power.2 The church reached Charlotte about May 1865, when Edward H. Hill arrived and founded Clinton Chapel, the first black church in the city. It stood on S. Mint St. between First and Second Streets.3 Thomas Henry Lomax came to Charlotte about 1873. Six years earlier, in 1867, he had received his license to preach. Initially, he labored in eastern North Carolina, where he demonstrated the administrative skill and adroitness which were to characterize his entire career. It is not surprising, therefore, that Lomax was assigned to Clinton Chapel in Charlotte, an important frontier for the African Methodist Episcopal Church. Between 1873 and 1876, Lomax worked feverishly to build upon the foundation which E. H. Hill and others had started. In addition to increasing the size of Clinton Chapel by approximately seven hundred members, he established a second church in Charlotte, Little Rock A.M.E. Zion Church.4

Little Rock Church originally occupied a parcel on S. Graham St. between Second and Third Streets.5 In 1876, Lomax became a Bishop and journeyed to Canada as a missionary. Although Lomax served the church in several capacities during the decades that followed, he maintained a strong connection with Charlotte and with Piedmont North Carolina. He was instrumental, for example, in having the A.M.E. Zion Publishing House locate in this community. Also, Bishop Lomax was on the committee which selected the site in Salisbury, N.C., for Livingstone College, an A.M.E. Zion institution of higher education. Not surprisingly, he received the Doctor of Divinity Degree from Livingstone.6 Bishop Lomax resided in Charlotte during the final years of his life. He died there on March 31, 1908.7 Indicative of his standing in the community was the fact that the Charlotte Observer commented editorially upon his death. Indeed, the acclaim which he received from the white leadership of the city was almost unknown in those days of intense and prevailing racial segregation. “In the death of T. H. Lomax of this city, the colored race and the community lose a valuable member and the A.M.E. Zion Church a shining light,” the newspaper asserted. “His example and counsels always made for good and by all colors and classes his death is to be regretted.”8

Perhaps some of the esteem which Bishop Lomax enjoyed among his white compatriots was due to his abilities as an entrepreneur. He invested heavily in real estate in Charlotte, especially in Second Ward, and possessed an estate of approximately $70,000 at the time of his death.9 “He had remarkable business talent,” the Charlotte News proclaimed, “and set an example to his people of how power and respect come to a man from thrift and industry.”10 Bishop Lomax is buried in Pinewood Cemetery in Charlotte, N.C.l1 Little Rock A.M.E. Zion Church prospered and flourished in Charlotte. In June 1884, the congregation purchased a lot at N. Myers and E. Seventh Sts. and began the construction of a new house of worship.12 It is reasonable to assume that the people of Little Rock Church abandoned their original building on S. Graham St. and moved to First Ward, because the largest and oldest A.M.E. Zion church in Charlotte, Clinton Chapel, was only about a block away from the initial site.13 By 1889, activities were in full swing at the First Ward location.14 So successful was Little Rock A.M.E. Zion Church in ministering to the black people of the neighborhood that a larger edifice replaced the first building in 1893.15

In order to appreciate and understand the function of the black church in Charlotte in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, one must realize the difficulties which the customs and attitudes, not to mention the legal strictures, of white supremacy and racial segregation placed in the path of black men and women. Imagine, for example, how the black citizens felt when a play entitled “The Nigger” was performed on the stage of the elegant Academy of Music on S. Tryon St.16 Fancy how they reacted emotionally to the announcement that the owners of Lakewood Park, a popular amusement complex, would not extend the fall season for a week in 1910, so the black residents of Charlotte could visit the facility, because the “fear existed that such a course might injure the resort in some manner, or might lesson the prestige.”17 At almost every turn, the black men and women of Charlotte encountered events which threatened their sense of self-esteem. In November 1911, the Board of School Commissioners announced that it was abandoning plans to construct a black school in Third Ward because of the “objections which have been forthcoming from the citizens.”18 In April 1911, black Sunday School teachers were invited to the Mecklenburg County Sunday School Association, but they had to sit in the balcony.19 Within this cultural milieu, the black church served as a haven from the white man; there black men exhorted their congregations to persevere in the face of adversity and scorn. The African Methodist Episcopal Church provided a service whereby congregations could obtain architectural plans from offices in Philadelphia, PA.20

When S. D. Watkins, minister of Little Rock A.M.E. Zion Church from 1900 until 1906, undertook to build more imposing structure for his congregation than the wooden buildings which had housed the people theretofore, he decided to raise the funds to secure an architect.21 W. R. Douglas succeeded Watkins as minister in 1906 and superintended the building program. By May 1908, the plans were drawn and the congregation had raised $2000 in its building fund.22 The building permit was issued in September 1910, and the new church was finished by June 1911. The cost of the new, brick house of worship was $20,000.23 This phenomenal sum of money for a black congregation of that era was raised entirely by the congregation itself. “Built by the subscription of Negroes entirely,” boasted the Greater Charlotte Club, an influential white organization, “this structure is a monument to the thrift and religious inclinations of Charlotte negroes.”24 By pursuing the more difficult and expensive route of securing a local architect, the members of Little Rock A.M.E. Zion Church made a more forthright statement about their standing in the community than would have been the case if they had ordered a standard design from the A.M.E. Zion offices in Philadelphia. The architect of the new edifice was James Mackson McMichael (1870-1944).25 A native of Harrisburg, Pa., McMichael was the architect of several imposing buildings in this community, including the North Carolina Medical College Building, the old First Baptist Church (now Spirit Square), East Avenue Associate Reformed Presbyterian Church, St. John’s Baptist Church, First Associate Reformed Presbyterian Church, and Myers Park Presbyterian Church.26 Unlike these affluent white congregations, however, the people of Little Rock Church had raised the money to hire the leading church architect of Charlotte at great financial sacrifice to themselves.27 The official history of the Little Rock A.M.E. Zion Church reveals that the text for the first sermon in the new building was taken from Nehemiah 4:6: So built we the wall; and all the wall was joined together unto the half thereof; for the people had a mind to work.28

Over the years, Little Rock A.M.E. Zion Church has played a leading role in shaping the destiny of the black community of Charlotte, NC. Happily, the exterior of the building is essentially unchanged from the original. Presently, the congregation is erecting a new sanctuary across Myers St. from the 1910-11 edifice. Hopefully, the old building will survive as a reminder to the contributions of individuals such as Bishop Thomas Henry Lomax, who guided his people toward a new and better tomorrow.

NOTES:

1 Charlotte Observer (April 1, 1908), p. 8.

2 J. W. Hood, One Hundred Years of the African Methodist Episcopal Church (New York: A.M.E. Zion Book Concern, 1895 , pp. 191-195.

3 Ibid., p. 297. Map of Charlotte: F. W. Beers (1877).

4 Charlotte Observer (April 1, 1908), p. 8. William J. Walls, The African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church: Reality of the Black Church (Charlotte, NC: A.M.E. Zion Publishing House, 1974), p. 580.

5 Map of Charlotte: F. W. Beers (1877).

6 Charlotte Observer (April 1, 1908), p. 8.

7 Ibid.

8 Charlotte Observer (April 2, 1908), p. 4.

9 Charlotte Observer (April 1, 1908) , p. 8.

10 Charlotte News (April 1, 1908), p. 9.

11 Charlotte Observer (April 1, 1908), p. 8.

12 Mecklenburg County Deed Book 60, p. 395.

13 Map of Charlotte: F. W. Beers (1877).

14 John Hirst and Dudley G. Stebbins, eds., Hirst’s Directory of Charlotte (Charlotte: Hirst Printing and Publishing House, 1889), p. 35.

15 Mecklenburg County Deed Book 91, p. 366.

16 Charlotte News (January 6, 1911), p. 9.

17 Charlotte Evening Chronicle (September 21, 1910), p. 6.

18 Charlotte Observer (November 10, 1911), p. 6.

19 Charlotte Observer (April 21, 1911), p. 5.

20 Star of Zion (September 7, 1911), p. 3.

21 Official Journal of the Twenty-Third Quadrennial Session of the General Conference of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, pp. 149-150. The Journal states that the plans were drawn “by one of the leading architects of the city.”

22 Ibid.

23 Charlotte Evening Chronicle (October 29, 1910), p. 9. Mecklenburg County Deed Book 271, p. 648. Official Journal of the Twenty-Fourth Quadrennial Session of the General Conference of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, p. 345. 24. Charlotte: The Hydro-Electric Centre (Charlotte: The Greater Charlotte Club, 1913). This source contains an early photograph of the building.

25 Interview of David S. McMichael by Dr. Dan L. Morrill (January 22, 1981). Mr. McMichael, who lives in Alexandria, Va., has the original drawings of the building.

26 Charlotte News (October 2, 1907), p. 5. Charlotte Observer (October 4, 1944), 2nd. sec., p. 1. Charlotte Evening Chronicle (February 23, 1911), p. 9. 27. Eighty Sixth Anniversary Little Rock A.M.E. Zion Church, p. 6. 28. Ibid.

7. A brief architectural description of the property: This report contains a description prepared by Jack O. Boyte, A.I.A.

8. Documentation of why and in what ways the property meets the criteria set forth in N.C.G.S. 160A-399.4:

a. Special significance in terms of its history, architecture, and/or cultural importance: The Commission judges that the property known as the Little Rock A.M.E. Zion Church does possess special significance in terms of Charlotte-Mecklenburg. The Commission bases its judgment on the following considerations: 1) the building was designed by J. M. McMichael, an architect of local and regional importance; 2) the structure is the only known building which McMichael designed for a black client in Charlotte; 3) the building is the most architecturally sophisticated of the older black churches in Charlotte; 4) the only other historic A.M.E. Zion church building in the center city, Grace A.M.E. Zion Church, has already been designated as “historic property” — Clinton Chapel has moved to a suburban location and the original building is not extant; and 5) Little Rock A.M.E. Zion Church has occupied a place of great importance in the cultural and social life of the black community.

b. Integrity of design, setting, workmanship, materials, feeling and/or association: The Commission judges that the architectural description included in this report demonstrates that the property known as the Little Rock A.M.E. Zion Church meets this criterion.

9. Ad Valorem Tax Appraisal: The Commission is aware that designation would allow the owner to apply annually for an automatic deferral of 50% of the Ad Valorem taxes on all or any portion of the property which becomes “historic property.” The current Ad Valorem tax appraisal of the .357 acres of land is $18,680. The current Ad Valorem tax appraisal of the building is $43,270. The property is exempted from the payment of Ad Valorem taxes. The property is zoned B2.

Bibliography

Charlotte Evening Chronicle

Charlotte News

Charlotte Observer

Charlotte: The Hydro-Electric Centre (Charlotte: The Greater Charlotte Club, 1913).

Eighty Sixth Anniversary Little Rock A.M.E. Zion Church.

John Hirst and Dudley G. Stebbins, eds., Hirst’s Directory of Charlotte (Charlotte: Hirst Printing and Publishing House, 1889).

J. W. Hood, One Hundred Years of the African Methodist Episcopal Church (New York: A.M.E. Zion Book Concern, 1895) .

Interview of David S. McMichael by Dr. Dan L. Morrill (January 22, 1981).

Map of Charlotte: F. W. Beers (1877).

Official Journal of the Twenty-Third Quadrennial Session of the General Conference of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church.

Records of the Mecklenburg County Register of Deeds Office.

Records of the Mecklenburg County Tax Office.

Star of Zion.

William J. Walls, The African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church: Reality of the Black Church (Charlotte, N.C.: A.M.E. Zion Publishing House, 1974).

Date of Preparation of this Report: February 4, 1981.

Prepared by: Dr. Dan L. Morrill, Director

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Properties Commission

3500 Shamrock Dr.

Charlotte, N.C. 28215

Telephone (704) 332-2726

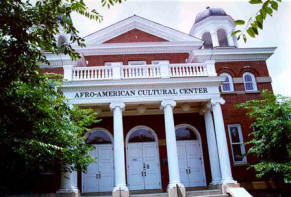

The Little Rock AME Zion Church building is a striking medley of turn-of-the-century revival architectural styles. Romanesque arches combine with neo-colonial trim details and domed bell towers to create a unique and handsome church building, a building which has enriched Charlotte’s First Ward community for nearly three quarters of a century. Its hillside site is visible from several adjoining neighborhoods, and the church is firmly implanted in early memories not only of First Ward residents, but of many who grew up in Elizabeth, Myers Park or elsewhere in eastern Charlotte. Bordering East Seventh Street where it crosses Myers, the large rectangular red brick structure rises from a half basement some thirty feet to a steep tripped roof. Exterior front and side facades are symmetrical and feature a series of cast stone trimmed window and door openings as well as carefully executed Adamesque wall and roof design elements of wood. The entrance facade has a three bay balconied portico in the center and large square corner stair towers at each side. The front wall of each tower has twin windows on three levels. Basement sash are small square projecting vents with opaque, patterned glass. At the second, or main sanctuary level, tall double hung sash windows are set in masonry openings with lintels of brick jack arches. Shorter double hung mezzanine windows have rounded brick arch openings defined by corbeled brick eyebrows.

At the tower side walls single windows at each level repeat, in a smaller scale, the details of front units. The southern tower touches the Seventh Street sidewalk, and here there is a prominent secondary entrance. Double doors open onto a landing from which stairs rise a half flight to the narthex or drop a half flight to the basement. Clear glass panels fill the upper half of each door and flood the stair with natural light. The entrance opening has a low arched stone head. This arch is a continuation of a stone belt course which bands the entire structure at the main floor level. Soaring high above the corners, twin octagonal bell cupolas complete the tower compositions. With segmented curved roofs which rise steeply to knob finials, the domed roof towers are dominant elements in this eclectic architectural composition. The eight sided belvederes have Palladian arches in each segment with wooden casing, spring blocks and arch keys. Both are open to the weather on all sides, yet only the south tower shelters a bell. Simulated stone entrance stairs matching the front portico in width, begin at the edge of the Myers Street sidewalk and rise a dozen steps to a recessed entrance platform. In each bay tall panelled doors open to a narrow narthex. Over the doors arched transom windows are glazed with lead patterned stained glass. Fluted Ionic columns rest on square brick pedestals at the top of the entrance steps. Above this, the flat portico roof has a broad molded entablature supporting a projecting denticular cornice. The balcony balustrade is segmented to match the three bays of the portico. Solid wood panels occur over each column and slender balusters support a molded intermediate rail.

Set behind the balcony the mezzanine wall has three equally spaced double hung sash windows. Over these windows is a projecting pedemented gable featuring molded raking cornices. The Seventh Street facade, which is repeated on the uphill side of the church, is a lofty wall of red brick laid in running bond. This wall rises more than forty feet from a grass sidewalk strip to a modest projecting cornice where a narrow bed mold with dentils is the only elaboration. At the molded eave line a built in gutter anchors a steeple sloped slate roof. At the main floor level, there is a wide band of simulated stone which circles the entire building perimeter. Below this belt line, five shallow windows with low arched heads are spaced evenly in the basement wall. An exterior basement entrance was inserted in the rearmost window opening in subsequent years. The wall surface above the stone belt course is divided equally by five monumental windows. These tall openings have twin sash lower units with mullion dividers. Above are half circle stain black transoms and brick Romanesque arches. Three large gable vents are centered side by side in both sloping long side roof surfaces. Designed as architectural features, these gables have raking cornices which shelter horizontal wood louvers. Wood surrounds for the triangular louvered vent panels are sawn in two cusp, trefoil, arch forms.

Rear facade details are generally consistent with those found elsewhere. A low-roofed wing extends along the Seventh Street frontage and includes a pastor’s study and choir robe room. Simulated stone steps rise from the sidewalk to a simply detailed secondary entrance at this wing. Centered in the high rear facade is a gable roof where another triangular louvered vent has a trefoil wood surround. Important among the extraordinary features which adorn the exterior of the church is the consistent use of leaded stained glass in the windows. On all four sides numerous and varied glazed openings flood the interior with subdued light warmed by multi-colored glass. Following the basic rectangular exterior building form, the church plan is balanced along a central axis. From the main entrance on Myers Street, one enters a low ceilinged narthex flanked by open stair towers. The inside narthex wall faces the nave with a center window and double doors at each side, all set in arched openings. Rising in five runs from basement to mezzanine levels the tower stairways are bordered by mill crafted balustrades and molded wall panels. Sturdy turned balusters support a heavy molded wooden rail. Large square corner newel posts at each landing have recessed side panels and molded caps.

Designed to focus on a center pulpit platform and raised choir chancel, the vaulted nave retains much of its original classical trim, though the pulpit and pew furnishings have been replaced. Wall and ceiling surfaces are smooth plaster interrupted only by a projecting chair rail which borders the interior at the window sill line and a wide crown mold at the ceiling. Plaster arches divide the nave into equally spaced window bays. The curved ceiling is likewise segmented by lowered plaster arches. At the rear of the nave a sloping gallery opens from above the narthex. Here, on high-stepped platforms, are examples of the original church pews. Fabricated of dark stained pine, the heavy seats are typical turn-of-the-century molded and carved furnishing produced in local planing mills.

A dominant feature in the main auditorium is an array of brass organ pipes set behind the chancel in a shallow plastered alcove. This instrument with its fine old console is a significant element in the preserved interior. The Little Rock Church building is a remarkable reminder of an exuberant expression of faith by the earlier congregations. This intricate old classic is important not only to First Ward but the entire community and should be carefully preserved.